An Invitation to Dream:

Reflecting on the 2025 NPN Partner Meeting

By Eva Martinez

• 11 minute read

In early April of this year, NPN Partners DiverseWorks and MECA co-hosted an NPN Partner Meeting in Houston, Texas, where more than 50 arts presenting organizations from NPN’s national network came together to build relationships, exchange ideas with peers, and discuss how to advance liberation and justice in our organizations, our communities, and beyond. As a first-time attendee and a staff member at DiverseWorks, I was eager to connect, learn, and be in community.

Stanlyn Brevé, Director of National Programs at NPN, opened the gathering by setting the tone and reflecting on this year’s theme: Stormshaping: Adaptation, Resistance, Reimagination. She acknowledged the weight of the current moment: economic uncertainty, ongoing attacks on our freedoms, the rise of fascism, genocide, and systems designed to divide and destabilize us.

But she also issued a powerful call to action. “It’s not about reacting to tornadoes,” she said, “but instead to become the storm.” A storm, she reminded us, has the power to reshape landscapes. Through collective strength, imagination, and solidarity, we can move, protect, and care for one another—not simply to endure, but to reimagine what thriving looks like.

Over the course of two days filled with presentations, breakout sessions, meals, embodiment practices, and storytelling with artists, organizers, cultural strategists, and administrators, I came to understand how necessary it is to nurture visioning in community. In the midst of so much upheaval, this gathering reminded me that care, collaboration, and creativity are essential practices for weathering a storm.

The disconnect between funders, artists, and organizations

The morning’s panel, “State of Emergency / Emergent State,” was facilitated by Anne Ishii (Program Director, United States Artists, and NPN Board Co-Chair). The panelists were: Roya Amirsoleymani (creative producer, curator, writer), Sixto Wagan (Project Director, BIPOC Arts Network and Fund (BANF)), and Cassandra Jones (Interim Executive Director, Faith In Texas).

Anne spoke about the NPN board meeting held the day before, highlighting the growing disconnect between funders, artists, and organizations. She named the competing pressures pulling at each group and asked, “What are we going to do?”

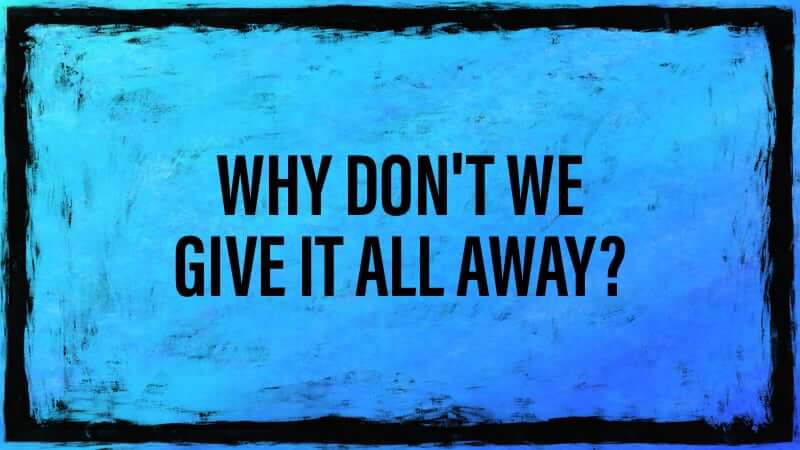

Roya opened by reflecting on how difficult it has been to write amid so much instability. She spoke candidly about leaving her role at Portland Institute for Contemporary Arts (PICA) and transitioning into freelance work. Stepping outside of an institution gave her a better understanding into artistic precarity—unsteady income, deferred dreams, and scrambling for healthcare. Only then did she fully grasp the cost of creating in this system. She offered a sharp critique of organizations and foundations: many are risk-averse and focused on self-preservation. “Why don’t we give it all away?” she asked. It was a call to radically reconsider how we value the present, how we define legacy, and what bold collective action could look like now.

Sixto introduced himself as “the representative of philanthropy,” with a caveat. While he works in funding, he stated that he is a practitioner, not a spokesperson for the sector. Built on tax evasion and structured to perpetuate itself, philanthropy is not designed for liberation. Instead, he called on us to dream of a creative future—one rooted in experimentation, imagination, and resilience. He described BANF as a response to the crises of COVID-19, George Floyd’s murder, and decades of activism. The challenge he posed: If the money disappears, what remains? He urged us to show up at city council meetings, to have hard conversations, and to ask: Where have we failed each other? Systemic change requires collective commitment, not symbolic gestures. His call wasn’t just for inclusion—it was for radical world-building that expands who belongs at the table.

Cassandra followed, grounding her remarks in lived experience. While she works within a faith-based organization, she’s been unaffiliated with formal religion for over two decades. She spoke to a broader definition of faith—one that centers care and safety for all people. As a visual artist, she’s deeply invested in archives, especially the Black family reunion as a site of power and resistance. She emphasized that gathering matters, and that small, embodied practices of resistance and care chip away at structural issues. While art may be labeled as frivolous, she said, it gives us access to our deepest reserves of power. Self-soothing isn’t enough. We need strategy, education, safety, and deeply rooted creative action.

Anne returned to pose a question of possibility, of what might happen if we protected space for the impossible. The phrase “might we” emerged, both as an invitation and an assertion. She reminded us that might, as in possibility, is etymologically tied to power.

The panel closed with a flurry of provocations and reflections:

- Are we asking for what we truly need—or simply what we’ve grown comfortable with?

- Where are we accepting limitations?

- How do we lead with empathy instead of transaction?

- What reality are we working in—and how can we begin to imagine another?

Final thoughts circled back to the matrices of oppression we’re navigating, and to the understanding that we need all kinds of people and strategies to bring forth a new future.

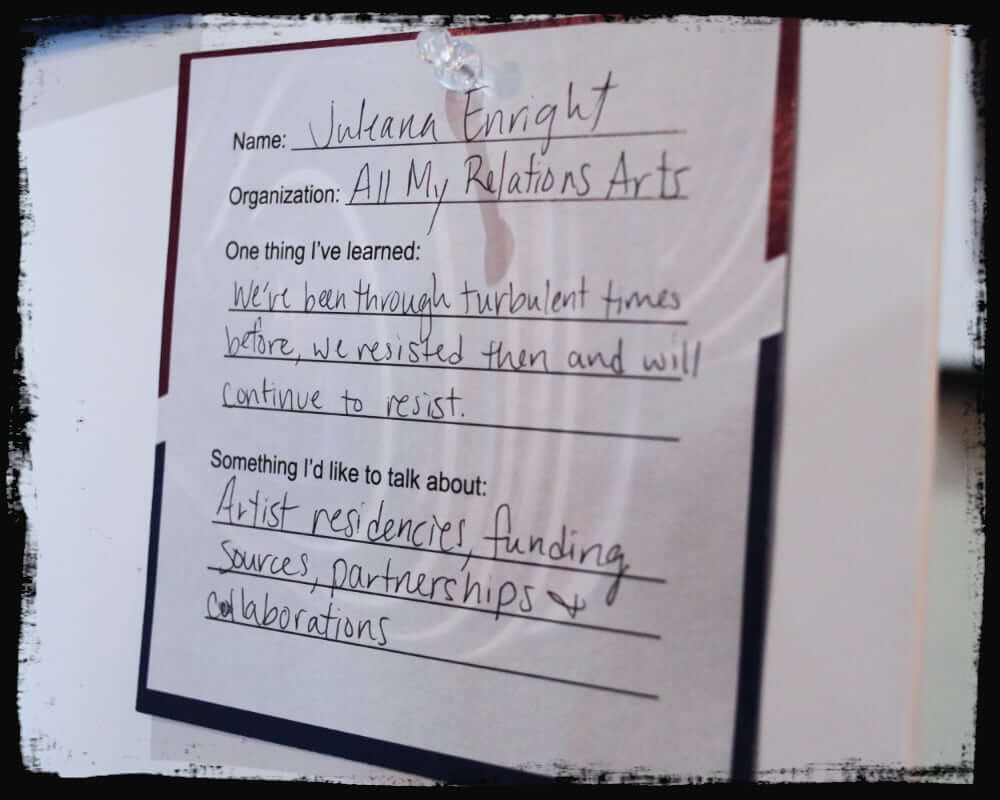

Connecting with dance cards

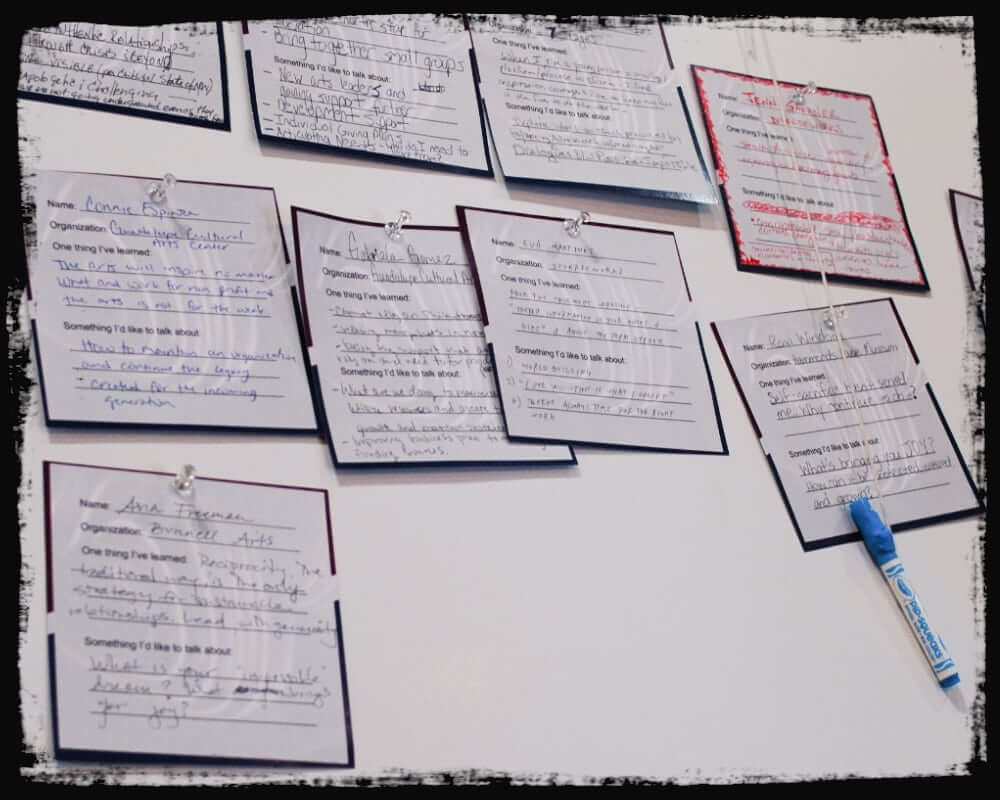

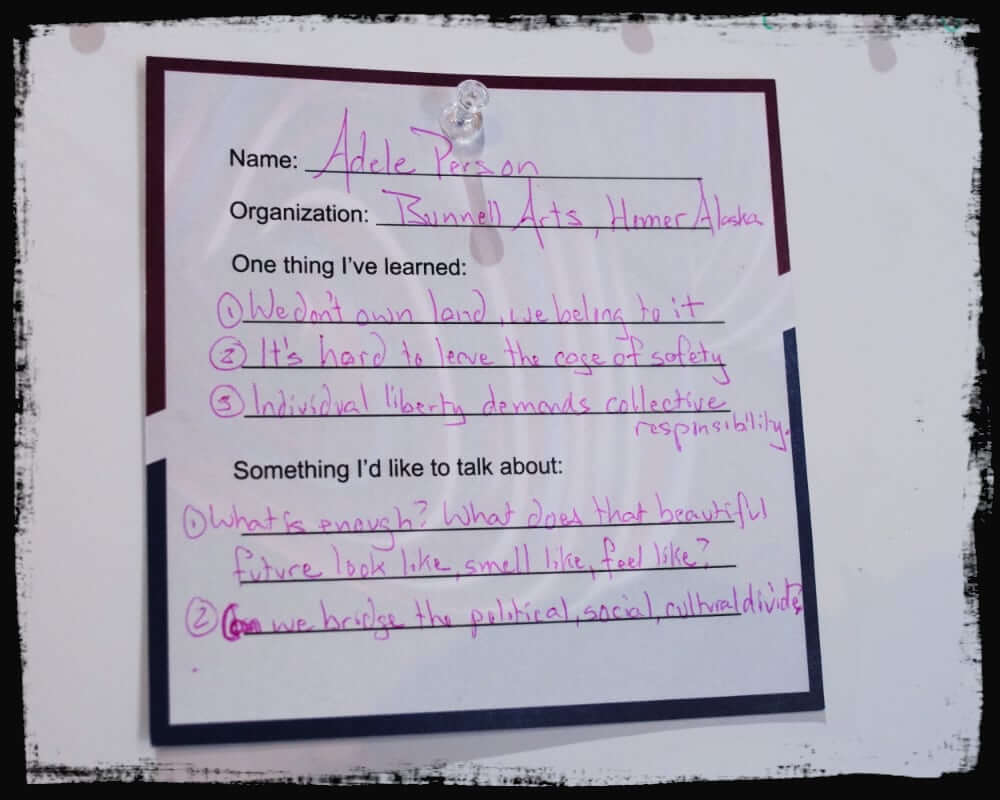

Before lunch, we prepped for the next activity by filling out our “dance cards.” We wrote down a few things we had learned so far, along with topics we wanted to explore more deeply. During lunch, we read through each other’s cards and wrote our names on any that resonated. When we returned, we were paired up based on these shared interests.

My first dance card partner was Eylem Basaldi, a Turkish-born violinist, composer, educator, and booking and tour manager with Art2Action. We began by talking about motivation and how to keep creating over time. After a deep conversation, it seemed to me that she was creating a great deal, especially in collaboration with a broader community of artists. Still, she was questioning whether creating in these tumultuous times was effective, and she felt she was missing a sense of impact. She couldn’t overlook that her community is navigating fear, immigration issues, and uncertainty, and I could feel the weight of that in what she shared.

My second dance card partner was artist and NPN board member Renee Benson. We talked about her work in devised theater and our shared interest in collaboration, especially outside the traditional arts bubble. She talked about wanting to find collaborators in unexpected places. For her, the people with the most powerful stories aren’t always the ones with access to a stage. The art, she said, is in the process of working and creating together.

Later in the day, we had the media share while waiting for buses to take us to the reception. The presentations were diverse, with videos, trailers, humor, a wide range of art forms, and bright personalities. At the reception held in the space outside MECA’s historic Dow School, there was food, drinks, chatter, and two performances. NPN Creation & Development Fund Artist Nejla Yatkin presented an excerpt from her work Ouroboros, followed by a lively set from Mariachis. The evening weather was beautiful, and the energy was open and welcoming.

The power of narrative to create change

We began the second day with conversations around narrative power. Joseph Hall, speaking to the newly formed NPN Network Activation Committee, shared an example from public health. He spoke about how effective narratives around smoking were carefully crafted and widely circulated. The takeaway: How do we, as a network, not just scatter seeds individually, but work together to build shared language and collective power? How do we move something from local to national? There’s power in repetition and even greater power in a chorus of aligned voices.

Asia Freeman then took the mic and reflected on what a privilege it had been to learn with and from this group as an NPN board member, part of the NPN Network Activation Committee, and participant. She spoke about how we gather physically and spatially, and how those structures shape dynamics. Who’s seen as the “teacher”? Who’s the “student”? How does power play out in a room—through race, class, or geography?

Asia reminded us that these ideas are not abstract—they are foundational to NPN’s work. She pointed to the essay “Building the Cultural Power Ecosystem”, which centers on imagination as a form of activism. She said, “Language is critical to giving confidence. NPN is a political instrument.” She concluded that sometimes the work feels slow, stuck, or cyclical—but that’s okay. We’ve been here before and there are people across time and space and in this very room who can support us in our collective work. We don’t do it alone.

“The goal isn’t just resistance—it’s visioning.”

Sage Crump came to the stage to introduce Alexis Flanagan and Tanya Esparza of Collective Acceleration. In conversation, Sage shared her resonance with: “Thriving is everyone having what they need, at the expense of no one.” The goal isn’t just resistance—it’s visioning. It’s not just survival—it’s thriving. She posed a question to the group: “For a network as rich and multifaceted as NPN—multiracial, intergenerational, multisectoral, and geographically dispersed—how do we imagine thriving in a way that isn’t extractive?”

Alexis and Tanya led us in an embodiment practice to ground the visioning session. They asked us to look far out past our own lives to where our descendants are thriving. To trust that there are many paths to get there and that our work today is part of building for them. Tanya introduced us to the teachings of Norma Wong, a Native Hawaiian and Chinese elder who brings spirit, strategy, and embodiment into her work. In many Indigenous traditions, the present is shaped most directly by the seven generations before us. It is our responsibility to shape the seven generations who will follow. Our job is to bring the horizon closer.

Alexis then shared her journey from her backyard in DC to the land in Maryland where Harriet Tubman once stood, where she led 700 people to freedom. Alexis imagined Harriet’s horizon and what dream moved her to take such brave, impossible action. She spoke of a bronze sculpture of Harriet, with a child, Amarinta, at her feet, looking up at her future self, hand raised to the sky, reaching for the North Star. Alexis concluded that Harriet embodied the horizon when she declared, “My people are free.” She left us with this reminder: we are both the dreamers and the dreamed.

We carried that seed into smaller groups to answer: What does it mean to take action from a place where your future descendants already exist? How might that change what you do, how you do it, and why?

We created “horizon stories”—brief, powerful visions of what could be. I loved how this exercise centered reframing—not being overly practical or stuck in current limitations, but imagining what could be possible 150 years from now. It was a powerful invitation to dream.

Closing reflections: collective kindness, collective wisdom

One of the things that struck me throughout the conference was the kindness. There were moments when I felt unsure of myself. But then someone would say something that mirrored exactly what I was feeling, and I didn’t feel so alone. People were tuning into different things, and there was so much collective wisdom in the room.

The Culture Tours held the day before the gathering officially began were profoundly educational and grounding. We visited three historic neighborhoods: Third Ward, Freedman’s Town, and the First Ward/Arts District. Even as a local, I learned so much from the Project Row Houses team, who shared the history of Emancipation Park and Round 58; from a guided tour of Freedman’s Town with Charonda Johnson and Mich Stevenson; and through an opportunity to socialize and wind down hosted by Fresh Arts.

Reflecting on these three days of gathering, I keep returning to this tension: How do we exist in this version of America without becoming complicit in its cruelty? How do we stay aware, but not collapse under the weight of that awareness?

The whole conference reminded me that we’re not meant to know everything alone. We each bring our lens, our attunement. Some people catch what we miss—and that’s the point. We reflect, we share, and that consensus becomes something like truth. In moments of rest, ritual, or storytelling, I noticed how simply being with others, without rushing to solve or produce, opens new ways of creating and understanding.

About Eva Martinez

Eva is an artist and creative strategist focused on promoting diversity in the arts. At DiverseWorks, she leads internal operations, marketing, publicity, and justice initiatives. With experience in digital marketing at several acquired Silicon Valley startups, Eva transitioned into arts administration, bringing her skills to the nonprofit sector. In Spring 2024, she led the launch of DiverseWorks’ new website, strengthening the organization’s digital presence. Since joining DiverseWorks in 2022, she has worked to expand the organization’s social media reach and increase public awareness. Eva holds a BA and MA in Social Psychology from Stanford University (2008) and an MFA in Sculpture from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (2016).