Roberto Bedoya, the Civic We, and the Archipelago of Cultural Policy

By Caitlin Strokosch

• 9 minute read

Roberto Bedoya, cultural strategist, sat down with NPN president and CEO Caitlin Strokosch in October in Chicago to talk about the 20th anniversary of Bedoya’s influential paper on US cultural policy, plans to revisit the work in the coming year, and what Bedoya 3.0 looks like.

Caitlin Strokosch:

You wrote “U.S. Cultural Policy: Its Politics of Participation, Its Creative Potential” for NPN in 2004, and it has become a catalytic text for the cultural policy field over the last two decades. I was rereading it on the plane today and I continue to be moved by how you framed concepts that have shaped our sector and are as relevant today as they were 20 years ago. What are you thinking about these days?

Roberto Bedoya:

I’ve been thinking about relations versus relationships. The Martinitian writer Édouard Glissant in his book Poetics of Relation and his writing talks about the archipelago, how there are all these islands but they’re still connected through relation. I’ve been wondering about the archipelago as a metaphor for cultural policy. I think it allows us to talk outside the frame of capitalism and independent actions. So I want to lean into “relations” and not just “relationships”.

In that paper I refer to political philosopher Chantal Mouffe’s notion of a chain of equivalences as being key to how art service organizations can operate in the sphere of cultural policy. Building up on that notion led me to think about the archipelago as a form of relation that shapes cultural policy and addresses the politic of resources and position that inform hierarchies in the field. This framing appeals to me as it can prompt different ways to make a policy argument.

Caitlin Strokosch:

This is like the third entanglement you talk about in your NPN paper—the private “we” versus the civic “we”. So, maybe “relationships” are about how we engage personally, whereas “relations” is about our civic, communal identity?

Roberto Bedoya:

I think so. This paper is 20 years old and I have not given up on the concept of “we” yet! In this political moment, it’s all about the privatized “we”: what we want, how we benefit, what we think. I’ve written a lot about belonging, relative to the civic we.

When I write about belonging it’s as a sociologist, not a psychologist. A sociologist looks at the social systems that create policies of dis-belonging, like zoning, red-lining, philanthropy, policing, voting rights, etc. But white institutions are using the language of belonging as a marketing strategy for a privatized version of “we” that actually reinforces the apparatus of dis-belonging.

Caitlin Strokosch:

You’re reminding me of the book Elite Capture, which we read as part of our collective learning series at NPN this year. Elite Capture talks about how whiteness co-opts and dominates the concepts of others through exceptionalism and privatization (that’s a huge simplification of a great book!). The privatized we is an entirely different spirit than the civic we.

Roberto Bedoya:

And when you open the door to talk about engagement and justice, whiteness gets mobilized, like the whiteness of dispersing knowledge and expertise, or dominating the narrative. George Lipsitz talks about this in The Possessive Investment in Whiteness, too.

Caitlin Strokosch:

Our sector’s language around whiteness has changed a lot since you wrote this paper, and I’m interested to see how you write about whiteness more explicitly now. You talk a lot about the tension between culture and cultural policy in the paper, too. I know some of that was rooted in the context of the late ‘90s, but you’ve done so much since then to model how we can bridge these two worlds.

Roberto Bedoya:

I like to say that policy is about rules and regulations, and culture is fluid. Cultural policy is about holding these together.

Caitlin Strokosch:

There are so many things in this paper we can revisit.

Roberto Bedoya:

I want to do a rewrite with you and I hope it’s an opportunity for you to claim your story about networks and service organizations. You’ve spent more than 20 years now between NPN and the Artist Communities Alliance, plus your time on the board of Grantmakers in the Arts and the Performing Arts Alliance. You have the wisdom of seeing how this has flowed through intermediaries.

Caitlin Strokosch:

I have to say, there were times in rereading this paper when it made me really sad. There was a fork in the road for advocacy and cultural policy, and folks with money and power chose the path of “measurable outcomes” and commodification of the arts sector.

It’s maddening to consider all the resources that Americans for the Arts and other institutions have thrown almost exclusively into the economic impact argument, and how much of the sector fell in line. We were just on the cusp of that when you wrote this paper.

Roberto Bedoya:

Yeah. But our people are always imagining different frames. Like Emily Johnson’s kinship budget and decolonization rider. You want me to frame this as economics, as contracts? Fine, we’re going to design a way toward justice regardless.

Here’s another idea I’ve been working on, around ROI, inspired by the thinking of Eric Takeshita. With state and local funds in particular, the pressure to demonstrate ROI as return on investment is so profound. What if instead of return-on-investment, we talk about return-on-imagination and influence? Those are my ROIs! My inner chihuahua wants us to be just as aggressive about these ROIs. Americans for the Arts has never had the imagination or courage for this work. But we do!

I think the subject matter of courageous leadership is something we need to write about. I’ve seen you make some courageous decisions at NPN.

Caitlin Strokosch:

Oh, wow. I don’t think of it as courageous, really. We were in a financial crisis and it forced some decisions that we should have made previously. My board chair at the time, Abel Lopez, was an incredible partner to me when I was navigating how to deal with an economic crisis and update our mission to be explicit about racial justice simultaneously. And he said to me one day, “Don’t waste this crisis.”

The necessity of our circumstances provided me with a lot of cover to move other change forward, and many people had my back, including you.

Roberto Bedoya:

Maybe this is a prompt for us, as we think about how we revisit this cultural policy paper this year: Don’t waste the crisis.

Here’s an example: Oakland is really in crisis in a lot of ways, and we keep talking about narrative shift in the midst of that, but policy makers don’t know how to do it. I put out my cultural plan for the city around belonging, and suddenly “belonging” became a sticky word. So, what does crisis allow us to do? Artists are the generators of narrative shift! Patti Smith said, “Outside is the side I take.”

The power of imagination is that it is new, outside any normalized frame. It’s frisky; it brings new knowledge, truth, and emancipations to light. The policy world needs to embrace this “outside-ness”, but cultural policy doesn’t know how to deal with narrative shift because it’s too fluid.

Caitlin Strokosch:

This is where culture is at odds with cultural policy, like you wrote about. And why someone like you is so important, to be a bridge.

Roberto Bedoya:

We’re so lucky to be here with all these new knowledges.

Another question for our discussion is, how do these knowledges enter into the policy frame, and especially philanthropy? Cultural policy stumbles when it just wants to be about culture. It has to be about civic wellbeing. But civic wellbeing isn’t just an arts-and-culture charge. We can model that a bit, but what does civic wellbeing really mean more fully?

Caitlin Strokosch:

You and I were in D.C. earlier this year at the summit hosted by the NEA and the White House, and one of the most powerful speakers about the arts was the Surgeon General. He talked about the value of the arts, and he framed it in tangible ways, but not the kind of tangibles we usually hear about in economic impact studies. He talked about the arts’ benefits to the human condition.

Rereading your paper, I was struck by how our obsession with commodified arts outcomes forced certain kinds of conversations that left little room for the human condition. And our sector became complicit in that.

I’m grateful to be part of different advocacy conversations today focused on wellbeing, and with some greater honesty about how we are complicit in commodification that has deepened inequities and dehumanization in our sector.

Roberto Bedoya:

I think policy is often about constructing complicity. Where’s integrity in cultural policy, if it’s all about power and acquisition, if it’s all about the arts ego-system instead of the eco-system? My colleague Marc Folk’s characterization of our sector’s arts ego system prompts me to think about cultural leadership at this moment in time.

Caitlin Strokosch:

You are a role model for this integrity, Roberto. And you’ve given us all these roadmaps so we—the civic we—can carry on this work. Thank you for this, and for your persistence, and always being willing to help me go deeper and more imaginatively in my practice.

You’re retiring from your job with the City of Oakland this month, but you are such a huge part of the arts-and-culture communities and you’ll always be a part of this sector. So what’s next for you?

Roberto Bedoya:

I’ve been thinking about Bedoya 3.0. I want to write more. I’m considering a rhizomatic method of policy deliverance. I’m excited to revisit this cultural policy paper with you. I want to think more about the archipelago metaphor and… most importantly…

… how we imagine and operatize “networks of care and capacity”. I’ve been lucky to be associated with a national group—we call ourselves Goldenrod—that came together at the beginning of COVID-19. For a few years now, we have been zooming and had a couple of national convenings and have been thinking about the importance of networks that can advance our self-care, care of each other, our field, our civil rights, our democracy, our civic imagination.

Caitlin Strokosch:

I’m excited for Bedoya 3.0. Let’s keep making trouble together.

Roberto Bedoya:

Amen!

Postscript: We conducted this interview in early October, a month before our recent election, which has triggered much reflection on how we move forward as a Civic We: that secular we, that includes people you don’t know. How do we govern amidst the animosity that is at play in civic life? To be explored…

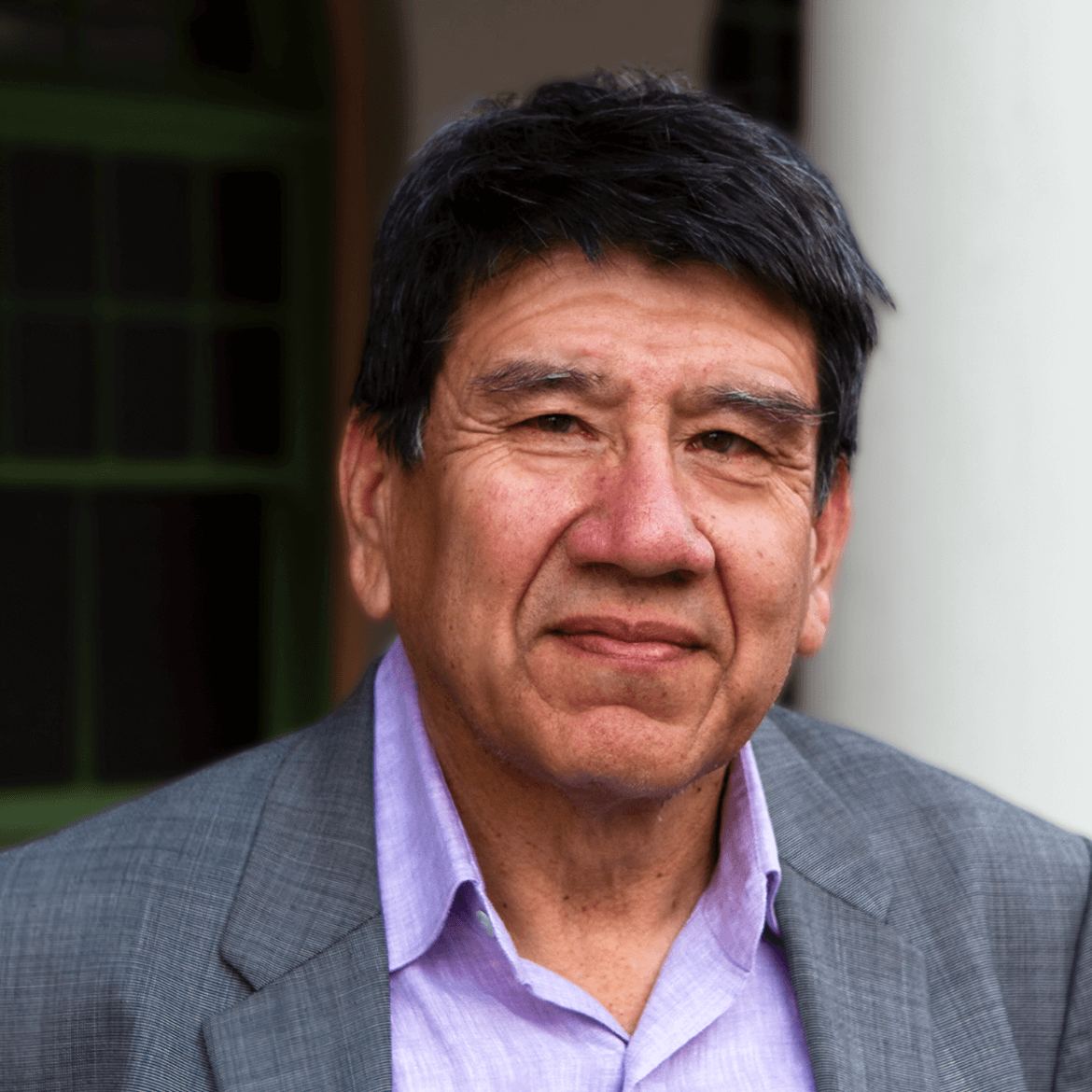

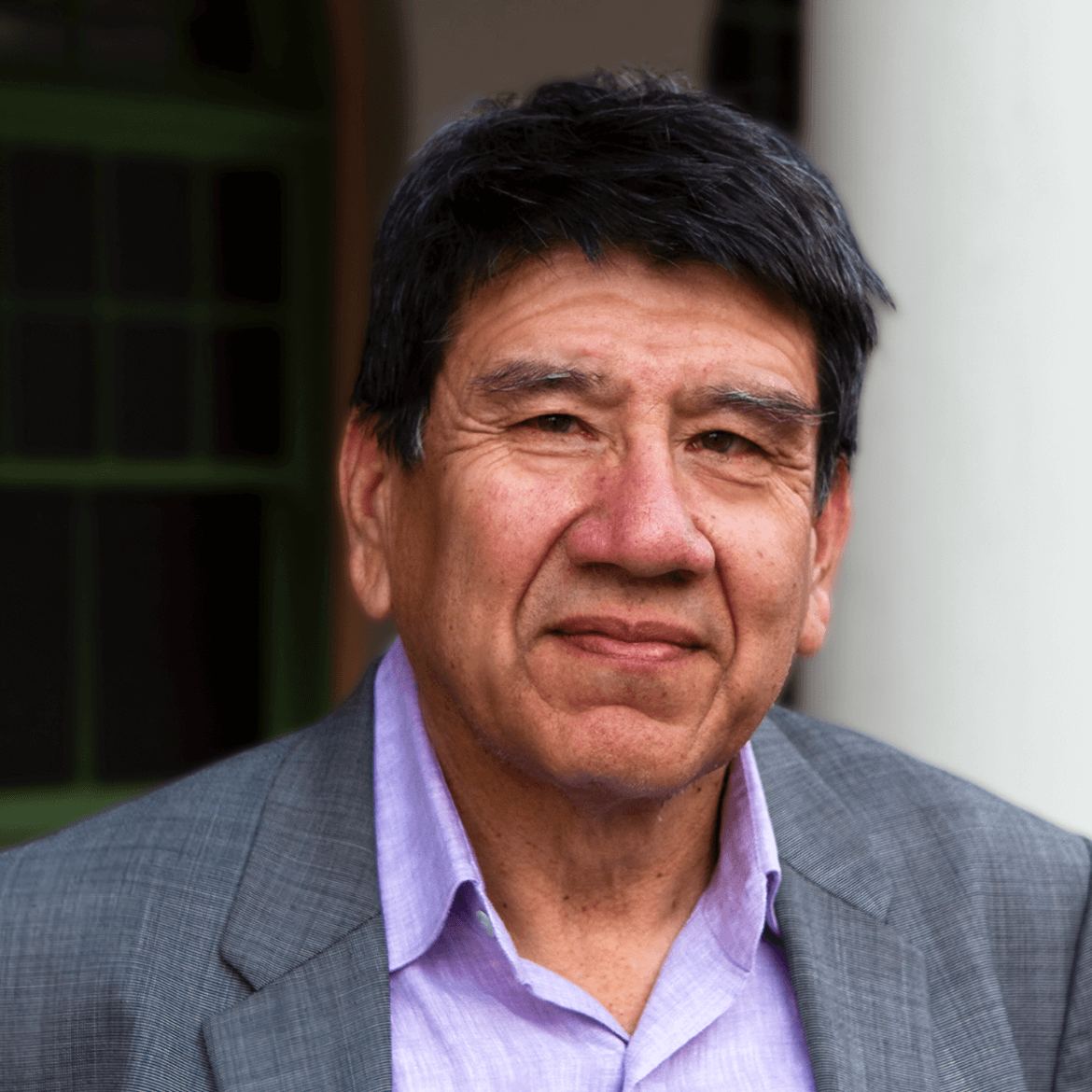

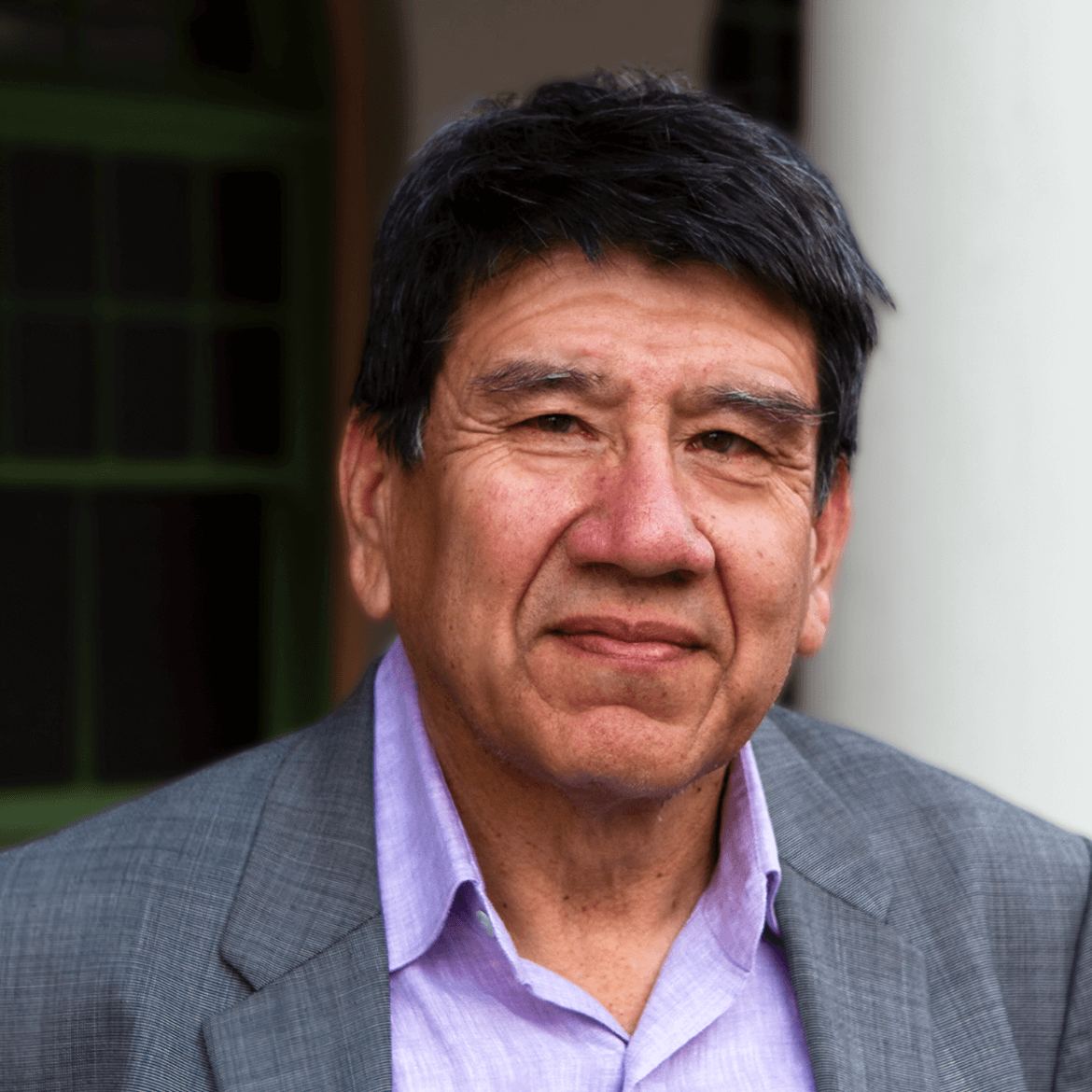

About Roberto Bedoya

Cultural Strategist

Roberto Bedoya retired in October 2024 as Cultural Affairs Manager for the City of Oakland, where he shepherded the City’s Cultural Plan, “Belonging in Oakland“. Throughout his career he has consistently supported artist-centered cultural practices and advocated for expansive definitions of inclusion and belonging in the cultural sector. His essays “Placemaking and the Politics of Belonging and Dis-belonging”, “Spatial Justice: Rasquachification, Race and the City”, and “Poetics and Praxis of a City in Relation” have reframed cultural policy to shed light on exclusionary practices and decision making. He is the recipient of the United States Artists 2021 Berresford Prize given annually to a cultural practitioner who has contributed significantly to the advancement, well-being, and care of artists in society.

About Caitlin Strokosch

President and CEO, NPN

Caitlin Strokosch (she/her) was appointed President and CEO of the National Performance Network in 2016. Most recently, she served the Artist Communities Alliance—an international association of artist residency centers—from 2002 to 2016, where, as Executive Director, she was instrumental in creating the Artist Communities division at the NEA in 2008. She is a frequent speaker and writer on the work of intermediary arts organizations, racial equity, economic justice for artists, and international exchange.