Collect in Power:

Conversations with Artists and Activists Working for Prison Abolition

A reflection by Jo Kreiter

• 9 minute read

Three screens going at once. I am waiting. It’s two in the morning on the day after the presidential election, and I am waiting. The whole of the country—the whole of the world—is waiting. Ballots are being counted and we are waiting. Waiting is something I know well. As a woman with an incarcerated loved one, it’s framed the whole of my life these last several years. I’ve raised my son in a state of waiting.

It’s Thursday now. Still no word. I have a Zoom check-in with my Essie Justice Group sisters. I have worked with this organization of women with incarcerated loved ones since 2017, both as a participant in their Healing to Advocacy training and as an artistic collaborator who has featured the stories of Essie women in my performance The Wait Room. On the Zoom call, we celebrate the criminal justice legislative victories this election has brought in California, most notably the passage of the right to vote for returning citizens. We share anxiety and grief. We share sorrow that so many white women have voted for Trump. And we share certainty that Black women like Stacey Abrams and the women of Essie are the ones creating sustainable change. I share a tidbit I learned from new friends at Voice of the Experienced (VOTE) in New Orleans, a grassroots advocacy group founded and run by formerly incarcerated people: that Tarra Simmons is the first person in the state of Washington to win a state Senate race despite a felony conviction. My Essie sisters celebrate this win with me. It’s a small kernel of political truth I would not have known about had it not been for my residency with the Contemporary Arts Center (CAC) in New Orleans.

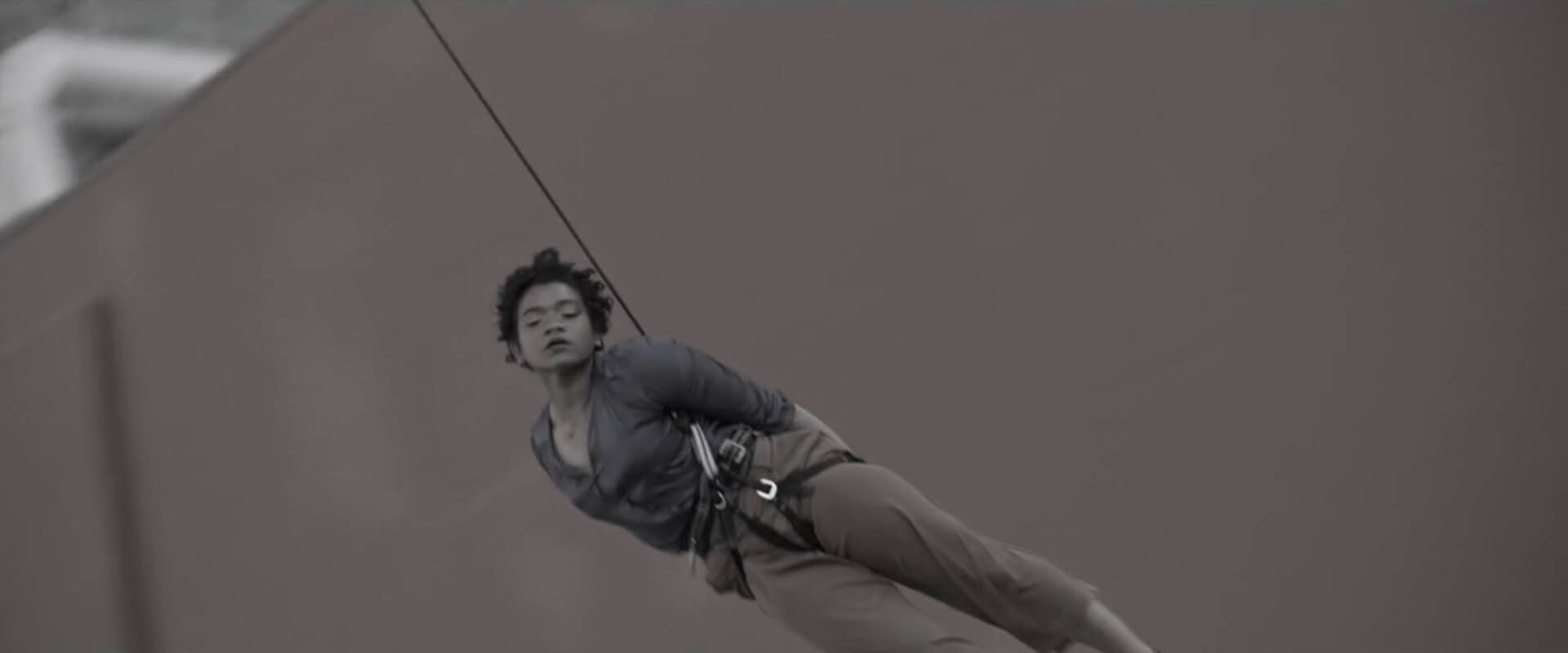

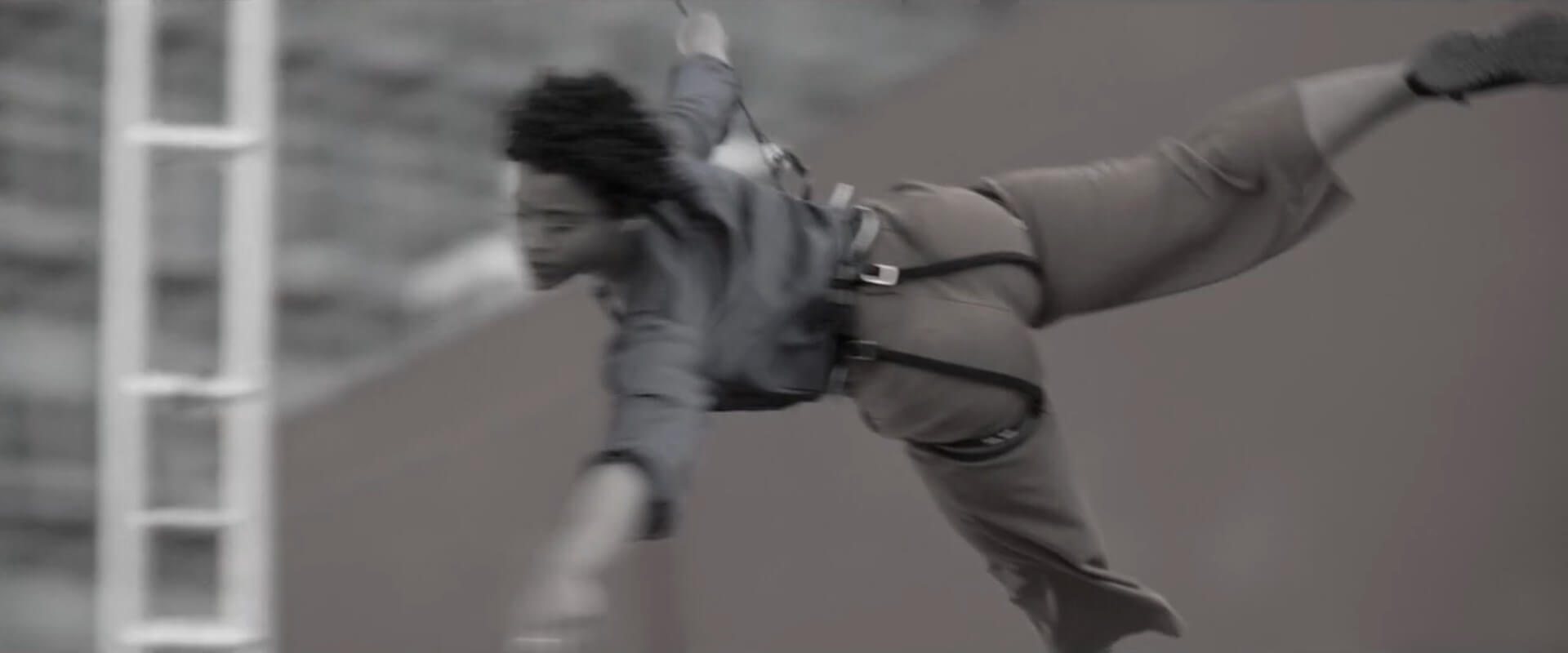

The Wait Room by Flyaway Productions. Full credits available on Vimeo.

In the fall of 2020, the necessities of COVID-19 shifted my relationship with the CAC. Instead of in-person visits and teaching, we developed Inter(SECTOR), a series of online conversations with influential artists and activists in New Orleans. This work is being done as a lead up to Gender (in)Justice, a four-month CAC program featuring art that embraces prison abolition. The program will take place throughout 2021 and includes The Wait Room, created in 2019 with my company, Flyaway Productions. My interactions with artists and activists in New Orleans continue to live with me.

Theater artist Kathy Randels, the community liaison for the project, takes me to the office of VOTE on my first visit to New Orleans. Kathy embodies relentless positivity. Her contagious hope comes into a room with her and makes itself at home. She soaks love into every meeting we are in. Every room needs a Kathy—especially every creative space that wants justice to come in.

Kathy takes me to meet the assistant warden at the Louisiana Correctional Institute for Women (LCIW). That’s a fancy name for a tough prison. We drive down a long, slow road to get there. The drive feels so much like the drive I’ve had to do in Texas to visit my partner. So many prisons are buried down these long roads, lined by tall green trees, whispering. Isolation and shame live down these hushed roads.

Stills from The Wait Room by Flyaway Productions.

We sit with the warden for an hour or so, trying to talk her into hosting The Wait Room inside the prison. It is a long shot. Because Kathy runs the LCIW Drama Club here, we think it is worth the ask. It’s uncomfortable to look into her eyes and then look up on the wall above her and see the heads of dead deer stacked in a neat row as decoration. Or moose. I can’t bear to look up long enough to take in which dead animals are up there.

What comes out of the conversation is illuminating. I’ve learned from Bay Area prison abolitionists that language matters. That the words “inmate” and “offender” allow for a dehumanization of the person who has caused harm. The warden keeps referring to the women of LCIW as “offenders.” In every response, I flip the language to “person who is incarcerated.” Kathy notices. There seems to be so little room in prison, or even once you return, to reclaim your humanity. Your everyday-ness. To accept that you did something wrong, but you still brush your teeth and draw pictures for your child and long for comfortable shoes and a pretty blue coat.

Later on in the residency, I share airtime with Kathy and Ausettua AmorAmenkum, co-directors of the Graduates and the LCIW drama club, which they’ve led together since 1996. These women astound me with the depth of their commitment and artistry. The Graduates grew out of that program, for women in reentry. Because my partner was in prison for many years, I refuse to go back into the prisons as an artist, which has proven to be both a limitation and a strength. To be a woman with an incarcerated loved one is to be in inevitable collusion with the very system that is dragging your family down. You go visit. You put money on the books. You interact with the COs on visiting day. You smile politely when the police state shows up in your living room once a month via the probation process. These small collusions chip away at your sense of self. They make you a collaborator. So I draw a line at going back into the prisons. But Kathy and Ausettua are not burdened by prison culture in the same way. They bring freedom with them via dance, ritual, and theater. They break down walls by gathering women into their power, even though their physical space is caged.

Stills from The Wait Room by Flyaway Productions.

Through Kathy I also meet Ivy Mathis, a former member of the LCIW Drama Club. When she got out of prison, Ivy turned her energies toward political work, as a way to honor the friends she left behind upon her release. During our Inter[SECTOR] conversation, Ivy and I spoke of her organizing with the Baton Rouge Chapter of VOTE. We talk about captivity and freedom, and I muse on the power of art to tell our stories in different ways than in data, facts, and the news. “Dance allows you to remove yourself from reality, yet stay in touch with reality,” she responds. “It’s a form of expression that you really can’t say; you let your body tell it. It just draws people in. Whatever your story is, whatever your experience is, you do that with your body and it is received.” She understands the power of being witnessed. “Art allows me to be with the deep core of individuals who are watching, whether they view through hurting eyes or heavy eyes or inspired eyes.” Ivy continues to work with the Graduates. She embodies the best hope I know—an artist who has transcended bitterness and puts her energy full tilt into the daily and often tedious work of conjuring change.

Sibil Fox and Robert Richardson—known as Fox and Rob—created the Participatory Defense Movement New Orleans. Fox and Rob teach justice-involved families to “use awareness as the greatest form of defense.” Fox asserts, “We teach families how to fight for themselves against a system that is racially biased and unjust.” She has a feminist perspective on incarceration in common with Essie: “The whole bulk of mass incarceration, it lays on the back of the Black woman. When we empower these women to be soldiers, they teach other people to fight as well.” Fox and Rob and Felicia Gomez of Essie in California allow me to moderate their virtual conversation as part of Inter(SECTOR). Both groups honor the power of women with incarcerated loved ones and center those impacted by incarceration as the people we should look to for undoing prison systems. Disparate geographies and the incessant demands of the work can isolate, and I am honored to create the space for these two activist groups to meet and compare strategies.

Months after our virtual conversation, one of my Essie sisters puts out a call for support for her partner, who is facing his fourth attempt to get out of prison via a parole board hearing. He’s been inside for 21 years. I put her in touch with Fox via email. Fox worked for 21 years to get her partner Rob free. She knows the stamina it takes, the grating politeness with which you have to communicate with the parole board administrators, the daily tax on your family for being a woman in love.

Stills from The Wait Room by Flyaway Productions.

The first time I met Maryam Henderson-Uloho, she made me cry. With the aim of “reversing the trauma of incarceration,” Maryam founded SistersHearts Thrift Store and SisterHearts Exit ReEntry Organization (SHERO), based in part on her own experiences in the system. Maryam wastes no time. During our first conversation in her shop, she speaks of the likelihood that my partner was raped in prison, adding that it’s something he would never tell me about. While I contest her assertion, I appreciate her penchant for blunt truths. Her truths are the living wisdom of a Black woman in America, still resisting the legacies of slavery. “Rehabilitation is something that takes place in the mind,” she says. “In prison, we are dehumanized, demoralized, and desensitized. As a result, you have institutionalized people coming out into the society, and we have no way of rehumanizing ourselves, simply because we don’t know.”

With Zoe Boekbinder, composer and co-founder of the Prison Music Project, I talk in depth about how we as white people can fight the anti-Blackness at the core of the prison-industrial complex. We speak of the need for endurance and sustaining our commitment to abolition work. We speak of leveraging our privilege when invited to by folks who are currently incarcerated. One of her collaborators, Bruce “Sincere” Dixon, called us up mid-interview. The call was unplanned, and hearing from Bruce is a starburst of unexpected joy. Not enough people who live in prisons get to be heard on internet broadcasts. So often the phones don’t work or your unit goes on lockdown. And the COVID pandemic has made connections with incarcerated artists that much more difficult.

But Bruce finds us on that particular Thursday and gives us a reason to believe in decarceration. “In prison right now it’s a lot of beautiful minds, as far as music, poetry, writing,” he says. “If they can just get a second chance, get their voices heard from behind these walls . . . When people realize the talents they got through the arts can change lives and motivate people and help people, they will want to do that more than anything else . . . The arts are really important to rehabilitation.”

As the divisions of America chug on and white advantage reveals itself as a deeply entrenched American preference, performances of The Wait Room loom. In September we will arrive at Algiers Point—the first landing and holding area for enslaved Africans in New Orleans, chosen to connect historical American slavery to current-day mass incarceration. We will gather folks together and celebrate the anger and joy that anchor together communities of justice-involved people. Across the states of California and New Orleans, we will collect in power and resist through the mingling of dance, flight, music, and the rituals of live performance.

Thanks to CAC staff Laurie Uprichard, Kaisas Peguero, Laura Tennyson, Ryan Kreiser, and George Scheer. And special thanks to the NPN’s Community Fund for making these conversations possible.

About Jo Kreiter

Jo Kreiter is a San Francisco-based choreographer and site artist with a background in political science. Through dance she engages imagination, physical innovation and the political conflicts we live within. She founded Flyaway Productions in 1996. The company uses the artistry of spinning, flying, and exquisite suspension to engage political issues and to articulate the experiences of unseen women.