On Efficacy and the Institution

By Ann Glaviano

• 10 minute read

Eleven years ago, I returned to the church where I was baptized. It wasn’t a church anymore; it was being briefly used as an unauthorized performance space. Possibly the new owner got a one-off event permit from the city—I can’t remember. The Archdiocese of New Orleans had opted to sell off the property after Katrina rather than repair it. This was a church in the Lower Ninth Ward, whose parishioners included folks in the neighboring community of Arabi, in St. Bernard. The church got about three and a half feet of water.

I usually ate Sunday lunch with my family in Arabi, in a house that got nine feet of water—a house that my family rebuilt. At lunch, my aunts and uncles often spoke heatedly of this decision by the Archdiocese to sell the church. Most of them had gone to the church’s accompanying grammar school. My mom and her siblings had been married in that church. So had my grandparents. And my great-grandparents. Everyone in the family had been baptized there.

By the time Katrina hit, I’d long since given up on Catholicism, Christianity, and all of organized religion. I did appreciate faith—something I’d never had. And I did not think it was silly for my family to care about this church building, a nexus of our lives.

But I did not understand their anger. One thing I learned in Catholic school was that the material resources of the church ultimately belong to the Church. To Rome. Like any franchise, the Church must efficiently and effectively manage its resources, reallocate its investments where there is greater need or demand or opportunity. I had seen it play out my whole life. Priests, buildings, schools, parishes: the Church giveth, and the Church taketh away.

It was a mild October evening. The doors of the old church—which for nearly a decade had been secured with a thick chain lock—were wide open. Hip young white art aficionados streamed in, eager to see a nationally renowned indie guitarist play an avant-garde set in this raw venue in the Lower 9.

I too was eager to see the set, and the space. But it all went sideways for me as I made my way up the church steps.

The pews had been taken out. The stained glass windows were gone, and the statues.

But that wasn’t the problem. It was the walls. The ceiling, the floor. They were all intact. Even the light fixtures. The lights were on, and the light fixtures were intact, and the light fixtures were, for some reason, what really killed me.

I’m not sure what exactly I’d been expecting to see. I think I must have been expecting cataclysm. And what I saw instead were the same light fixtures that had been in place since long before I was born.

I found myself suddenly enraged.

An audience member next to me, looking around the space, wondered aloud, “Why isn’t this a church anymore?”

Later, my aunt would explain to me: her father had changed the lightbulbs in that church. It was their church. This is not a sentimental assertion. With their own money, in 1857, parishioners built it. With their own money, they maintained it. In 2002, in preparation for the church’s 150th anniversary, parishioners completed a $2.1 million capital campaign, which was invested in a full restoration of the building. In 2005, Katrina hit—after which the Archdiocese shuttered the church, and in 2008, sold it off.

A damaged property, a dwindling parish, responsible fiscal management.

Over Sunday lunch in Arabi, my family spoke of it as theft.

“Did they have the building underinsured?” my aunt hissed. “What did they do with the money?”

That night in October, in the deconsecrated space, the musicians commenced their set, and I conceived my next show. We would mark off sites within the empty building and name for the audience what it had once held. The baptismal font. The choir loft. The crying room. And not just physical space—the church was also a container for narrative space. Here is where my dad fainted, on the altar at his wedding. In each site we would perform a dance. In this way, we would reconstruct the church. When the dance was done, the church would disappear again.

I entered the devising process for this show with a question:

What happens when an institution persuades a community to invest—materially and spiritually—in a narrative about identity, security, right action—persuades the community to centralize the institution in their lives, to rely on the institution’s deep governance to sustain them from cradle to grave to beyond the grave—and then that institution unceremoniously pulls out?

The people believed. They bought in, dearly. Now the institution is gone. And they’ve taken the center with them.

What happens? What’s left?

In one of my early encounters with contact improv, my teacher offered a score by Steve Paxton called “the small dance.” The score: Stand still. Notice, in the absence of voluntary movement, what remains.

I stood in place for thirty minutes, feeling the muscles in my legs subtly engaging and releasing. These muscles were responding to tiny shifts in the position of my body mass. I was reminded of the way babies look when they’re learning to sit up, tilting and jolting like an airplane passenger who has just fallen asleep. A baby’s fine motor control is limited, and so the muscular actions required to stay upright are obvious. I am forty-one years old, and the mechanisms that enable me to stay upright operate so smoothly that it creates the illusion I am standing still. We call this balance.

Stillness is a fiction.

Balance is a fiction.

What the small dance revealed to me is that all I am ever doing is falling and recovering.

While building the show, I decided on a whim to go back to Genesis, the beginning of everything, and refresh my memory of what the book said about water. I’d read the story many times in Catholic school. But what I found when I returned to the text made me feel as though I’d never read it before in my entire life.

I was taking it sentence by sentence, comparing different Bible versions, ultimately favoring one from 1862 called Young’s Literal Translation. I relinquished everything I’d been taught, by faith and by culture, about how the story goes and what the story means. I tried to consider only what was on the page. I looked at the characters, their actions, their apparent motives, the consequences, the implications of those consequences.

What I found was a strange and beautiful and surprising account of where we come from and who we are.

I have gone back to that book over and over again as a reference point, in both artistic process and spiritual crisis. As befits a woman in her early forties, I have started to wonder: what exactly are we even doing here?

After extensive research, I suspect that what we are doing is the small dance.

So. Here we are, in 2025, meditating on agency and upheaval, on bottom lines and broken promises, sea change and the ephemeral. And I return once more to the book of Genesis, the origin story—what we refer to as the fall.

Efficacy. From the Latin efficācia (“powerful, efficient”).

Efficacy is the ability to produce a desired result.

What is the first desire?

It belongs to God, is never named, and is located somewhere in the emptiness that precedes the first story.

The initial creative thrust—heavens, earth, darkness upon the face of the deep, light, day, night, and so on—is the manifestation of this desire. I see evidence of desire, too, in God’s assessment of his creation, his question of satisfaction (he saw that it was good).

Adam likewise seeks satisfaction in a helpmeet—an equal companion. God is busily forming beasts and fowl from the ground and bringing them to the man to see if they are adequate. But Adam finds none suitable. His desire for a true counterpart is what finally inspires God to remove Adam’s rib and use it to make Eve.

Then the story really gets rolling.

In the garden, the plot turns on Eve’s desire.

In Eden, and east of Eden, no one is exempt from desire. Desire is what makes life force visible. Desire is what drives creation. And desire has no end.

I find it difficult to accept the enduring nature of my desire. I have been taught to problematize it. Surely it is a problem to never be finally satisfied, to always want more and better: skill, knowledge, love, money, power, health, peace. Is desire not the root of physical addiction, spiritual rot, all human suffering?

When I asked you to name the first desire, did you think that the answer was Eve’s?

In Eden, and east of Eden, desire exposes you to frustration and disappointment.

In Eden, and east of Eden, systems grow until they break.

Like everything growing on our planet, I am shaped by my desires. I can see how they determine my choices, even the mundane ones. What time I go to bed, and where I show up in the morning, and who I turn to in a crisis, and how I fix my hair. These choices facilitate movement in the direction of my desire, and I become the person I become as a result of navigating this path, and the devising process continues.

Efficacy is the endowment of all creators. And we are all creators.

To commit to my desiring is to commit to transformation.

And another word for “shaped” is “warped.”

In pursuit of satisfaction, the infinite game of incarnation, I occasionally remember to ask:

Do I like how I am being shaped by this desire?

Do I like how I am showing up in this shape?

At a crucial point in the story, Eve has received contradictory information from two sources. One source says if she eats fruit from a certain tree, she will die that day. The other says she won’t die, her eyes will be opened, and she will be like God, knowing good and evil.

Then—and this language is consistent across translations—the narrator spells out what it means to be opened in this way: Eve saw that the tree was to be desired to make one wise.

Based on the information available to her, Eve’s got fifty-fifty odds of dying if she eats the fruit. And she eats it anyway. The narrator makes it explicit. She stakes her life for wisdom.

What is wisdom? Wisdom is the gift bestowed upon the dancer. Fall, recover, fall, recover. Wisdom is knowledge that can only be born from pain.

The guy who’d bought the church property let me tour and document the space. I invited former parishioners to come with me, and then facilitated a focus group to collect as many stories from them as I could. I attended one of the grammar school class reunions, during which I was told, repeatedly, that the stained glass windows had been moved to a newly built church across Lake Pontchartrain, and that the windows had been installed “in their original order.” The emphasis on this detail touched me. It felt like a point of significance that could only really land if you’d put in the hours as a kid in that church, spacing out during Mass, eyes drifting to the artwork. I drove to the Northshore to see the windows. I made a dance for the show called “The Stained Glass Windows In Their Original Order.”

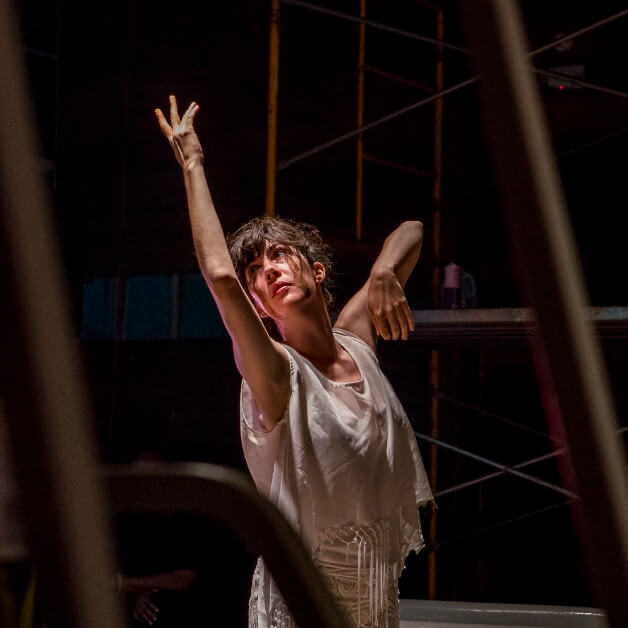

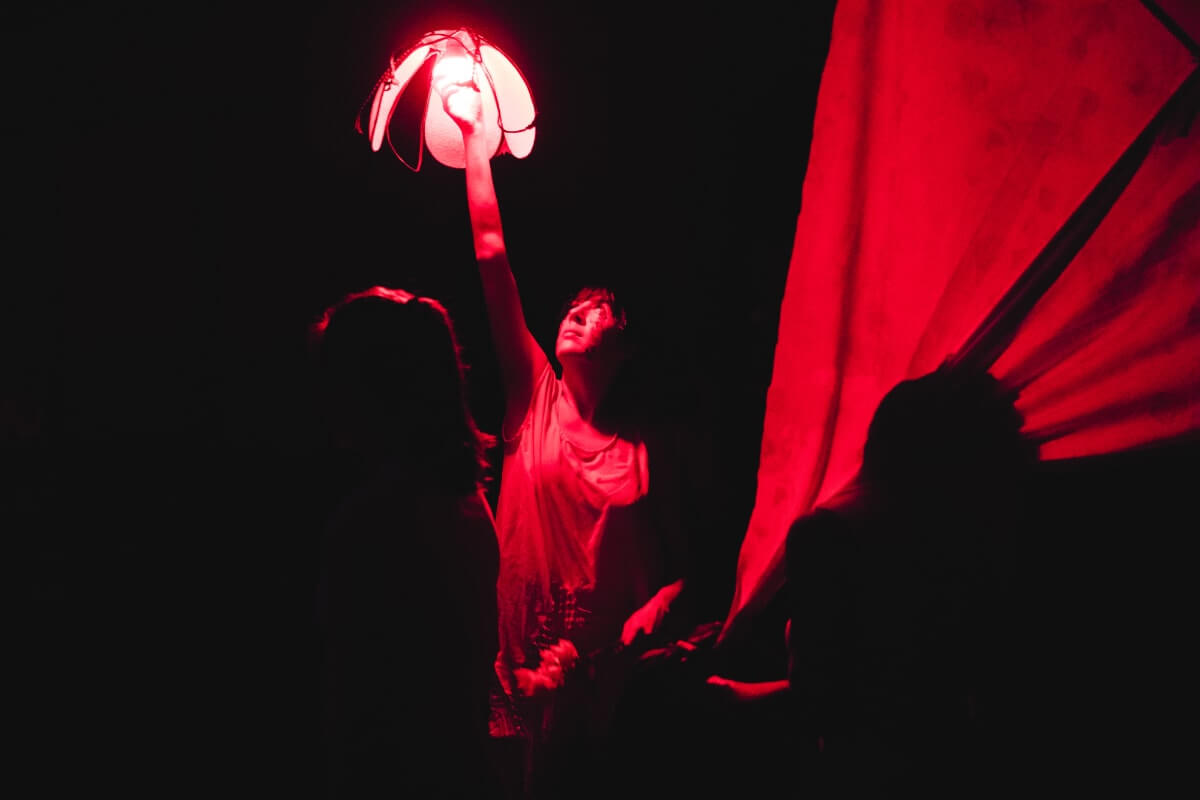

I built and performed the show in a DIY art venue called Art Klub. I built and performed it again in a DIY art venue called Happyland, and a DIY art venue called Minicine. For the soundscape, a friend I’d had since the first month of ninth grade at our all-girls’ Catholic high school composed and performed an electronic Latin Mass. It was an ensemble show. All the performers were women.

The piece opens with a guided tour of the space. I describe the $2.1 million renovation. I point out the steeple and explain that it had blown off in Katrina. I am gesturing to some metal scaffolding, inside a derelict building that used to be a single-screen movie theater and today lacks climate control or even fully intact walls. The scaffolding doesn’t remotely look like a steeple. Our “choir loft” is a raised platform. Our “baptismal font” is a galvanized steel tub from a hardware store. We climb the scaffolding. We dance on the platform. We douse ourselves in the steel tub. After the performance, audience members say to me, “I didn’t realize this used to be a church!”

Look at the power of human imagination, of co-constructed narrative, our capacity to build a world.

If we performed it as I had originally envisioned, in the deconsecrated building, the audience would see us activating the empty space of the old structure. Instead, as we perform it, the players and the audience create the whole church together.

At the end of the show, we dismantle what we’ve made. The dances, of course, have already vanished. We exit; we leave the audience behind. Other than the audience, the space is empty again. Church bells ring and fade.

What happens to a community abandoned by the institution on which it has been taught to depend? What’s left?

To tell you the truth, I never expected an answer to my question. The question was just a way to get my project started. To focus the work, to channel my anger.

I got my answer, though.

What’s left is the people.

About Ann Glaviano

Ann Glaviano is an independent artist and born-and-raised New Orleanian. She received an MFA in fiction and interdisciplinary minor in dance from Ohio State. Her writing has been published in Tin House, Slate, Best American Short Stories, and elsewhere. Since 2013 she’s directed the New Orleans-based performance project Known Mass, aesthetically and ethically motivated by devised theatre and DIY punk traditions, producing collaborative projects with local dancers, musicians, photographers, filmmakers, and visual artists.

Ann is currently working on a book project called The Small Dance and an evening-length solo called an animal dance. This work has been supported by Ann’s colleagues in the re:FRAME choreographic collective, along with residencies at Basin Arts and MANCC, and funding from the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Foundation, the National Performance Network, a Platforms grant from Antenna Gallery, and a finalist award from the National Dance Project. These competitive awards and stipends have totaled $16,210 over six years of artistic labor, during which time Ann produced and performed eight drafts of her solo work-in-progress. In 2024, the local arts institution contracted to premiere her solo reneged on the contract.

Meanwhile, Ann continues to seek “encouragement” — in the form of funding, residencies, interesting conversations, or whatever other shape you might have to offer it — for these projects, which are considerations of dread, catastrophe, grace, and community informed by her experience living in the Gulf South. If you want to connect with Ann, contact her at .

Photo credit:

Known Mass No. 3, “St. Maurice.” Ann Glaviano. Shreveport, 2019. Photo: Shannon Palmer.