The Earth has recently entered the Anthropocene, the current geologic epoch.

It is defined by human impacts being the greatest shaping factor on the planet, equaling those of ice ages, meteorite strikes, and continental shifts. The Anthropocene acknowledges the global distribution of pollution and plastics and the atmospheric masses of carbon and methane that result from industrial manufacturing and farming, as well as the rise of human-caused environmental disasters including forest fires, oil spills, and nuclear contaminations. The Anthropocene is a time of rapid change and is accompanied by the need for resilience and innovation.

This presentation was originally developed for the “Art in the Anthropocene” episode of the podcast Inspiration and Adaptation, released in August 2020 and produced by the Bunnell Street Arts Center in Homer, Alaska.

Nina Elder creates projects that reveal humanity’s dependence on and interruption of the natural world. With a focus on changing cultures and ecologies, Nina advocates for collaboration, fostering relationships between institutions, artists, scientists, and communities.

With NPN’s support, Nina is developing It Will Not Be The Same, But It Might Be Beautiful. This multimedia project poetically explores how humans are implicated in the Anthropocene and are also tasked with moving towards a more holistic future. Through video installation and large-scale drawing, this investigation of change focuses on objects that have been exhausted by use and transformed by time. It Will Not Be The Same, But It Might Be Beautiful illuminates that what remains—even through environmental demise—can inspire wonder, help us understand the past, and embolden resilience in the future.

I have not experienced a more important time to consider stability, vulnerability, strength, and insecurity as now. I am in the Wrangell Mountains in Alaska. Although I spend a great amount of time here, my home is on the Puebloan lands that are currently called Albuquerque. I am thankful to those who came before me on these lands, in New Mexico and Alaska, and everywhere in between.

This is a time of great insecurity and change—it brings an air of discomfort and unpredictability and vulnerability. Even so, an invitation to discuss the Anthropocene merited an easy yes from me.

Thinking about change makes people feel shaky, wobbly, and tottering. My entire art practice has been dedicated to being in change, witnessing it, and creating space to be productive within it. I understand that as part of any ecology, everything is always in a state of change.

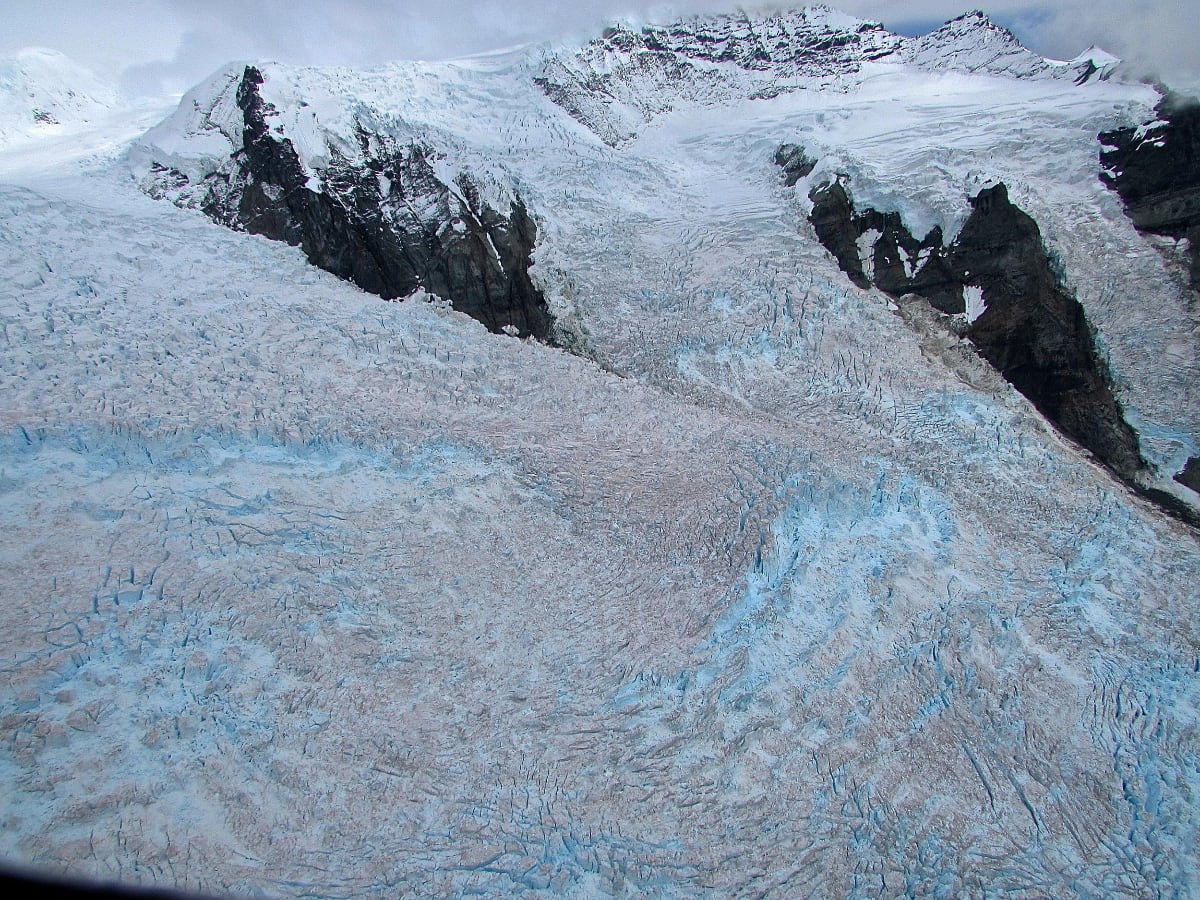

Stability and permanence are fantasies. The future is constantly slipping into the past. We are spinning and hurtling through space on a ball of stardust. Seas slosh in their tides, the moon fluctuates, water evaporates, this glacier grumbles. Evolution is happening as redwood trees in California are surrounded by flames and as polar bears lose their glacial ice.

Inside of you, whole ecosystems of bacteria and microbes are living out millions of lifetimes. The basis of life is change. I approach the Anthropocene, this time defined by change, as an opportunity, not something to fear.

I want to understand how I can relate to things even as they change. Especially because they change. I keep coming to McCarthy, Alaska because of its glaciers, to witness their changes alongside my own changes.

Glaciers are often described as fragile. They are, and they are not. Glaciers carve and shape the landscape around them. They gouge and rip and rumble like bulldozers. Glaciers are at once vulnerable and immensely strong.

I desire to not be rigid and inflexible, but to allow myself to feel vulnerable to the complexity of change. I want to be responsive to what surrounds me, even if that forces me to take on new forms.

I want to move—and be moved. The surface of a glacier is covered with cracks and ripples, stretch marks and slumps, because it has changed to fit its surroundings.

If there is any one reason why I am an artist, it is because I care deeply for this tumbling, spinning ball of stardust, and how life upon it unfolds.

I have a relationship with this glacier. I have watched it morph—and primarily shrink—over the years. As it transforms, I want to observe what that change looks like, sounds like, feels like. This glacier surprises me and sombers me and sometimes fills me with glee. This caring has allowed me to explore what it means to care for something very, very different from myself. This thing is thousands of years old and half a mile thick. It roars and burps. Parts of it are dangerous and always distant. Parts of it are familiar and fun. I feel empathy for this much-larger-than-human entity. Caring for glaciers has taught me about loving something even as it disappears. It has given me a practical understanding of deep time and distance. More than anything, this landscape offers up metaphors that I have returned to repeatedly.

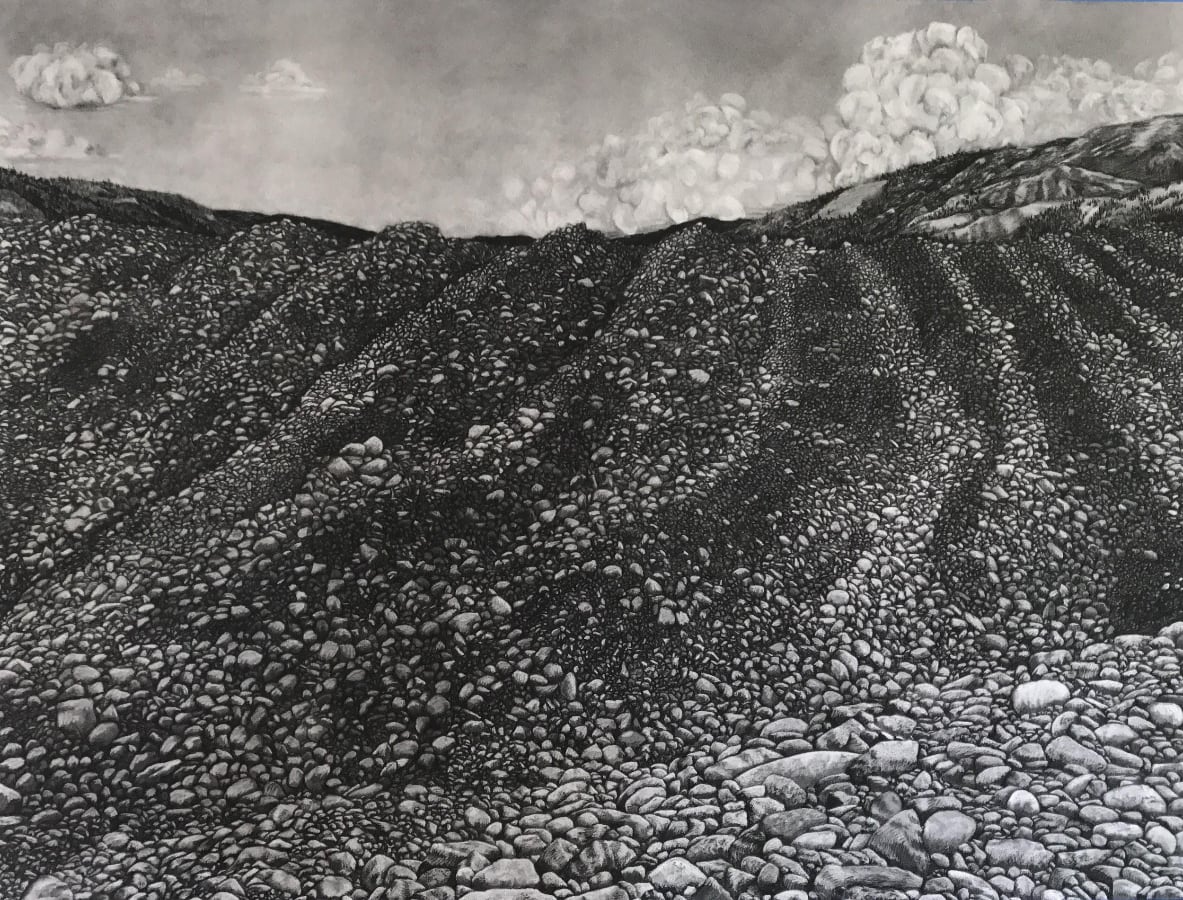

For many years, I have made work about geologic displacements. Piles of rocks.

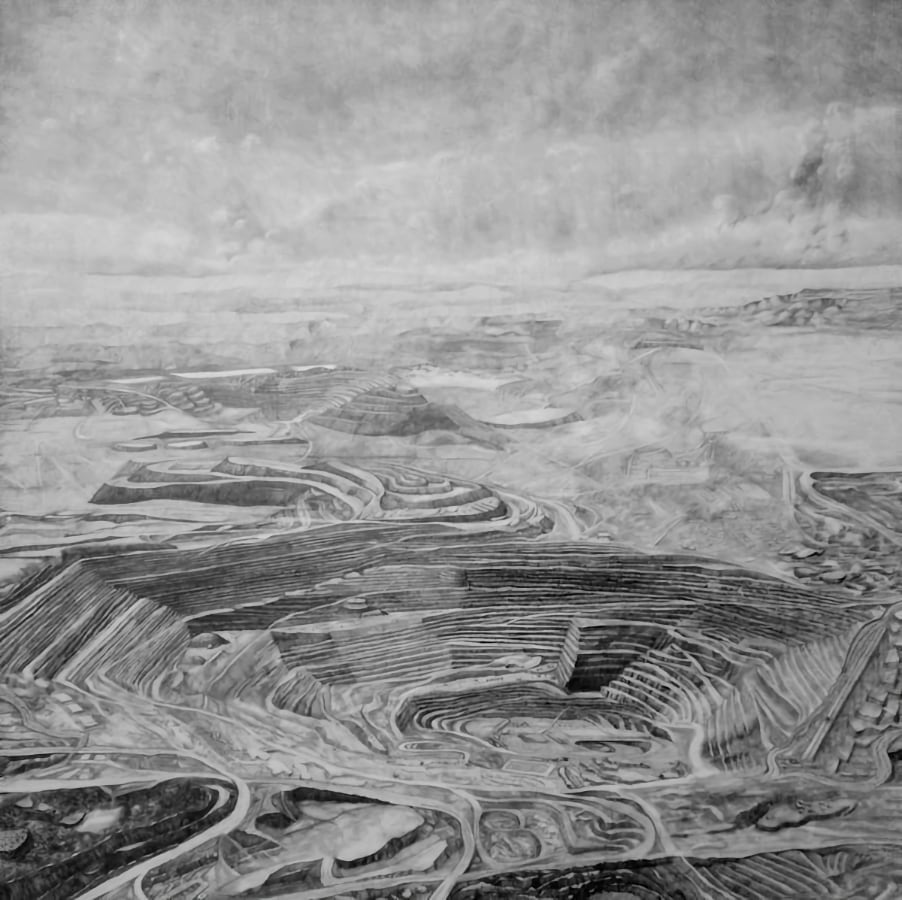

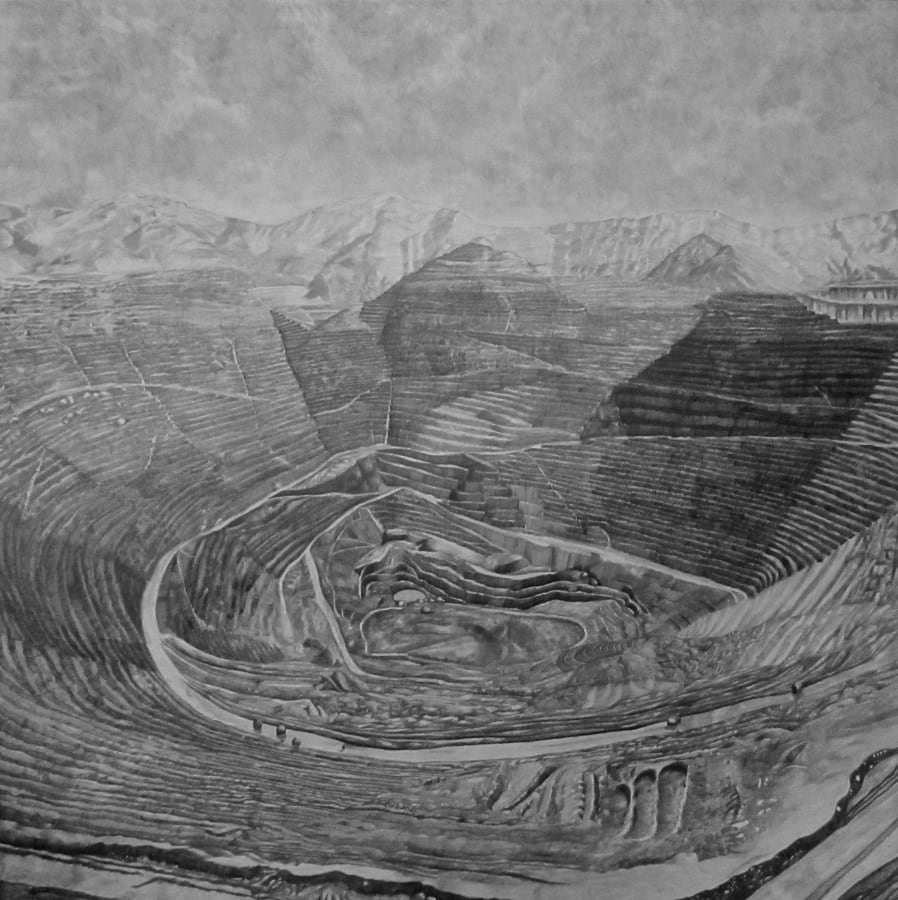

Strip mines.

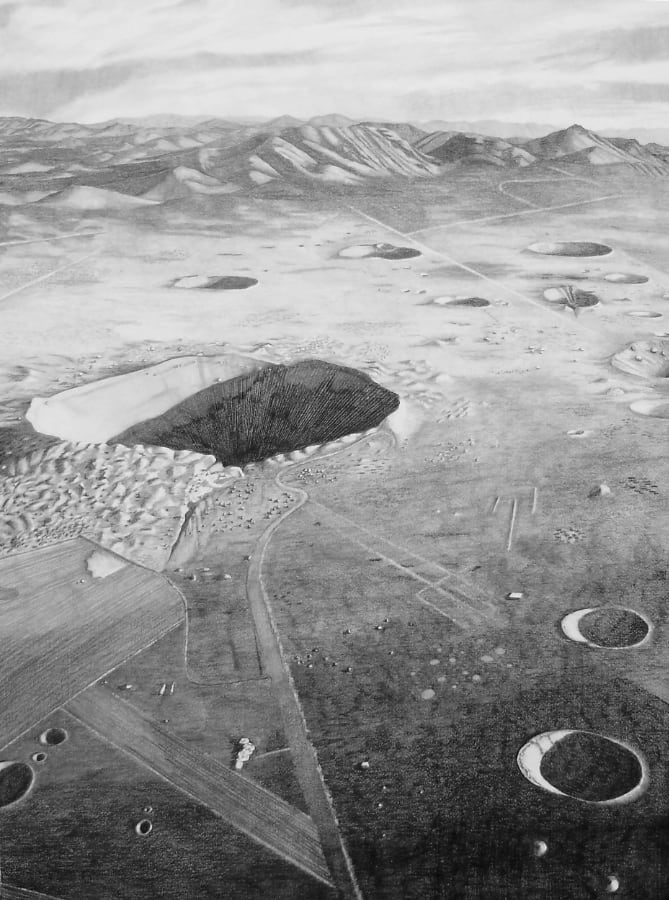

Bomb craters.

Clear cuts.

Pit mines. I want to show the impacts that consumerism has made in the landscape. I want to entice people to look at the evidence of industry that is so easy to camouflage and forget. The way that the majority of humans exist is only made possible through mines like these—massive, rumbling, highly engineered scenes of extraction. The camera that shot this image, the internet that is streaming this into your home, the device on which you view this, even the chair you are sitting on, the clothes you are wearing, the contact lenses on your eyeballs, the medicines you might have taken this morning, the mug which held your coffee—none of these would be possible without extractive industry.

We have created systems that stabilize dominant society, and in the process, have destabilized the earth. Vast portions of the planet have been sacrificed. I uphold these sites as monuments to what has been destroyed and obfuscated in that process—ecological systems, Indigenous cultures, workers’ rights, and the interconnectedness of life. These holes in the ground will not go away. But the power that created them can, and will, be challenged.

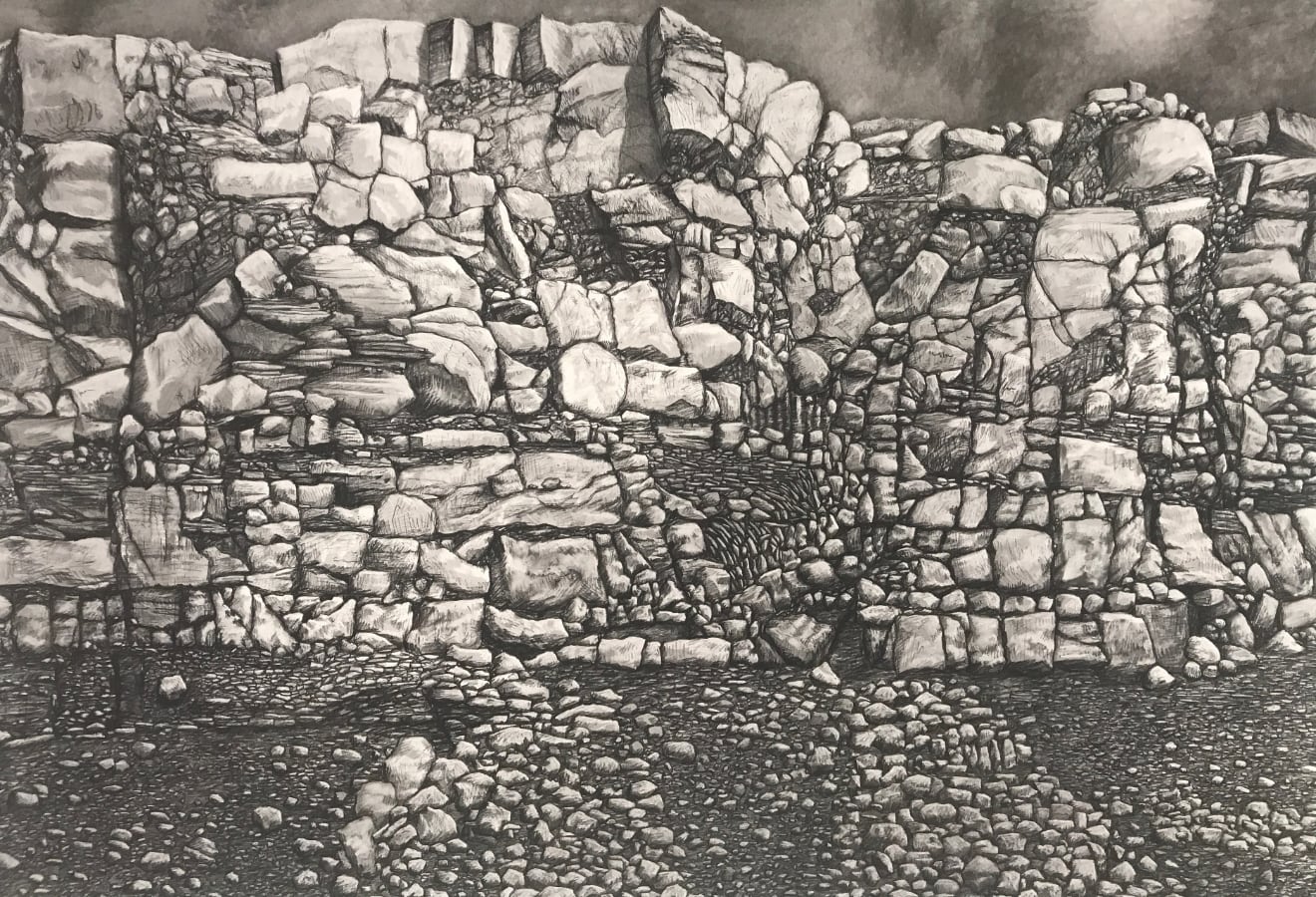

This is a drawing of a quarry in Indiana. The stone that came from this quarry became the US Pentagon. This delicate and crumbling place gives me hope when I think about the seeming dominance of the US Military. Very powerful things can erode. I have thought deeply about monuments, a subject at the center of much-needed public dialogue and action right now. I have wondered, if change is the only constant, why do we try to make something permanent by carving it in stone? Because of my relationship to geology, and to glaciers, and to mines, I see stone as something that has been formed and something that will keep transforming.

I was able to build a monument for the city of Indianapolis over the last several years. Working with the local community and engaging the geology of the area, I placed a large fractured block of limestone at the new Indianapolis Justice Center. It is a monument to the changing shape of power. It will crumble. This block will not be maintained, and it will eventually return to the soil. This block was installed early this year, before I knew that Ahmaud Arbery had been killed by white vigilantes outside of Brunswick, Georgia. Before George Floyd was killed by the Minneapolis police. Before police killed Breonna Taylor as she slept in her bed. As the force and funding of police come into public questioning, I am honored and invigorated to create something that will remind law enforcement, judges, and lawyers that power is relational, that it shifts and can always take on new forms.

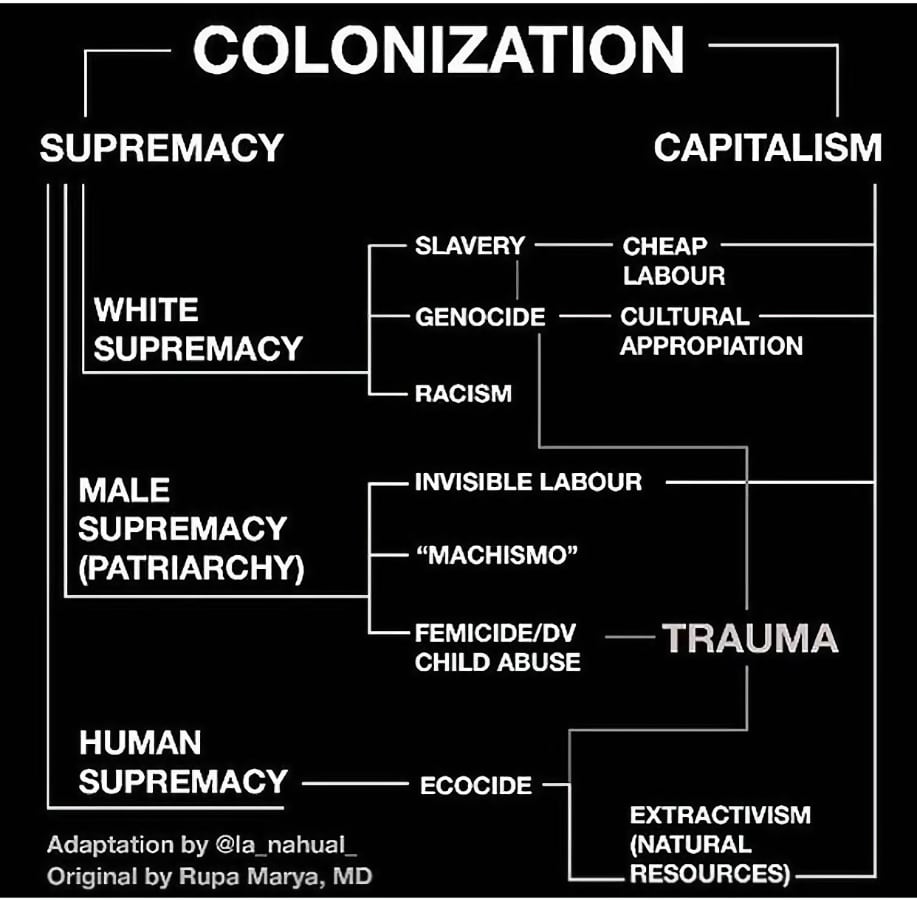

From my perspective, the Anthropocene is too often framed as a simple state of nature, a symptom of progress, a geologic era that is passively inscribed in stone. The Anthropocene is the result of the exploitation of living systems for the creation of wealth and ease. I am committed to seeing how our time is the product of white supremacy, patriarchy, capitalism, extractivism, and American exceptionalism. There is no way and no need to simplify this matter—our way of life is rooted in the oppression and erasure of people and systems that do not serve dominant, profit-oriented society.

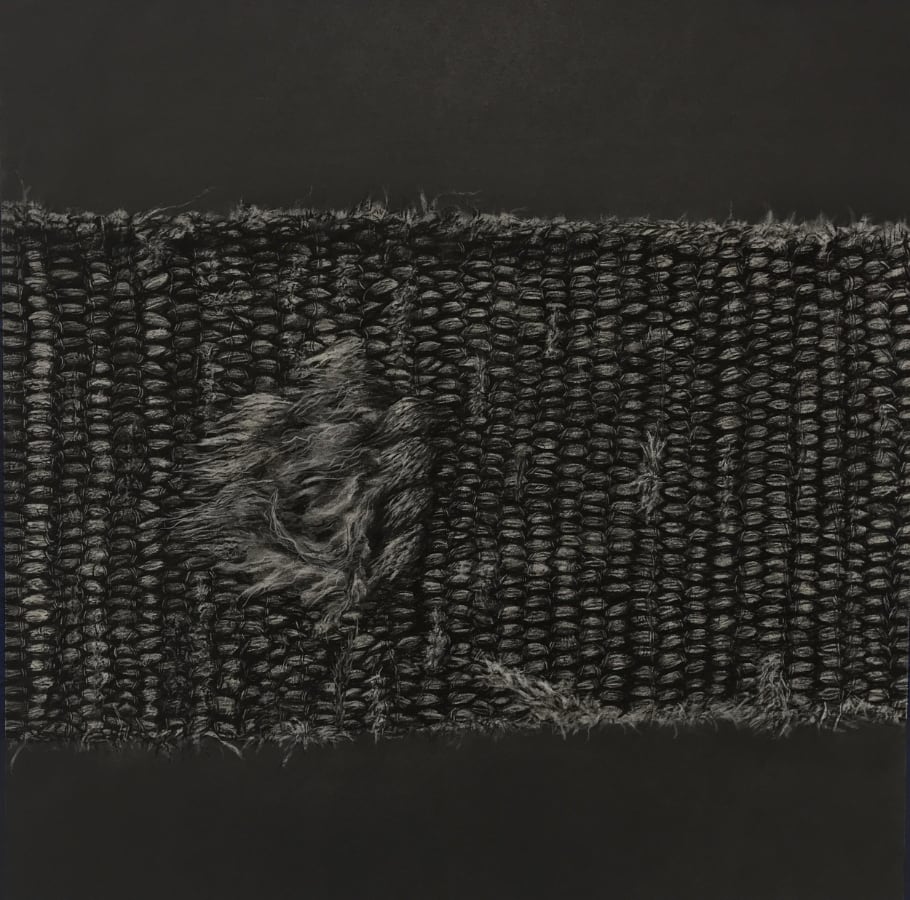

In recent months, I have become increasingly interested in the fraying of power. This moment in time, this very insecure moment, seems to be a time of fissures and ruptures and breaks. But as we are facing social, ecological, and political upheavals, I am determined to focus on what emerges.

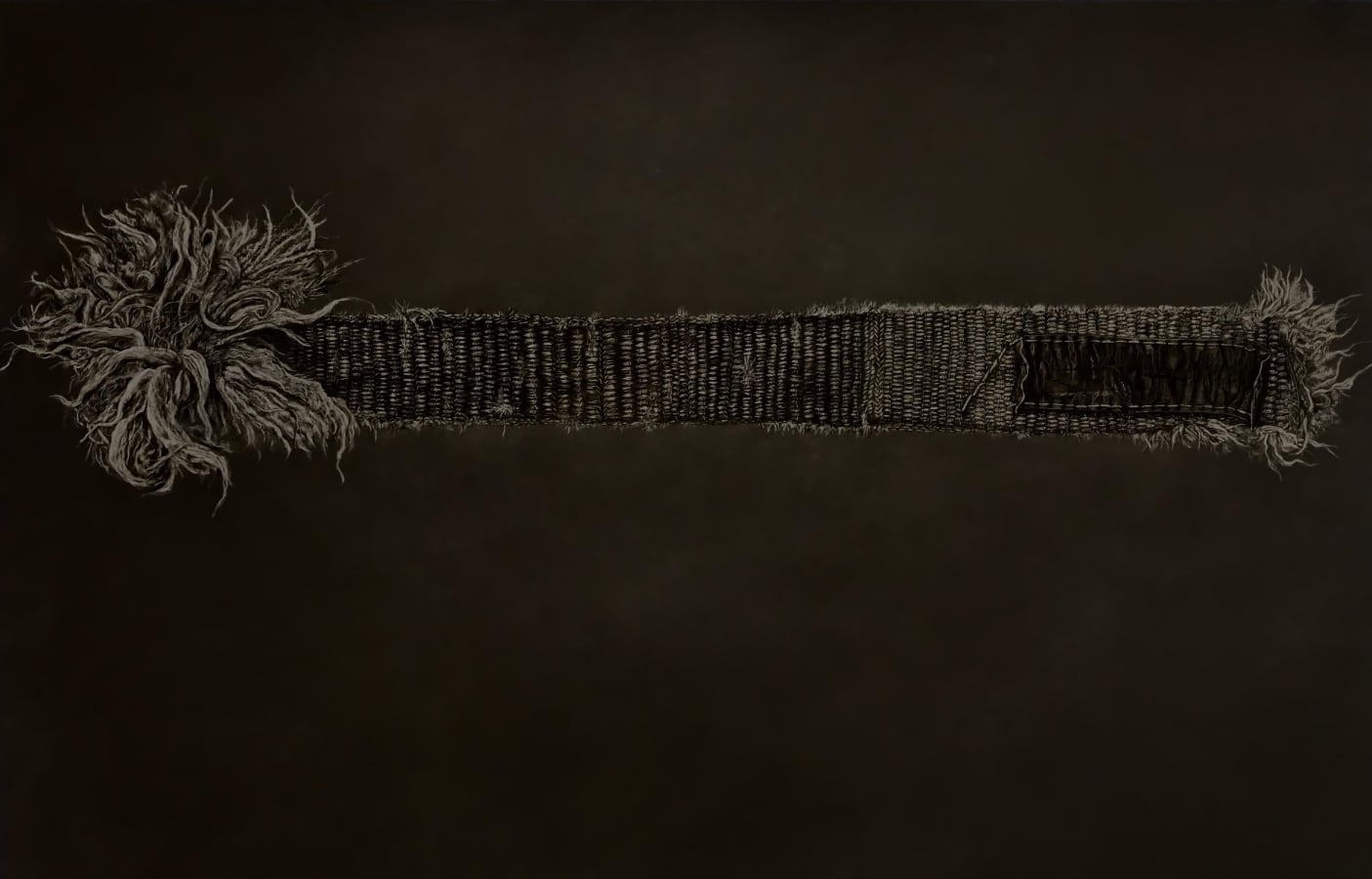

I found this strap deep in a forest. It is mysterious and intriguing. It is the most exhausted thing I have held in my hands. This strap has held great weight. It has been trusted. My meticulous drawing process allows me to seek out the faith that a person once invested in this strap.

Looking at these forms, I contemplate something that might appear obsolete, used up, of no use. Making these drawings of the strap in this frayed form allows me to understand the strength it once had.

What happens when the things we trust fail, and when the things we depend on break? They continue to hold an aura of that relationship. This strap is a document of everything it ever did.

Although the opposite of broken is whole, you cannot unbreak something. These drawings ask, what comes after the breaking point? In exploring this thing that is done doing what it was meant to do, I feel gratitude. I want to dignify what remains.

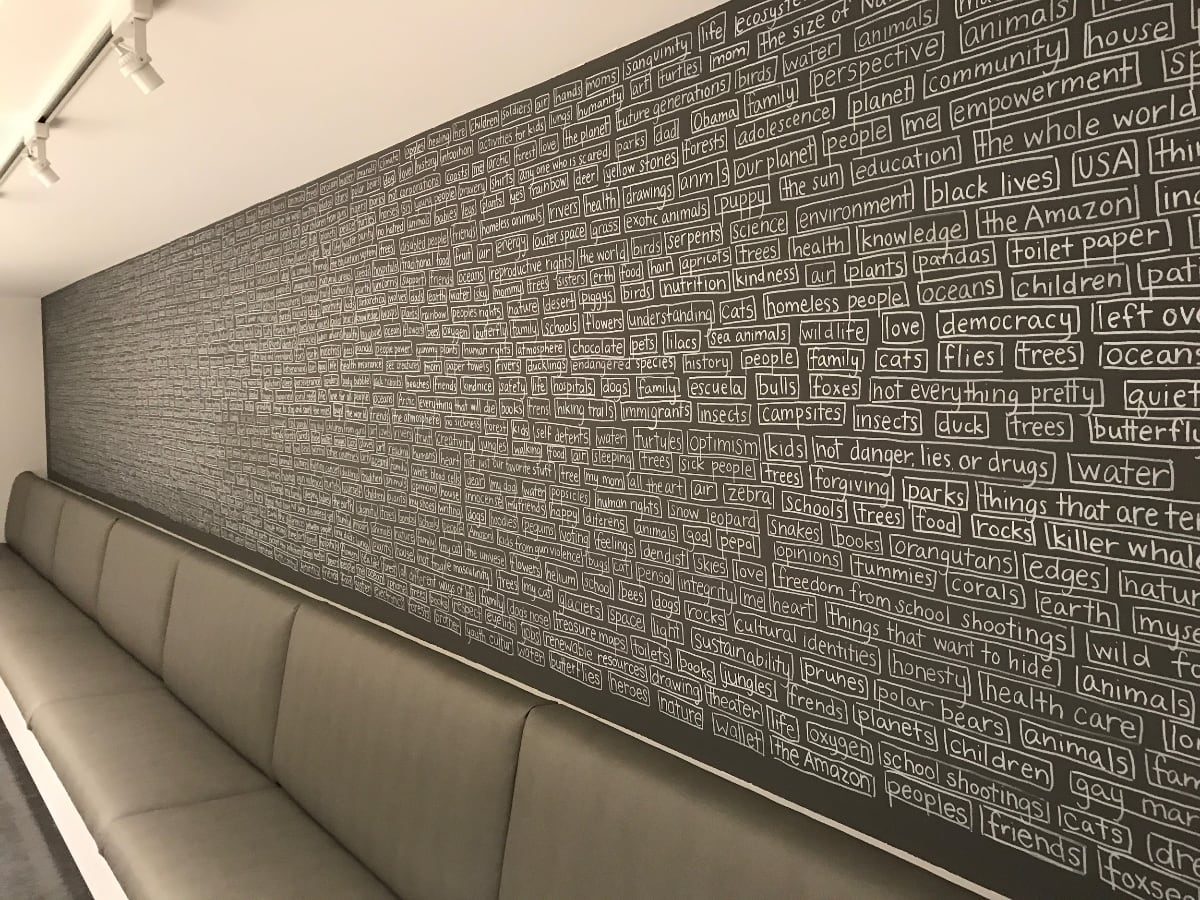

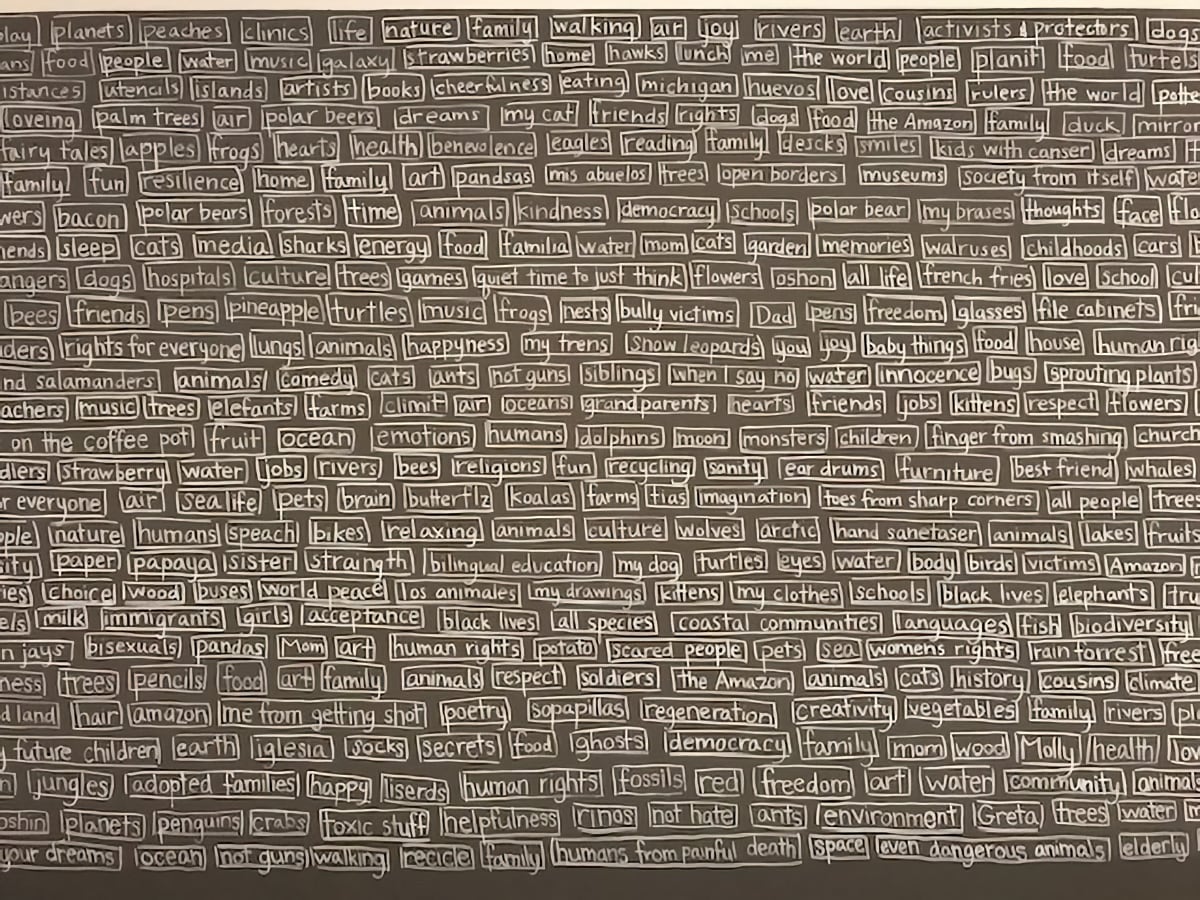

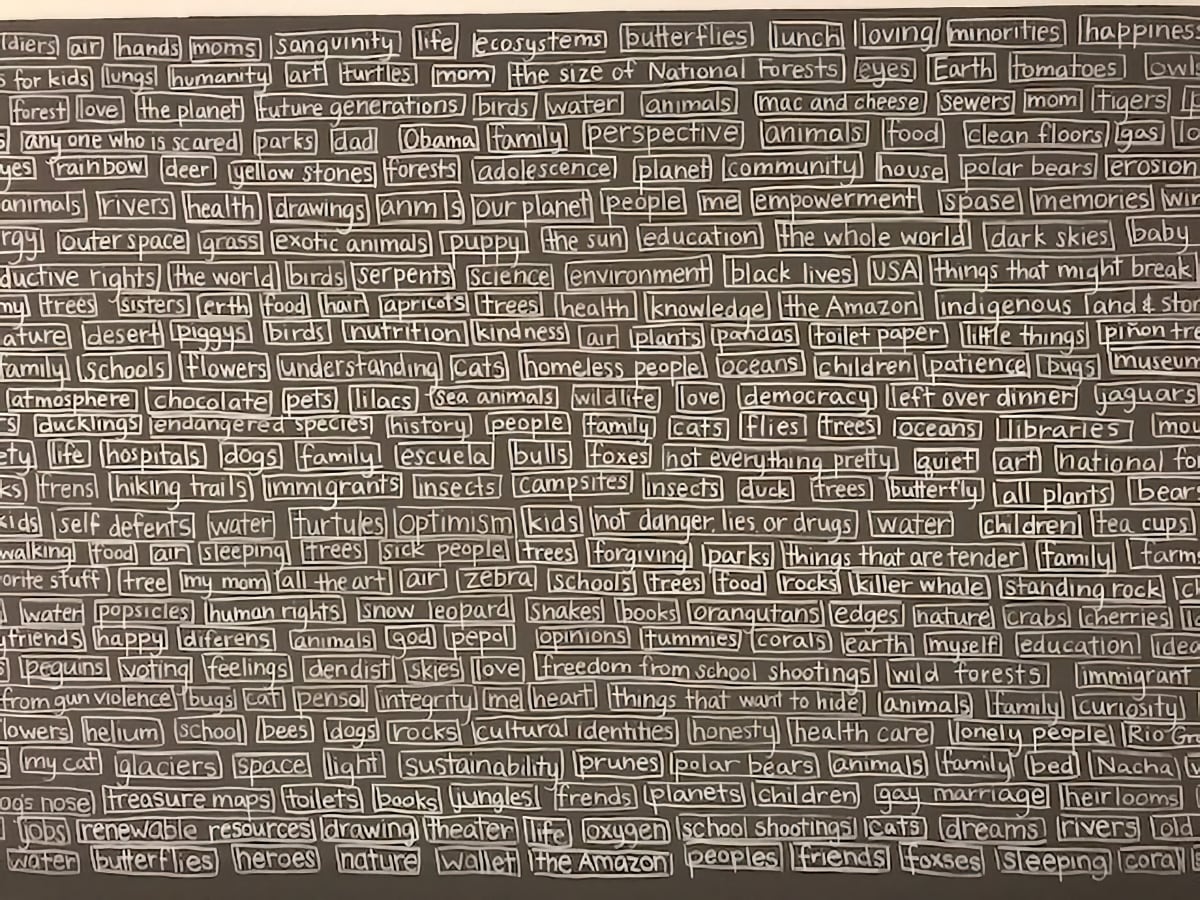

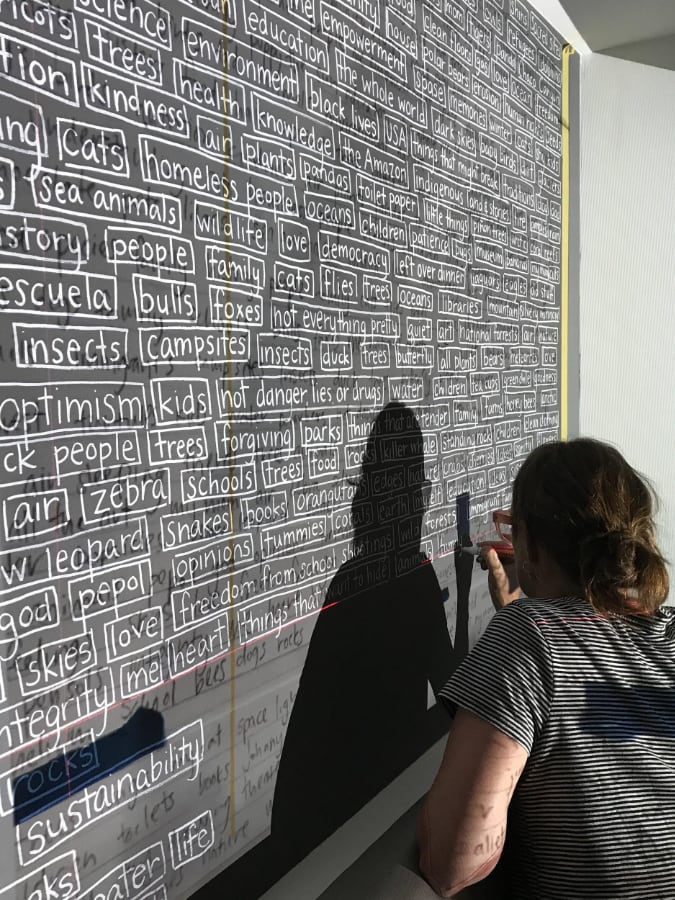

What remains? What stays intact? What needs to be preserved? These questions inspire me. Last autumn, with the education team at SITE Santa Fe, we asked nearly 500 schoolchildren what they thought needed to be protected. We compiled thousands of words, and in rewriting them, I created this mural in the education wing of the museum. The answers are poignant, funny, and profound.

The repetition of certain words showed what the kids were most deeply concerned about: Immigrant children. My Mom. Rivers. Clean air. Me from getting shot. Polar bears. Trees.

As I talked to the kids during this process, it was clear that they see their own futures as bound up with everything on this list. The instability of the environment and the social injustices of our time make them insecure and force them to be aware of a larger interconnectedness. In its density and scale, this mural also asks audiences, “What are you protecting for these kids? What do we need to do now to express our care for their future?”

I am so excited to have several opportunities to create more crowdsourced murals. In September I will think through permanence and change with two murals in Boulder, Colorado. I also will be creating murals with the Anchorage Museum next spring around questions of shelter and refuge.

Working with young people motivates me to keep finding ways to demystify and dignify change. I had terrible growing pains growing up, but now I have nothing but gratitude for my able adult legs. Climate devastation is terrifying, but it is beginning to create much-needed behavioral changes in what we consume and how we understand our impacts.

Black, Indigenous, and People of Color have been fighting racial injustice, and the whole world is starting to join in that struggle. To be in denial of change is not only unnatural, it also does not allow for a more holistic future to emerge. When we start to implicate ourselves in the change, we go through the growing pains, and then we also learn to be nimble. I have often stated that It Will Not Be The Same, But It Might Be Beautiful, which has become the title for my newest, ongoing work.

This summer, with the support of the National Performance Network and the Speranza Foundation, I am creating a multimedia project that will address change and impermanence, looking at breakage and emergence, human legacies, and geologic time. I have been working with Mike Conti, an amazing Alaskan cinematographer and co-conspirator.

These are puzzle stones, rocks that have been shattered by extreme temperature shifts. Here in McCarthy, they have recently been ejected by a glacier. They are enigmatic and alluring, fragile and strong.

I am inspired to make this work because we can witness these rocks in the midst of a transformation. This time of rapid change asks us to be involved and responsive as it happens. We cannot wait to see how the world remakes itself. I am finding it increasingly important to explore how we care for something even as it crumbles. I started this work because I often feel that the world is in pieces and I have no sure way to reassemble it.

But this state of insecurity and crumbling does not make me stop seeking what might come next. The fact that I know this planet is forever impacted by my actions does not mean I will abandon those actions. To acknowledge our roles in systemic oppression and injustice does not mean we have fixed the problem.

I wanted to see what would happen if I asked people to carefully and self-consciously pick up these rocks that are very unstable.

How do we engage with change, and take an active role in change, even if that is very uncomfortable and causes moments of instability?

How do we act in a way that asserts that even though the future will not be the same, it might be beautiful?

The artist thanks the Anchorage Museum, the Wrangell Mountains Center, NPN, and the Speranza Foundation. This work would not be happening without their support.

All photos: Nina Elder and Mike Conti. All materials property of Nina Elder. Any entity must seek permission to reproduce or represent content for any purpose. Requests to reuse materials can be directed here.

This photo essay was published on September 30, 2020.

About the Artist

Artist and researcher Nina Elder creates projects that reveal humanity’s dependence on, and interruption of, the natural world. With a focus on changing cultures and ecologies, Nina advocates for collaboration, fostering relationships between institutions, artists, scientists and diverse communities. She is the co-founder of the Wheelhouse Institute, a women’s climate leadership initiative.