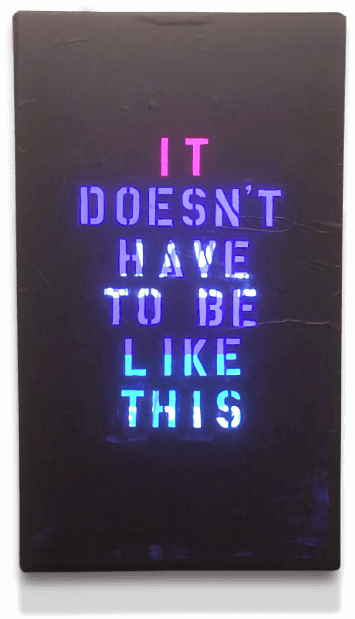

Jonathan Allen, Interruption 203, Borough Hall subway station, April 17, 2020.

Paint and plastic on video screen, 58 × 34 in. www.jonathanallen.org.

Focus Group

Artists

Focus Group

Technicians & Designers

Focus Group

Presenters

Focus Group

Agents, Managers & Producers

Other ways to read this report

Contracts are moral documents. They are also enforcement tools. Drafting an equity-driven contract raises tensions: tensions between new and old models of relationship, between a vision rooted in relationship and the pressures of capitalism, and between the desire for collaboration in the field and the reality that adversarial situations happen.

In an effort to wrestle with these tensions—and in response to Phase 1 of Creating New Futures (CNF)—a Contracts Working Group was formed as part of CNF Phase 2. The group, whose core laborers include Sandy Garcia, Ben Levine, Sarah Lewitus, and Hope Mohr, have spent over a year working with other arts workers engaged in CNF to create contractual documents built from a place of justice and transparency, clarifying the terms of the engagement for both parties to the contract (the Artist/Company and the Presenter) not only legally, but in terms of relationship and community. Katie Gorum was also an early member of the Contracts Working Group, whose work as a technical director was instrumental in including technician/designers, who may review technical riders but are normally not part of the engagement contract negotiation.

The Contracts Working Group (Hope, Ben, Sarah and Sandy) represent a range of geographic, professional, disability status, racial, gender and sexual identities. We are a majority-white, majority non-disabled group and acknowledge the influence that identity brings to this process. We share for the sake of transparency that within CNF our work has been supported through a mix of pro-bono time contributions and through honoraria from CNF’s funds. Each of us were compensated $250 from NPN for the production of this blog post.

The resulting documents produced by the Contracts Working Group include an Engagement Contract, a Presentation Participant Agreement, a Presentation Information Form, and a Production Agreement. The Contracts Working Group developed this suite of documents from an existing contract used by Dance Place, a NPN partner and 41-year-old dance presenter based in Washington, DC.

The documents are not templates, but rather are meant to serve as examples of equitable practices and as a resource for other presenters, artists, and arts professionals working with engagement contracts. The documents are by no means “done.” The work of equitable contracting is a constantly evolving process, which includes sharing our work through this blog post. Throughout the process of developing this suite of documents, the Contracts Working Group has felt, acutely, the tensions described at the top of this post. On the one hand, we want to craft a visionary document, and on the other hand, we want to offer the field a practical document that will hold up in court as a meantime strategy, while we as arts workers participate in the struggle abolition of current harmful systems “justice” in favor of decolonization and true restorative justice.

The Contracts Working Group’s top-level takeaways for equitable contracting thus far include:

- Reframe the presenter-artist/company relationship from a transactional contract model to a relationship-based agreement

- Share risk, acknowledgement of labor, and compensation for work completed

- Decentralizing the performance product so that decision-making and power are shared

Overall, these takeaways all address a shift to acknowledge labor and effort rather than product, guaranteeing that all parties are paid for their work, regardless of the final performance. They aim to foster community-building, trust, and long-term equitable working relationships.

Recently, the Contracts Working Group engaged focus groups to receive feedback on the suite of documents directly from arts workers, bringing them in to navigate this tension with us. Focus groups included:

- Artists (facilitated by Hope Mohr)

- Technicians & Designers (facilitated by Ben Levine)

- Presenters (facilitated by Sarah Lewitus)

- Agents, Managers & Producers (facilitated by Sandy Garcia)

Here, each facilitator will share their top takeaways from their respective focus group.

Focus Group

Artists

Focus Group

Technicians & Designers

Focus Group

Presenters

Focus Group

Agents, Managers & Producers

Artist Focus Group

By facilitator Hope Mohr

For a variety of reasons, many artists don’t read contracts. Contracts are intimidating. Reading one is burdensome. Artists may come to a contract with a sense of futility: the presenter holds all the negotiating power anyway, so why bother? Or a sense of stoicism: I need the job, so whatever the contract says, I’m committed. Or class privilege: whatever the terms of the contract, I’ll be financially fine.

As a field, how can we change these assumptions? Live art rests on the bodies of the artists onstage. How can we create the conditions for artists to define the terms of their engagement?

The Artist Focus Group took place on July 19, 2021. Participants included independent choreographers, freelance dancers, and an executive director of an established dance company.

A major point of discussion was the need to represent dancer interests in the context of negotiations between a presenter and a choreographer or dance company. Do credit and royalty rights extend to dancers and collaborators? Are other dancers’ interests adequately represented in presenter negotiations with choreographers and their representatives? How can presenters and choreographers bring dancers into the conversation?

One proposal was to require the signature of a dancer representative on the contract to indicate that the dancers involved in the engagement have reviewed and approved the terms. Dance Artists’ National Collective (DANC) has been leading efforts to develop a freelance dancer contract template; it’s crucial that this work be brought into conversation with efforts to develop more equitable presenter contracts. We need to coordinate and align freelance dancer advocacy with advocacy on behalf of organizations.

Live art rests on the bodies of the artists onstage. How can we create the conditions for artists to define the terms of their engagement?

The artists advocated for a contract that incorporated artist compensation for administrative and overhead costs. For example, reading and discussing contracts takes time. Venue staff are often salaried and paid to do this work, but dancers and artists are not. The artists were enthusiastic in support of a contract that placed a value on pre-engagement labor, which can include rehearsal, planning, and contract negotiation.

Artists expressed concerns that the proposed engagement contract was too long and thus burdensome to read, which raised the question of how to make the document both comprehensive and accessible. One solution would be to have a contract walk-through/talk-through session and to pay the artist for their engagement and time for this phase of the negotiation.

Timing, the artists noted, is important. One artist shared their experience of not receiving a contract until they walked into the theater for tech rehearsal. Artists talked about the need for a preliminary agreement guaranteeing that there would in fact be a contract and setting forth the timeline for the negotiation and its basic terms.

One artist said that any artistic content, such as the program note, should be the exclusive domain of the artist and not up for negotiation. The artists also voiced concerns over media and licensing rights, saying that the contract gave too much power to the presenter regarding third-party licensing and that it should provide more information regarding rights to digital content and the number of years that rights to media content will exist.

Artists also expressed concern that a contract template would reify waning models of production, i.e., the touring company. Few artists tour these days. How can a contract be scalable and customizable for different contexts: nonproscenium, museums, durational residencies, projects involving community members, and social practice projects?

Equitable contracting won’t change underlying economic realities—some artists have more bargaining power than others. Depending on resources, artists have different levels of capacity to refuse the terms of a contract. Universal Basic Income is a better solution to pervasive economic inequity than any letter of agreement. Only by providing artists with basic economic security will we create a world where, in the words of focus group participant Lionel Popkin, performance opportunities are “choices of interaction, not fiscal necessity.”

Focus Group

Artists

Focus Group

Technicians & Designers

Focus Group

Presenters

Focus Group

Agents, Managers & Producers

Technicians & Designers Focus Group

By facilitator Ben Levine

Technicians and designers rarely see the engagement contract between an artist/company and a presenter. Despite this, having a successful working relationship between the presenter and/or venue production personnel and the artist/company production team is paramount to the success of the engagement. In the Technicians and Designers Focus Group we discussed the power play and often adversarial relationships felt between presenters/venues and artists/companies and grappled with how this suite of contract documents can begin to shift the culture of the field of technical theater.

How do we shift away from the grumpy technician archetype? How does venue staff shift away from a culture of “no” and find their “sacred yes”?

The conversation feels impossibly layered. Presenters and venues have different capacities (financial, architectural, staffing, equipment/inventory-wise). Some presenters have their own venues while others don’t. Some venues work with union crews. Some artists/companies work with union designers. Artists have widely differing expectations of presenters, particularly across dance genres and points in the career spectrum.

And there are layers of privilege—of race, gender, sexuality, and ability. The field of technical theater is dominated by white men. When designers of color enter a venue run predominantly or entirely by white folks, how can they advocate for themselves and their work while navigating layers of privilege on top of the presenter/artist power dynamics? The contract must support these designers rather than reinforce the need for artist/company production staff to prove their ability, knowledge, skill, and artistry to presenter/venue staff.

How do we shift away from the grumpy technician archetype? How does venue staff shift away from a culture of “no” and find their “sacred yes”?

Unlike in the theater world where production teams nearly always include a stage manager, lighting designer, sound designer, scenic designer, costume designer, etc., the underfunded dance world often requires production staff to wear multiple hats. The role of the stage manager, in particular, is misunderstood and undervalued. Examining the Presentation Information Form, which aims to outline what technical/design staff the artist/company will provide, we consider what are reasonable expectations of designers versus presenter staff. When is it appropriate to ask a venue technician to make an artistic decision or voice an artistic opinion? How do we define “artistic decision”?

Despite the density and thoroughness of the CNF contract documents, this is only half the picture. The CNF documents protect dance companies and dance presenters, but don’t directly protect individuals. Additional contracts between dance companies and designers, for example, must also uphold values of equity and justice. While Dance Artists’ National Collective (DANC) is working on creating a dancer contract template, to our knowledge there are currently no parallel efforts to create a designer contract template beyond the context of unions. It feels that there is much work still to be done!

Focus Group

Artists

Focus Group

Technicians & Designers

Focus Group

Presenters

Focus Group

Agents, Managers & Producers

Presenters Focus Group

By facilitator Sarah Lewitus

Mutuality stood out as an important focus of equitable contracting for the Presenters Focus Group. Presenters appreciated the approach of the artist and presenter working together to assemble the “puzzle” of the engagement through the contracting process. The clarity that, for each section of the contract, “The Artist/Company will provide X; The Presenter will provide X; The Parties to the Contract will provide X” illustrates that both parties are showing up with things to give and both parties have things to take.

Contractual wording that is intentionally open, readable, and digestible (rather than “legalese”) felt like a benefit for both parties in support of the mutuality being built throughout the document. But there can be a downside to openness: a decrease in precision of language can leave contractual points up for interpretation, and generally, the party with more power gets to determine that interpretation. As presenters inside of institutions, the resources we wield often tip the balance of power in our favor, disrupting the mutuality of our agreement. Within the documents, presenters noted the struggle to balance accessible language with precise language, a balance necessary to protect both artists and presenters when it comes to working with a lens of mutuality.

Zooming out, we asked: “What is the purpose of this document? Is it an ethical, aspirational document, or a document meant to protect each party, and therefore necessarily adversarial?” The answer we, as a focus group, not-so-comfortably landed on was that perhaps it needs to be both at once. This duality creates tension in more than just the tone of language, it also impacts the way that we, as presenters, manage the process of contracting from start to finish.

First, we need to know what we mean by the “start” of an engagement. Does equitable contracting require a pre-contract step, where artists who have had multiple, meaningful conversations with presenters are paid for their time if those conversations do not move to contract? Is there an offer letter or short letter of agreement when an engagement does move forward, prior to the full contract? The current suite of contractual documents developed by the CNF Contracts Working Group does not address either of these circumstances. We contemplated: Is it better for us, as presenters, to get the contract out earlier, knowing less about the engagement and leaving a number of “unknowns” in the document, or to wait until much closer to the engagement, meaning that we will know the scope of the project upon contracting, but that both parties will have to wait longer to have the countersigned document in hand? These questions of contractual timing must be carefully considered by presenters engaging in equitable contracting.

We asked, "Is this an ethical, aspirational document, or a document meant to protect each party, and therefore necessarily adversarial?" We not-so-comfortably landed on the answer that perhaps it needs to be both at once.

Next, we need to consider what it is we are contracting for. Are we commissioning, supporting a development process, presenting, producing, or some combination of these? And how do our contract documents look different in each of these cases to create clarity between artist and presenter? How personalized can—or should—a contract be for each engagement?

We also contemplated how the documents are shared between presenter and artist/company. In a contracting process between a presenter and an artist/company, it is rare that the entire artistic team reads a contract; it may be that only the “lead” artist reads and executes. If the artist has a manager/agent, it may be that none of the artists participating in a project have read or signed an individual presenter’s contract ahead of an engagement. As presenters, we know that this can cause problems. Maybe an artist/company’s designer never connected with the presenter’s technical director, and two weeks before the presentation we realize that an expensive rental is needed, creating a messy negotiation. In our focus group, the presenters contemplated how we might organize the contractual process into manageable bites that align with the artistic journey and bring all stakeholders within an engagement into the process. To do that, perhaps we must move further away from a template model (because although the suite of documents are not intended as templates, they can easily be mistaken as templates due to their formatting) and instead create a series of equitable framing questions for presenters to consider prior to developing any contractual document.

The CNF Contracts Working Group suggests that presenters host a contract walk-through with artists/companies upon issuing the contract, prior to signing. The Presenters Focus Group agreed that this could be beneficial to catch any “red flags” in the engagement prior to signing, to make sure that artists are aware of presenters’ idiosyncrasies prior to committing to engage, and to create space for artists to add contractual points of their own. However, the idea of a walk-through brought up another important topic: capacity and labor. For both presenters and artists, the equitable contracting process can create extra steps that may not be feasible for either party to adopt quickly, or at all, without additional financial and personnel resources.

One example of additional labor on the presenters’ end is the equitable payment model. An essential component of the equitable contracting conversation is the shift from holding artist compensation until the completion of an engagement to, instead, scheduling multiple payments throughout the engagement. This change in payment model acknowledges the continuous labor done by the artists in any engagement with a presenter. While the Presenters Focus Group agreed that this multiple-payment structure must be maintained, it’s worth noting that adding multiple payments throughout the course of an engagement creates additional administrative labor for the presenter, as they must track and process payment timelines, often concurrently across multiple engagements with a possibility of different “benchmarks” to be completed prior to each payment for every engagement. This can be especially tricky if the presenter works under a larger institution like a university, as the university may not make it simple for a presenter to pay artists prior to a performance/presentation. No matter the hurdles, it is clear that the shift to multiple payments must be part of our work as presenters going forward—we must build new systems to accommodate the realities of the artist’s labor.

As presenters, we hope that the relationship we are building with artists we are contracting is a permanent one, therefore a few weeks of additional negotiating and logistics around equitable contracting should feel like a blip.

The Presenters Focus Group acknowledged that, in the short term, the changes in practice suggested by equitable contracting may create additional labor for the artists we work with. We discussed that, as presenters, we hope that the relationship we are building with artists we are contracting is a permanent one, therefore a few weeks of additional negotiating and logistics around equitable contracting should feel like a blip. That being said, the extra time to hold a contract walk-through and generally to be in detailed dialogue about the mechanics of the contract itself creates labor that many artists do not currently take on when contracted. Several of the presenters in the focus group noted that artists have said to them outright, “I’m not going to read every line of this; I just want to trust that you have my best interests at heart.” This can be particularly true in the case of artists for whom English is not their first language. To mitigate this, we as presenters must account for this administrative time in our artist fees.

One presenter in the focus group noted that, “This document is like a Google Map of the road trip: it outlines where we think we’re going, the presenter and the artist/company together. As we as presenters make the first draft of that map, we must figure out how to insert as much care as possible into the journey.”

To close, it is worth noting that presenters who took part in this focus group are all doing their best to move to a place of equitable contracting. We certainly all have work to do. But still, notably missing from these conversations are presenters who are not making an effort to move towards equity in their contracting work at all. This challenge was also noted in the Phase 1 Creating New Futures “Presenter Perspectives” section. Going forward in our equitable contracting advocacy, we must figure out how to bring those folks to the table as well.

Focus Group

Artists

Focus Group

Technicians & Designers

Focus Group

Presenters

Focus Group

Agents, Managers & Producers

Agents, Managers, and Producers Focus Group

By facilitator Sandy Garcia

Digging into the contract and suite of documents, the Agents, Managers, and Producers Focus Group had specific comments on select clauses as well as on the overall structure and length of the contract and supplementary documents. They found it important not to view these as templates, but rather as documents that help prompt conversations amongst those in our field who are interested in reimagining best practices that focus on the relationship between artists and their representatives (agents, managers, producers) and presenters as opposed to the “product,” aka the performance.

Early on in our conversation, we questioned whether our discussion should focus solely on the mechanics of the contract language or if it should include the negotiation of fair and equitable compensation. Because contracting at its core relates to describing and approaching the relationship, we started by focusing on specific clauses. However, it became clear during our discussion that within the topic of contract mechanics, fair and equitable compensation was unavoidable and not mutually exclusive. The reason for our efforts to redefine relationships through contract language is to support fair and equitable practices, which include fair compensation.

RELATIONSHIP VS. PRODUCT

It was evident to our group that Dance Place was making a concerted effort to center their contracts around relationship, rather than product, and that language that upheld and advocated for open lines of communication, acknowledgment of labor, process, and transparency was built into their contract and addenda. That being said, having so many documents could seem unwieldy and redundant. We felt that further streamlining the content of the documents would be helpful in making this process less cumbersome for all.

The contract describes “completed work” as: “’completed’ to be defined by the Artist/Company; i.e. not a work in process” (page 4, item C.1.). This brought to the forefront the question, how can we align expectations for the performance experience? As mentioned above in the artist section, the touring company is a “waning model of production” and fewer artists are touring these days. Covid has also resulted in projects being presented in different stages of completion. While the group was uncertain if the definition of “completed work” was clear enough, they appreciated its inclusion as a way to prompt the presenter, artist, and their representative to discuss expectations ahead of time and ensure that all were on the same page in terms of what stage the work would be in when presented, as well as establishing proper titling, especially if the company was there as part of a developmental or technical residency. They emphasized that defining the work needs to be artist driven—transparency, communication, and setting expectations are all a must for a positive outcome for all and preserving the relationship. They also felt that it would be helpful for Dance Place to provide definitions for different stages of work to be presented to ensure that parties are on the same page when entering into conversations about performance expectations.

defining the work needs to be artist driven—transparency, communication, and setting expectations are all a must for a positive outcome for all and preserving the relationship.

BENCHMARKS & COMPENSATION

Benchmarks

The group appreciated the document’s clarity pertaining to Benchmarks (aka, services rendered or deliverables) to ensure that all parties are on similar pages throughout the engagement process and that artists are being compensated for their labor as they meet the benchmarks necessary to complete the terms of the agreement. In some instances, the agent, manager, or producer mentioned that they might add to the list of benchmarks depending on the presentation.

One participant observed that the benchmarks did not specify services or payment for services provided by artist representatives such as agents, managers, and producers for the artist’s engagement. This could be a challenge to address consistently, as many representatives work differently with their artists and have their own internal agreements. Additionally presenters may be working with artists who do not have representation or with artists who are working with representation without knowing that arrangement. We questioned how or if that could be reflected/amended in the presenters contract, but did not arrive at a clear solution.

Oftentimes if an artist is working with an agent, manager, or producer, they will have conversations with the presenter on behalf of the artist. The contract review timelines built into the Dance Place contract are a great way to ensure communication and group reviews between all parties, but they also make the contracting process much more labor intensive—which may be untenable for all parties involved. We discussed how perhaps, as we enter into this new reimagining of contracts and relationships, this sort of labor-intensive review practice is necessary as we build new practices for our field.

Compensation

One of the participants said, “You can’t negotiate a contract without having a clear conversation about artist compensation.” Artists, their representatives and presenters may have different assumptions about what will be provided by a presenter or an artist, and the mechanics of the contract must work to prevent these. Including a payment schedule that is tied to benchmarks is a step in the right direction toward clarity and acknowledging labor that is being provided throughout the engagement process.

"You can’t negotiate a contract without having a clear conversation about artist compensation."

For many agents, managers, and producers, when we negotiate a total artist fee with a presenter, that amount includes the artist compensation as well as ours. Travel, accommodation, freight, and per diems may either be budgeted into the negotiated fee amount or structured as additional responsibilities of the presenter on top of the monetary compensation. If an engagement contract is being issued by an agent/manager/producer and those responsibilities are being provided by the presenter, the artist representative will list those items as part of the artist compensation in the contract.

In the interest of transparency and shared risk, the group appreciated the presenter including the value of their hotel costs in the contract, showing how much the presenter is investing in housing for the artist. This is useful for both grant reporting and in making the artist aware of the financial impact on the presenter should the artist request a number of rooms but not use them all or not give proper notification to cancel—accountability goes both ways.

CANCELLATION

The use of force majeure—a clause that terminates the contract and frees parties from obligations to each other due to unforeseeable circumstances—was one of the main catalysts for Creating New Futures Phase 1. A contributor noted that she appreciated that there was no stand-alone force majeure clause that called for immediate termination of the contract. Instead there was a cancellation clause that included contingency plans if a portion of the engagement couldn’t proceed as scheduled due to force majeure.

The group appreciated Dance Place’s effort in trying to work with the artist to continue the engagement and relationship rather than immediately moving toward “termination and walking away from the terms of the contract.” They also appreciated the presenter offering compensation based on an hourly rate for unexecuted activities if a cancellation was necessary. Participants wondered whether the rate was per activity or per participant for each activity, but overall appreciated Dance Place addressing and compensating activities that in many cases are considered all-inclusive.

ACCOUNTABILITY

Bullying, Sexual Harassment

Creating a safe and mutually respectful working environment is important, and the group appreciated the language centering safety in the Presentation Participant Agreement and the Youth Presentation Participant Agreement. They emphasized the importance of consistency in both these documents, as any participant may be subject to bullying or sexual harassment. The group suggested adding instructions on how to report issues as an accountability provision.

Accessibility

The group appreciated that Dance Place noted accessibility in the contract (section F), although they felt the language was too vague and subjective. The group is interested in seeing more work from CNF on creating an accessibility rider for the field.

CHANGES TO THE TOURING LANDSCAPE

Our group also commented on how the contract addresses changes we are seeing to the touring landscape, as well as where more work can be done.

Virtual

Because virtual engagements have risen in popularity, it is important to ensure that contracts include clauses specific to streaming, recording, rights, ownership of recorded content, etc., when these activities will take place. The dance field as a whole has been loose about contracting around virtual engagements, and the present contract likewise does not address them.

Recording and Photography

The group felt the clauses on recording and use of artist imagery for archival, marketing, fundraising purposes gave the presenter too much freedom to use the artist’s imagery and content without adequate permission. Additionally, companies may have agreements with their own performers or participants that restrict future use of photographs or video content if they are no longer with the company—which could be in conflict with a presenter’s clause. Therefore, our focus group found it especially important post-Covid that artists retain control over their content regardless of whether it was created by the artist or presenter during a residency at the venue. Overall the group was surprised by the language in the participant agreements that allowed the presenter to use content at their discretion and would strike the language if they received it for review.

Exclusivity

Given the challenges of touring for artists, the group appreciated Dance Place’s willingness to offer an artist-friendly exclusivity clause of 35 miles and 90 days.

A self-education rider states that the presenter acknowledges that the artist’s work is queer-centered, POC-centered, or within a lineage of Indigenous artists, and that the presenter will self-educate before artist’s arrival.

ADDITIONAL RIDERS

Intersectionality Rider

During our conversation a producer shared how in touring predominantly QTPOC artists, she includes a self-education rider in her contracts. The rider states that the presenter acknowledges that the artist’s work is queer-centered, POC-centered, or within a lineage of Indigenous artists, and that the presenter will self-educate before artist’s arrival. The addendum includes a list of resources and asks the presenter to provide an introduction of staff and company members that includes but is not limited to pronoun usage and name tags if requested at the beginning of load-in. A manager in the peer group expressed that this addendum sounds very much in the spirit of the Intersectionality Rider which another CNF group is working on, which includes a First Nations land acknowledgment, labeling of bathrooms, and pronoun usage amongst other items. The self-education rider or the intersectionality rider, once it is available, would be worth incorporating as addenda, as they are integral to reshaping our field and how we work together.

Green Touring

A producer shared how she now includes a carbon offset fee in her list of deliverables if the artists are flying and purchasing their flights. Although this is a new practice, she hopes that as this line item is included in artist and presenter budgets for grant reporting, eventually more and more institutions will make the responsible decision to begin replicating those budgets. Another manager noted that he has been sharing the green rider from Julie’s Bicycle to encourage his artists to adapt their technical and hospitality riders to be more environmentally aware.

Focus Group

Artists

Focus Group

Technicians & Designers

Focus Group

Presenters

Focus Group

Agents, Managers & Producers

Conclusion

As mentioned above, equitable contracting is a constantly evolving process, and one filled with tensions as we seek to ensure legal protections while maintaining the tone of partnership. We offer these documents to all values-aligned thinkers and workers in our field who may find them useful as templates, guidelines, or educational tools. We invite folks to use them as examples for reference and discussion as one-size-fits-all will not work for artists, managers, and organizations. Looking toward further work on equitable contracting in the field, one clear priority is to flesh out best practices in accessibility. As we look forward, questions also arise: How do we get field buy-in for an equity-driven contract? Do we invite a running list of presenters to sign on to the document and its principles or take another approach? And what role do funders play in this conversation? We know we need funders at the table for this contracting conversation and broader conversations about equity and justice in the field; how do we get them engaged?

While we aim to offer a practical contractual document for the field from a place of justice and transparency, there is much value in the learnings, relationship building and conversation we're having around this topic. Coming together from our multiple roles in the field is both a challenge and a benefit to the process, as we mention in the intro of this article. As organizing around equitable contracting continues, it is important that a wide range of voices and identities are present in the process. Moving forward, this working group and aligned efforts in our field must continue organizing across identities to center Black, Indigenous, and disabled people, and those with other identities that have been historically disenfranchised in our field and our country.

This is about more than just building a contract. Efforts across our field are supporting each other in building a more collaborative and equitable culture. In closing, we would like to uplift the work of parallel efforts looking toward ethical contracting and partnerships in the performing arts field:

- The Association of Performing Arts Professionals (APAP), “Building Ethical and Equitable Partnerships (BEEP) in the Performing Arts"

- Creating New Futures Phase 1 Document: Working Guidelines for Ethics & Equity in Presenting Dance & Performance

- Creating New Futures Phase 2 Document: Notes for Equitable Funding

- Creating New Futures Instagram Live Conversations: Notes for Equitable Funding from Arts Workers

- Dance Artists National Collective (DANC)

- Dance/USA, “Contracting Resources”

- We See You WAT

- Working Artists and the Greater Economy (W.A.G.E.)

About the Creating New Futures Contracts Working Group

Sandy Garcia (she/her) is Director of Booking at Pentacle.

Ben Levine (he/they) is an interdisciplinary artist and designer and the Director of Production at Dance Place. Learn more about their work at extremelengths.org and benlevinedesign.com.

Sarah Lewitus (she/her) is the Program Officer, Performing Arts & Accessibility Coordinator at the Mid Atlantic Arts Foundation.

Hope Mohr (she/her) is an artist and attorney working at the intersection of the arts and social change. Learn more about her work at movementlaw.net and hopemohr.org.