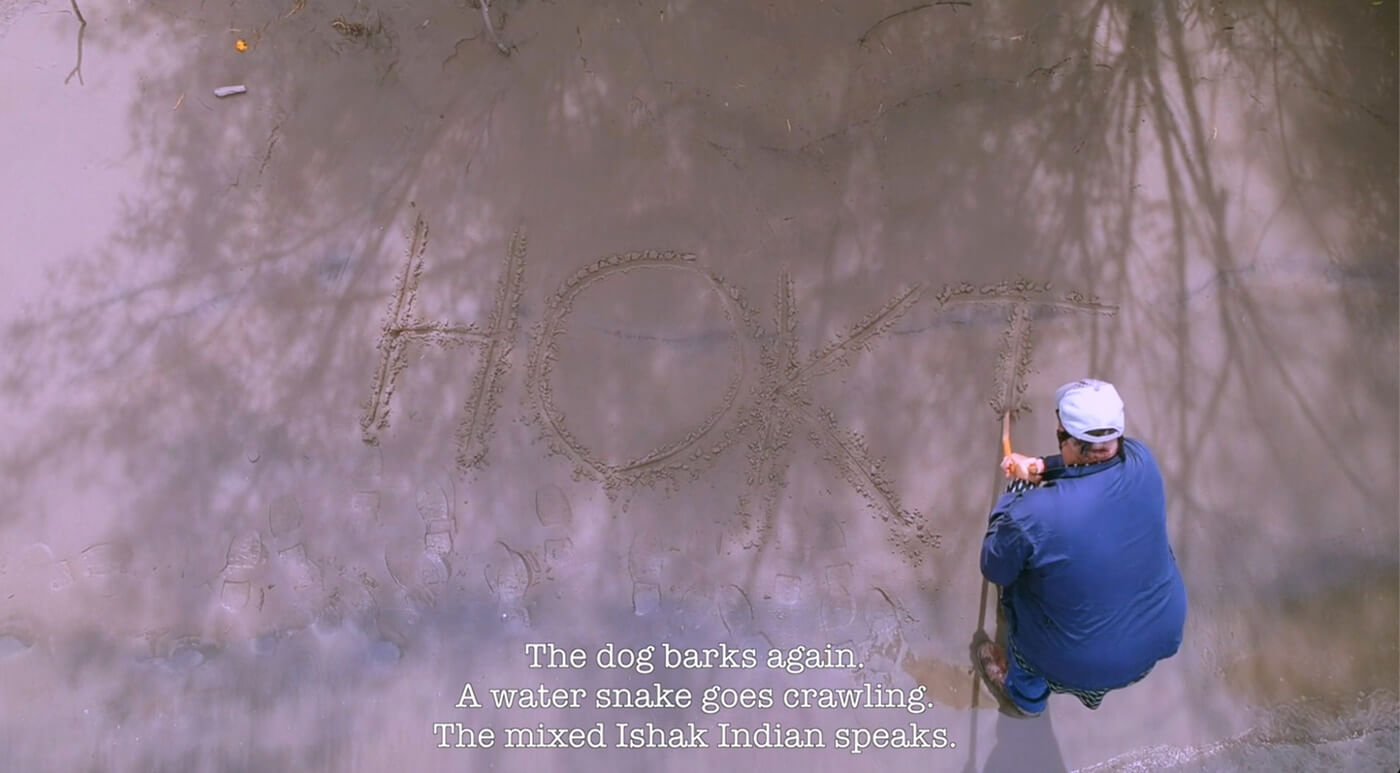

Hoktiwe: The First Film in Ishakkoy

Two Poems by

Jeffery U. Darensbourg

• 6 minute read

Fernando López and I made this film in 2020, a film which in some ways took us about six weeks to make, and in some ways took me three years to make. It is a short film, under seven minutes, but with a much longer story. It is the first-ever film in its language.

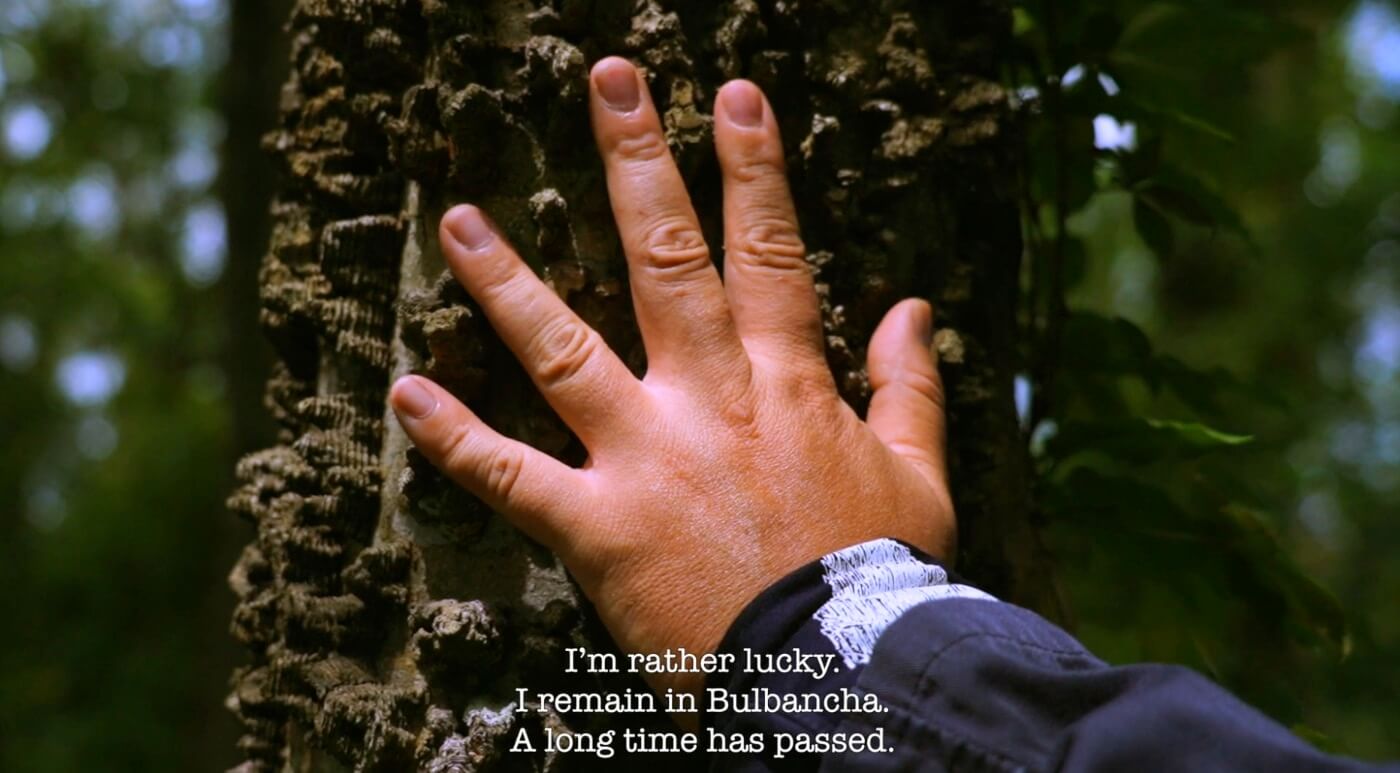

I have published both poems from the film in Indigenous journals, “Hoktiwe” in Transmotion and “A Studio in the Woods” in Yellow Medicine Review. I have also written a short introduction to the film for an academic journal. The comments here are based on an introduction to the film given as part of the 2021 South Summit, an event put on by New Orleans Film Society here in the city I call Bulbancha, where I live.

I am a member and tribal councilperson of the Atakapa-Ishak Nation, a historically important but non–federally recognized Indigenous Nation of Southwest Louisiana and Southeast Texas. That lack of federal recognition is a common feature of Louisiana’s First Nations for many reasons involving the unique history of race relations in this state. With that being said, the Ishak—“those who have been born,” “the human beings,” our own name for ourselves—continue to exist and thrive.

In 2018, after years and years of half-hearted efforts, I started trying to learn Ishakkoy, a language previously and incorrectly known by researchers as “Atakapan,” a name that reflects accusations of cannibalism against us. The Choctaw hattak apa means “maneater,” but likely refers to our habit of enslaving enemies taken in combat, not to actually eating people. As a deep Louisianan, I will eat many things the general American public will not consider, so there would be no shame here, I reckon. Still, we simply didn’t eat people.

The thing is, Ishakkoy is somewhat dormant, though it is not as sleepy as it once was. We do not know when the last speakers of the language from direct transmission walked on, but asking lots of Ishak People at gatherings has led me to believe it was sometime in the 1970s. It is difficult to learn a language in those circumstances, but fortunately we have a newly revised dictionary to help based on work done on our language by the Bureau of American Ethnology a century ago. The linguist behind this revision, David V. Kaufman, has produced a work that corrects previous errors, updates the orthography, and presents the vocabulary in a way that is easier to use. He has also spearheaded some online efforts and has been a supportive person in tribal efforts with language revitalization.

Tedium Laudamus

Ishakkoy seems to have been used as a written language seldom if ever during its time of flourishing. At present, though, Ishakkoy words live mostly on the printed page. I have experience with learning language textually from my earlier education in Western liberal arts. As a youth I studied both Latin and Ancient Greek, and while both of these languages are much studied and used, both are learned mostly—I repeat, mostly—via the printed page, just like Ishakkoy. The major difference is that the Western classical heritage has left behind more textual material than any one person could ever read across a lifetime, whereas the corpus of Ishakkoy is very small indeed, consisting of a few example texts collected in Lake Charles, Louisiana, in the 1880s. A few ceremonial songs in Ishakkoy have been composed by my tribal cousin Tanner Menard, a poet and musician whose work and personhood I really admire. Their work in the language continues to inspire my own, even as our writings take on different themes and pathways. There are also some example sentences in the dictionary itself, which is where my own classical training entered into my Indigenous project.

A cento is a type of found poetry composed using lines from other works. Classical examples include remixes of Homer and Virgil. The first centos I produced, in the 1990s, were made up of lines taken from the index of a 1971 edition of The Collected Poems of A. E. Housman, who coincidentally was both a poet and classical scholar. With this in mind, I began copying out example sentences and notes from the Kaufman’s 2019 Atakapa Ishakkoy Dictionary onto hundreds of notecards with the idea of using these examples to compose poems. While an Adaptations Resident at Tulane University’s A Studio in the Woods in the Spring of 2020, I made a database of these cards to facilitate easier use.

Doing this was one of the most tedious processes of my life. It easily rivaled editing my PhD thesis or working through dense Soviet chess training manuals. I cannot count how many hours I spent on these cards, but they eventually bore fruit. Such is the way of many artistic endeavors. There is a flash of insight, followed by weeks of working toward the realization of one’s vision, weeks of the preparation-production-revision cycle.

One of the first poems I wrote this way was “Hoktiwe,” the second poem in the film. The word hoktiwe means “we are together,” something I thought about while isolated, and eventually quarantined, at A Studio in the Woods during that time. I read it publicly at A Studio in the Woods the day after I finished the first version, and was met with a good response. I would eventually revise it dozens of times before it got to its final form. This was a good way for me to begin learning Ishakkoy. In time I began composing my own Ishakkoy sentences, and the first poem of the film, “A Studio in the Woods,” was one of my first efforts in that regard. The tedium pays off, I find. The dull, plodding note-taking was the core of it. More than in any other work I’ve done, I learned the value of tedium by making poems in Ishakkoy.

Collabs and Comrades

George Scheer, executive director of the Contemporary Arts Center New Orleans, contacted me in the summer of 2020 and asked if I might be interested in contributing to their open-call exhibition Make America What America Must Become, whose title was taken from a James Baldwin essay. I am not much of a visual artist, even if I have produced some works and have been in art shows. I had the idea of making a film from some of my poems. I am not a filmmaker either, but I knew immediately whom I would ask to be a collaborator, namely, Fernando López, who has contributed photos to a zine I coedit. I have admired his work for a while, and so I approached him with the idea that he should make whatever film he wanted to make of the poems.

That is collaboration. Fernando was not my employee hired to film something. He was and is my comrade and collaborator. He was taken on not merely for his expertise, but also for his ideas. We worked out some ideas for shots, and filmed it at A Studio in the Woods, given that one of the poems refers to that place and both of the poems in the film were written there. The visuals are his. It is his film, as he was behind the camera or controlling the camera on a drone. He edited the visuals. The text and music are mine. We made it together. It is ours, and I liked working this way, with divisions of labor like that.

Fernando had the idea of making a sort of music video out of it. In addition to shots of me moseying about at A Studio in the Woods, he also filmed me recording the audio of the poems plus the music I had composed on guitar, thunder tube, and hand drum. Our recording engineer, James Whitten of HighTower Recording, showed great skill in making it as easy as possible for my ideas about the audio to be realized in the best recording experience I’ve had in decades.

As such, the first Ishakkoy film came into existence, and I continue to enjoy it. It played at the Contemporary Arts Center New Orleans for the duration of the exhibition. On my first visit to see the exhibition in person, George Scheer told me that the looping, somewhat unresolved, guitar lick of the film is an excellent metaphor regarding the struggles of our times. I have to agree.

About Jeffery U. Darensbourg

Writer, public speaker, researcher, zinemaker, and provocateur Jeffery U. Darensbourg, PhD, is member of the Atakapa-Ishak Nation of Southwest Louisiana and Southeast Texas. He is the founder and Editor-Who’s-not-a-Chief of Bulbancha Is Still a Place: Indigenous Culture from New Orleans. Recently a writer-in-residence at Tulane University’s A Studio in the Woods and a Monroe Fellow of New Orleans Center for the Gulf South at Tulane, Jeffery is working on a book length study of the Atakapa-Ishak of Southwest Louisiana.