Guest Post: Decolonizing Alaska

March 26, 2019 • 8 minute read

By Asia Freeman

Artistic Director, Bunnell Street Arts Center

Emily Johnson returns home to Alaska every year to spend time with her family during traditional times of subsistence harvest. During her stay, the Yup’ik artist makes time to share and collect stories that shape her work as a dancer, storyteller and Artistic Director of Catalyst. Here, at Bunnell Street Arts Center, she’s found a place where people have gathered for decades. Long before this was an arts center, it was a general store at the end of the road to the west.

Johnson is part of a brave new generation of artists that is leading Alaska’s cultural sector to become adaptive and resilient, placing equity alongside excellence through inspired, decolonizing approaches that force us to evolve. Their artistic works reflect deeper truths about who we are and how we support each other—in ways both necessary and challenging, Alaskans are shaped and forged by our environment, our shared history and each other.

Incubator of Alaska’s artistic innovators, Bunnell’s mission is to nurture and present innovative art of exceptional quality for diverse audiences. Through exhibitions, educational and touring programs, artists in residence and artists in schools Bunnell aims to reflect and connect diverse and disparate communities. Conversations, workshops and projects help Alaskans cultivate our identities and strengthen creative visions. Due to geographic and cultural isolation we have few opportunities to access educational art experiences that truly reflect Alaska’s racial and cultural diversity. This arts center has been a powerful force in shaping and connecting Alaska’s cultural landscape for twenty seven years.

Revering this land and its stories has shaped and transformed me and my work as a curator at Bunnell Street Arts Center. Here, we examine, engage, challenge, and celebrate Alaska’s artistic resources, questions and opportunities. Today, on the leading edge of climate change, Alaskans adapt to survive. In ways both necessary and challenging, we are shaped and forged by our environment and each other. For Bunnell, and for myself, a process of self-definition and transformation is happening in tandem with the decolonizing methods of the artists we present.

‘The history we always knew’

Bunnell is located by a place called Bishop’s Beach by the homesteaders, fox farmers and fisherman who began settling this area about 100 years ago. It’s situated on the borderland of the Kenai River’s Dena’ina and the Sugpiaq (Russian colonizers called them Alutiiq), who are based across Kachemak Bay. Here, an abundance of sea life has sustained rich cultures and attracted many pioneers.

In 1937, Maybelle and Arthur Berry erected the Inlet Trading Post, now home to Bunnell Street Arts Center, to serve these newcomers. The Inlet Trading Post was a kit general store, milled in Washington and unloaded on the beach from a steamship, probably ordered from Sears and Roebuck. At 32 by 64 feet, stocked with can goods from floor to ceiling, it was Homer’s first “big box” store.

That was the history we always knew. But long before it was called Bishop’s Beach, the Dena’ina people named this place Tuggeght. We learned this name from Johnson when she was Artist in Residence in 2016. Her project SHORE: Homer at Tuggeght subtly sparked Bunnell’s efforts to place equity and inclusion alongside excellence in every aspect of what we do.

Survival stories

As part of presenting SHORE, Bunnell and Catalyst joined Woodard Creek Coalition, a cross-sector partnership of community organizations situated in the Woodard Creek watershed, which bisects our town from the mountainside behind us to the beach in front of us. The coalition was created with the intention of daylighting the paved-over creek to mark its presence through paint and dance.

This project invited community stories that revealed the critical, leading role that the arts have in uplifting the intrinsic, age-old and evolving histories of this place. Through storytelling, feasting and dance, Johnson’s act of land acknowledgement taught us that right here—as in many other places—colonizers erased and suppressed history by taking Indigenous land and announcing new names. Through Johnson’s work, the power of land acknowledgement flows like hidden rivers beneath our feet.

Similarly, a play about this land has deeply affected how we tell our story. In 2017, Bunnell co-commissioned Ping Chong + Company to create ALAXSXA | ALASKA (uh-LUCK-shkuh), a theatrical piece that weaves puppetry, video, recorded interviews and yuraq (Yup’ik drum and dance) in a collage of striking contemporary and historical encounters between Alaska Native communities and newcomers in our state. Performers Ryan Conarro, Gary Upay’aq Beaver (Central Yup’ik) and puppeteer Justin Perkins reveal little-known histories—at times humorous, at times tragic—and juxtapose them against their own personal histories as “insider” and “outsider” in the Last Frontier.

ALAXSXA | ALASKA audiences experience intimate encounters with a multimedia performance as epic as the changing landscapes of Alaska. We reflect on dozens of stories that alternately illustrate and challenge our impressions of the Great Land. ALAXSXA | ALASKA acknowledges that this place is built of many stories, and the colonial narrative that begins with Russian conquest, or the sale of Alaska to the U.S., or Statehood, is as deeply ingrained as it is discriminatory, exclusive and privileged. For many, especially non-Native Alaskans, hearing stories of survival—from ice-fishing to snow machine repair at 40 below—reminds us that the accounts of those who have survived over 10,000 years are here for those who are paying attention, like vast landscapes under a blanket of snow.

The most powerful occasion of witnessing ALAXSXA | ALASKA’s impact was, for me, in the village of Nanwalek. This village is only 10 minutes away from my home by plane—just a hop, skip and a jump across Kachemak Bay, where I’ve lived most of my life. But I’d never been there. Maybe because it’s off the road system. ALAXSXA | ALASKA drew a packed audience at Nanwalek’s K-12 school. After viewing excerpts of the play with the entire village, Chief Kvasnikoff invited everyone to a talking circle, including very small children.

We heard many courageous and powerful survival stories from families that were fractured as kids were shipped off to boarding schools, where Native languages were violently suppressed, and the ensuing intergenerational trauma of alcoholism, shame and violence. It reminded me that the arts are poised to help Americans experience truth and reconciliation if we care to pay attention.

“Decolonization begins in how we meet each other,” Conarro said, “how we tell our stories.”

Challenging the narrative

The experience of presenting ALAXSXA | ALASKA and witnessing its effect on audiences and communities has shown me that Alaskans are ready to push away from the Great White Narrative toward truer stories. From a Creation Residency to two tours of Alaska (2017 and 2018), the piece has been game-changer, inspiring teachers, health-care providers, tribal leaders and youth to share their personal stories and challenge the narrative of Alaska that is taught in our schools.

Visual artists are taking up the cause, too. As the world’s attention shifts to the shrinking polar ice cap and the future of our planet, Alaska’s place in the world has moved from the fringe to the center. Widely considered a “resource state,” rich in extracts such as gold, fish, timber and oil, Alaska has been colonized for centuries by forces that divide and dominate this state’s identity.

Alaska’s art market has for decades reflected the colonization and repression that has defined the industrialization of Alaska—a stereotypical idea of Alaska featuring dog sleds and “Eskimos,” igloos and objects of native iconography often reproduced abroad. In reality, Alaska artists present expansive ideas of Alaskan culture and people in art that explores both endangered traditions and new constructs of identity. Alaska’s artists propose a confluence of indigenous and global materials, expanding and redefining the roles of tradition and technology to explore difficult territories and express new ways of being.

“I live a mixture of Western and indigenous culture,” Joel Isaak (Dena’ina – Kenai, Alaska) said. “I explore the freedom to exchange information and experiences. Decolonizing means embracing cultural reciprocity and working toward universal acceptance of human beings.”

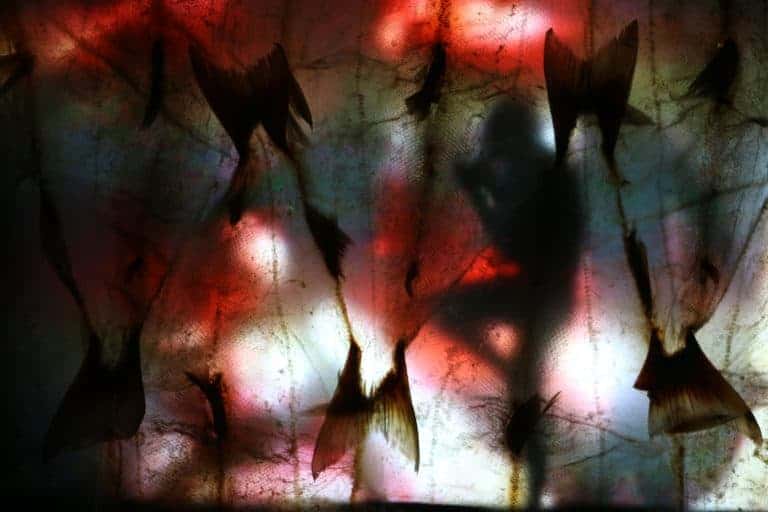

Isaak created a video installation, Łuqa’ ch’k’ezdelghayi “Visions of Summer,” in which his solo dance is projected on the back of a salmon skin screen. The installation is one of 31 artworks featured in Decolonizing Alaska, an exhibit produced by Bunnell that toured Alaska for three years and travelled to Washington D.C. In it, Alaska’s artists have been challenged and changed by the question: “How should we tell the stories of colonization?”

Artists respond, surfacing themes ranging from intergenerational trauma to resource management, and how the history of Alaska is told in our schools.For this exhibit, we embraced the challenge, and didn’t leave it to Alaskan Native artists. As a curator and visual artist, my feeling is that limiting the conversation to Indigenous artists only perpetuates colonization. Decolonization requires the concerted efforts and profound participation of both the colonizer and the colonized.

Reshaping traditions

The shared innovations, unconventional materials and respectful inquiry of Alaska’s working artists is beginning to dismantle a hierarchy of colonization and usher in a new era. In Alaska’s diverse artistic production, we see artist’s conversations connecting vast geographic distances and cultural experiences.

“I struggle with how many people draw boundaries and create categories about what kind of people and what kind of artists we are,” filmmaker Michael Walsh (Homer, Alaska) “I fear this perpetuates colonization.”

Walsh’s 35mm screen-printed film on celluloid celebrates the charismatic power of the Inupiaq woman rapper, AKU-MATU. “White man suppressed this power when he colonized Alaska, creating false divisions. I hope these divisions will dissolve in the 21st century and the voices of today’s leaders will resonate with the wisdom of our Indigenous ancestors and hopeful humans of the future,” he says.

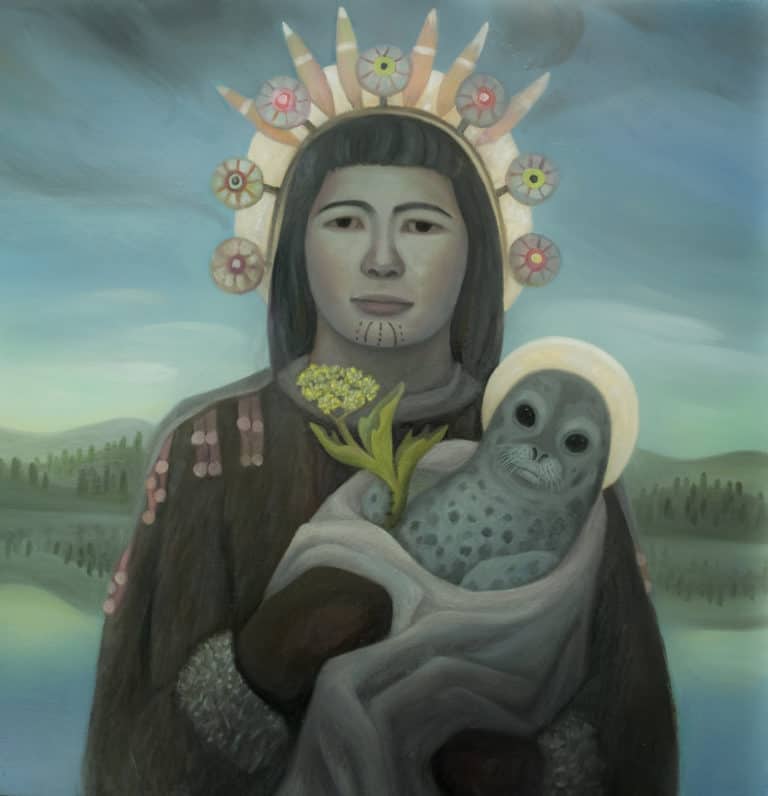

Artistic invention and imagination are reshaping traditions. New possibilities for cultural identity and sustainability are emerging in an environment of innovation. Linda Infante Lyons (Alutiiq – Anchorage) painted a portrait of her maternal grandmother from Kodiak Island in a bold, revisionist telling of history that elevates a new, powerful view of Indigenous women.

“Rediscovering culture and recovering lost religious icons are important steps in decolonization, “ Lyons said. “In my painting, St. Katherine of Karluk, I replace the symbolic elements of a Russian Orthodox icon with those of the Alutiiq people… I am a living example of the melding of two cultures, the native and the colonizer. In this effort to represent the decolonization of Alaska, I acknowledge the assimilated icons of the colonizer, yet bring forth, as equals, the spiritual symbols of my Native ancestors.”

I share these artists’ hopes that new images of power reflect deeper truths about who we are and how we support each other. May we heal centuries of racism, suppression and shaming. May new images of powerful Indigenous women infuse Alaska with resilience and respect.

Photos courtesy of Bunnell Street Arts Center.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Asia Freeman was born in Mexico and raised in Alaska. After graduating from Homer High School she attended Yale College (BA, ‘91) and Vermont School of Fine Arts (MFA ‘97). Asia is a visual artist, an adjunct art instructor for the University of Alaska and a co-founder of Bunnell Street Arts Center, where she holds the position of Artistic Director.