Who Would You Be:

Gesel Mason on Black Women and the Permission to Worry Less

By Gesel Mason

• 16 minute read

“Who would you be and what would you do if, as a Black woman, you had nothing to worry about?”

This question is at the core of choreographer Gesel Mason’s Yes, And, a new performance project that re-centers Black womanhood as the norm and operating force in the creative process. She asks herself and a Black sisterhood network of creative collaborators: “What would you create and how might you be in community with others? What emerges when I give myself permission to imagine or re-imagine another past, present, and future?” Yes, And is a process, or rather a methodology, of undoing and of freedom, the freedom to find and to be found from this recalibrated place.

Mason talked with NPN’s communications manager Sara Carminati about centering a project on community, rethinking traditional performance, and how embodying a free-spirited character named Josephine is helping her answer these questions.

Sara Carminati: These are rough times, to say the least. What’s the last thing that made you smile or laugh?

Gesel Mason: My Yes, And sisterhood just had a Zoom call to close out the summer and decide whether we should keep it going for the fall. People said just knowing that the space was there was helpful, so we’re going to keep making and holding space. During our calls I ask, “What do you need, and what are you doing well?” And because everything is so up and down right now, people share where they’re at. We get a lot out of it, knowing we’re not alone or hearing words of wisdom. I always find myself jotting stuff down. We laugh and we kiki and we cry and we know we got each other. It’s all the things.

The group started meeting this summer. It was a COVID situation. A few of us gathered and we were like, “I didn’t know I needed this. How can we keep doing this?” So we expanded it. Most of the group came together through me, but I asked who else needed to be there, which added some new voices to the mix. It’s a real intergenerational group: my mom is a part of it—she’s in her seventies—as is one of my former students, who’s in her early twenties. People are coming from all different backgrounds.

It’s been important to me that folks self-identify as Black women and that the project include trans women, because of the ways they are often targeted. But I also want to blow up the idea of what it means to have a sisterhood. Folks who are nonbinary—all of the sudden are they just out?

I’m thinking about the ways it can connect us versus isolate us, and I’m still understanding what that means and what that looks like. I know what feels right, but how do you make something people can see themselves in even if they’re not a part of it, if they see themselves outside of that community? But I have to say, this is one of the first times that I’m not that concerned. Because in centering these voices, we invite people as witnesses, and you’re welcome to witness. Our center has to be super strong and clear about what it is we’re engaged in.

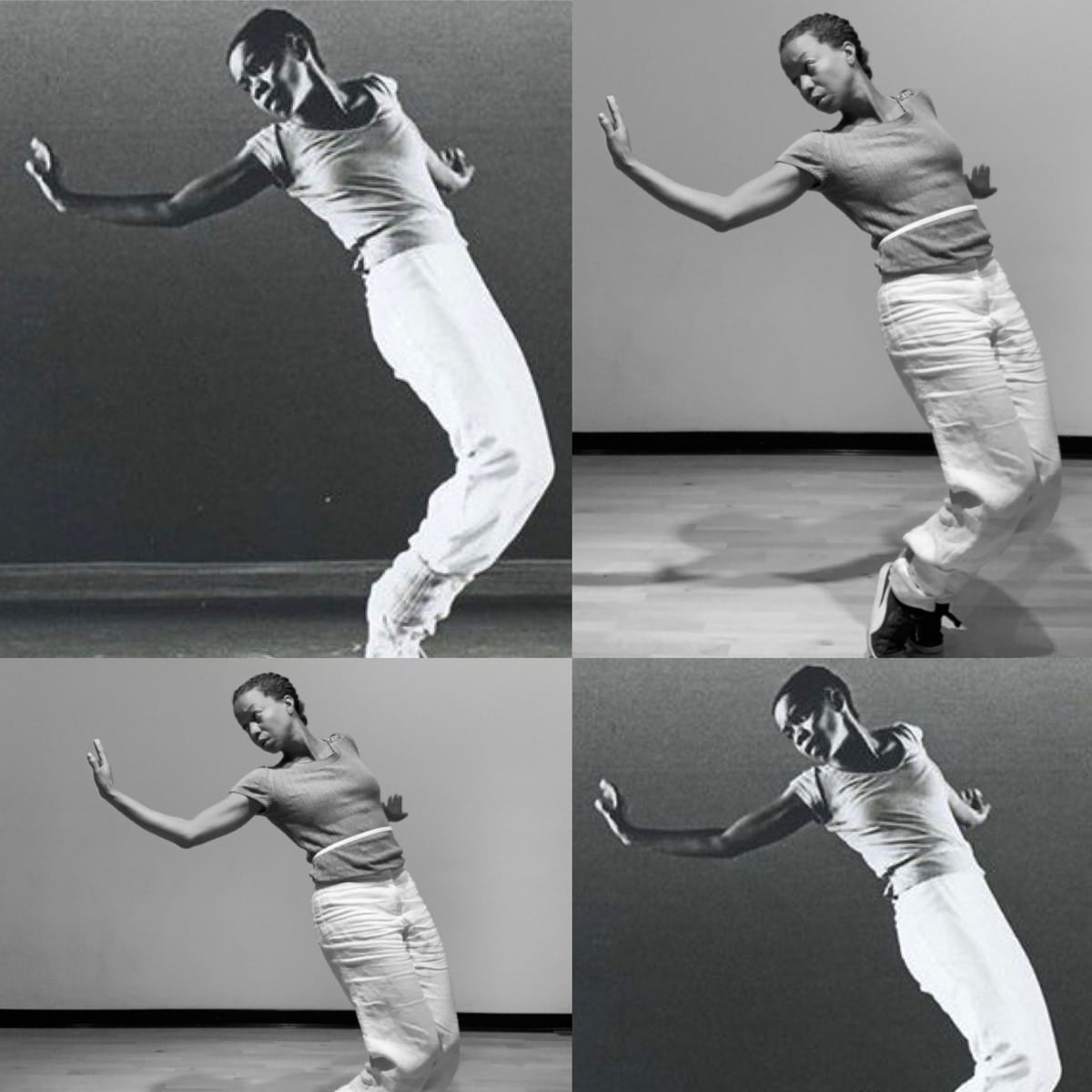

Photos: Josh Coe.

SC: Tell me about Yes, And. What is the project and how did it start?

GM: It had been floating around for a while as an idea and took root more recently. NPN’s support allowed it to be more than just an idea and allowed me to start imagining what it might be. You know how once your mind has an idea, every time you see it, you’re like—that. I felt like I kept seeing stories about how Black women and Black women’s voices are pushed to the side. Even with Black Lives Matter, sometimes we don’t think about its founders, who are Black women. I think Black women—and I’m totally generalizing here—have a tendency to hold space for others before themselves. They go, “It’s not about me, it’s about [gestures broadly] this. This is what needs to happen, so I will hold that space, I will take a back seat, I will support.” But when does that turn around? When do the tables turn? When are Black women being supported? When are they being centered?

And Black women are still so easily and quickly stereotyped. Serena Williams gets out there and is so quickly categorized as a certain type of Black woman. Even we fall into some of those things: “I’ve gotta be strong, I’ve gotta be there for so-and-so,” don’t put yourself first, don’t be boastful, don’t be all of these things. These boxes make you smaller and smaller, and you don’t even realize that you’ve totally contorted yourself in order to fit into something that doesn’t actually serve you. I was curious about how that was showing up for me, too.

I’m not sure when and how I landed on the question, “Who would you be and what would you do if, as a Black woman, you didn’t have anything to worry about?” But I realized it was an important question because every time I would ask Black women, their eyes would go wide, they’d be like, what?

Photos: Josh Coe.

I happened to ask that question to an upper-class white man, without the Black part, and he was like, “Well, I would have all the money in the world.” And I went, “Okay, this is not your question” [laughs]. Because after the reactions of Black women, I thought, “This is an important question.”

Residencies provided a big shift for the project. At Dance Place, during my Alan M. Kriegsman Residency, I brought in my collaborators, the folks I love to work with. I wanted to share the intuitive expertise of these women, that intuitive knowledge that you don’t have to translate. What happens if we get in a group and we start there?

There are carryovers from my work with women’s sexuality and my No Boundaries project. When I first started No Boundaries, I was thinking a lot about adding Black voices to the archive. And then I went, wait, what if they are the archive? Instead of, “Please add us to this archive,” what happens when we center Black choreographic voices? Then how does that open up other things? How does that shift how we see archives and performance? Part of that centering came from there.

I also did a project inspired by Audre Lorde’s Uses of the Erotic. She talked about the erotic as the “yes” within yourself, which has been coopted by the pornographic. Everybody has their own relationship to the erotic, that yes within yourself. Everybody has their own way that they get in. The group I worked with, we would talk about the pilot light that you can’t turn off. You know, in most spaces you can’t walk around like, “Heeey!” You just can’t, because it’s not safe. But when and where are the spaces, and how do we cultivate the spaces, where you can practice having that on at full blast? Where you can practice it being on at ten without somebody telling you it’s not right, it’s not okay, that’s nasty? And it was also thinking about what turns you on, which doesn’t have to be sexual. Where’s your passion? Both of those projects are underneath Yes, And.

When I found that question, that centered me. And at the Rauschenberg residency, I made myself a guinea pig. I thought, here’s a place where I can actually ask that question—they’re making my food, they’re giving me a stipend, I’m on the beach, I’m good. Let’s ask this question. I went there without any agenda except that question: Who would I be, what would I do, if I had nothing to worry about?

So I would leave my little cottage on the beach and walk right across to the dance studio, for five weeks. It was totally ridiculous. Sometimes I would go to the studio and answer some emails to free up my mind, and then I would listen to funk music, like Cameo. I noticed funk music was the only thing that was getting me on my feet, that would get me out of my seat. I started improvising and accessing stuff in my body from No Boundaries, from all of these choreographers that I’d worked with. “Oh, there’s a little Bebe in there, and there’s some Ralph Lemon, and here’s some Rennie Harris coming out.” I realized that all of these live in my body. I’ve done a lot of work around the body as archive. And I thought, so what’s after that? Who am I now? And I started taking pictures.

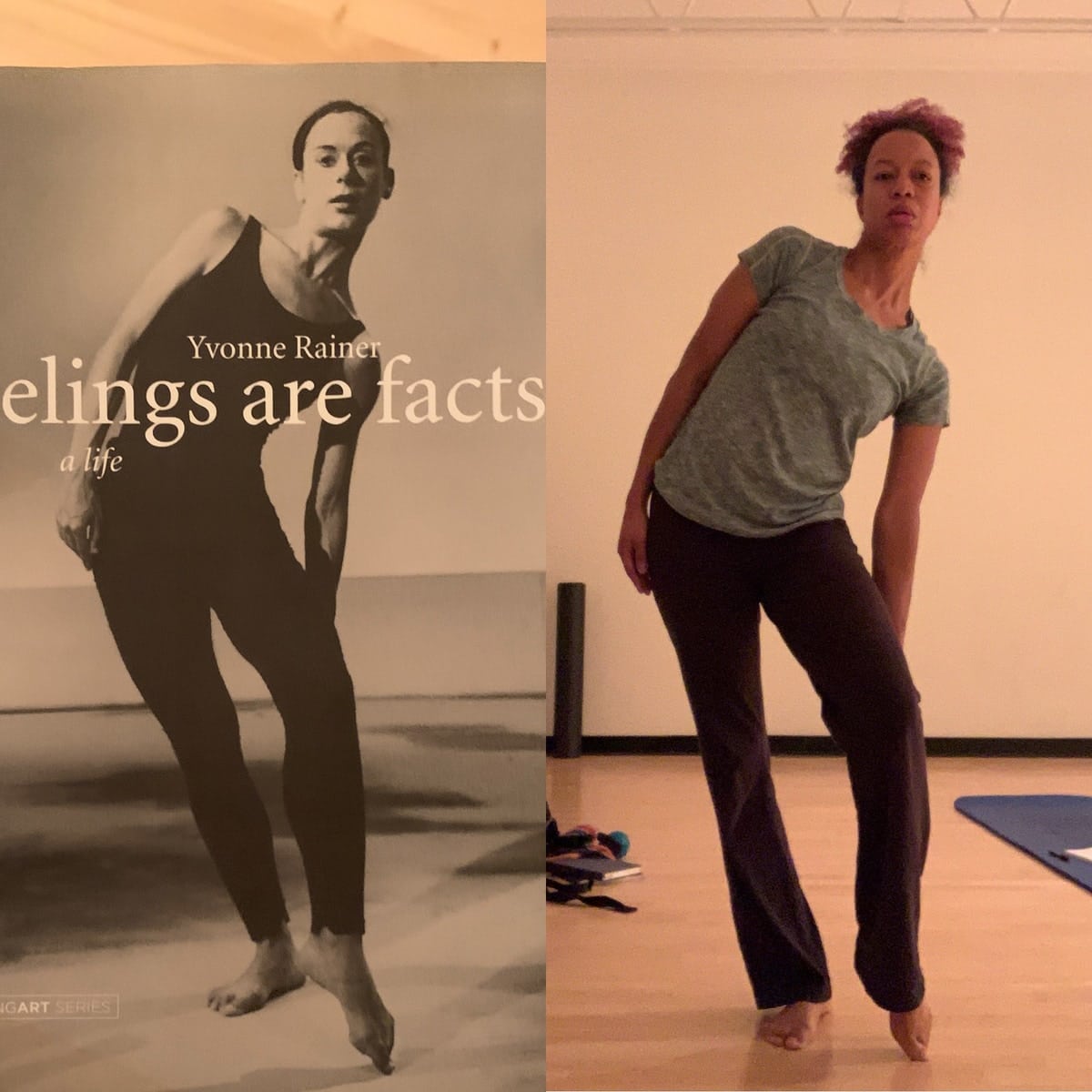

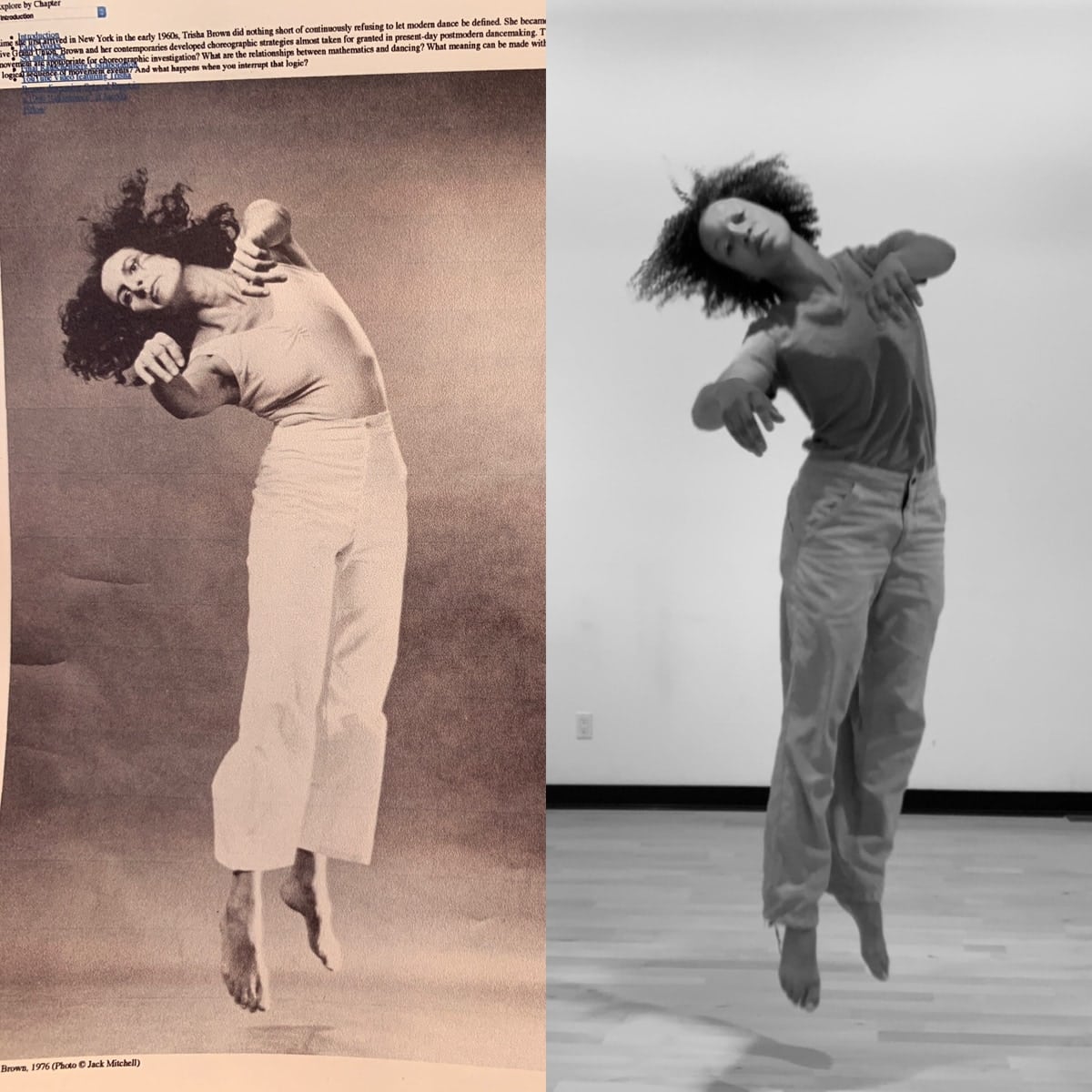

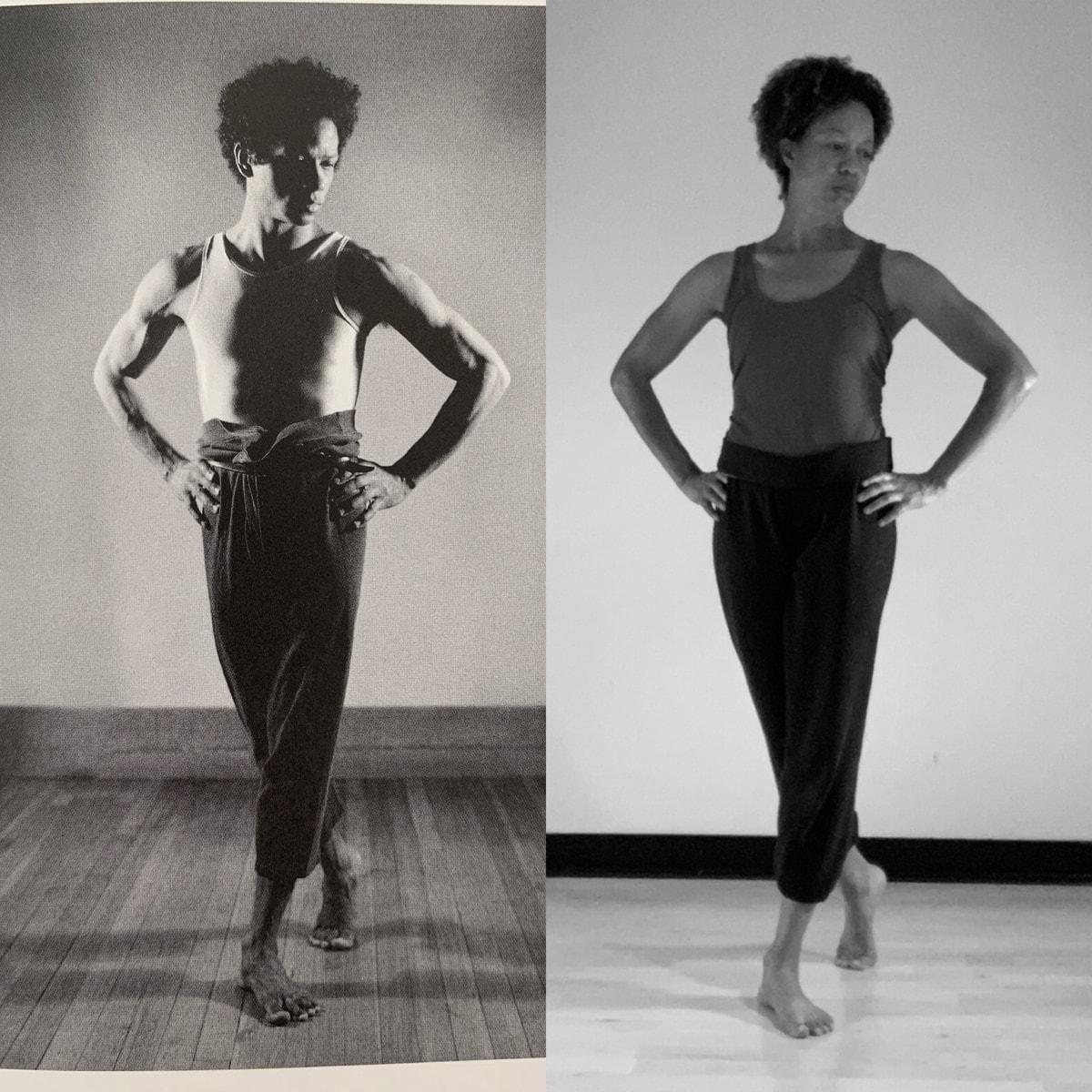

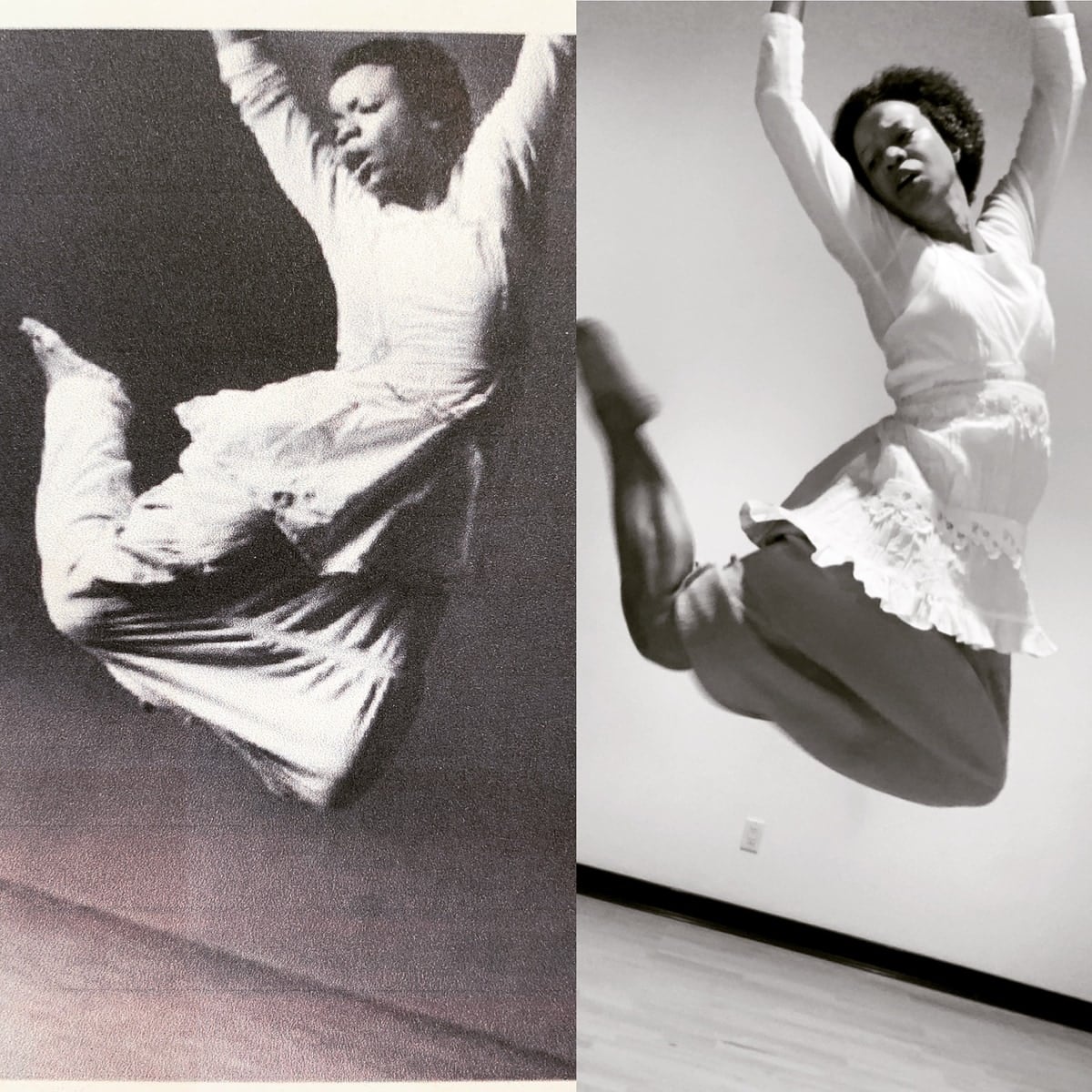

Robert Rauschenberg worked with a lot of dancers designing sets, so there were books in that studio. I started reading a Yvonne Rainer book while I was rolling out my IT band or something, and next thing I knew I was standing up striking one of her poses. I thought, I don’t know why, but okay. And I found Trisha Brown, who was also in the room. I started looking up Ishmael Houston-Jones and Ralph Lemon and Bebe Miller, old photos back in the day, and I tried so hard to do Pearl Primus, but I ruptured my Achilles and whoo! I used to have them jumps, too, man! I used to have those ups.

I started taking these pictures and putting myself side by side with these dancers. It became this solo practice, because it was just me and my phone. I would set up the picture, run in front of the mirror, for hours, and it became a thing.

Top row: (1) Yvonne Rainer and Gesel Mason. Photo: Gesel Mason. (2) Trisha Brown and Gesel Mason. Photo: Jack Mitchell, 1976. (3) Ishmael Houston-Jones and Gesel Mason. Photo: Pamela Moore, Danspace 1982. (4) Ralph Lemon and Gesel Mason. Photo: source unknown. Bottom row: (1) Blondell Cummings and Gesel Mason. Photo: Lois Greenfield, Jacob’s Pillow Archives, 1981. (2) Split-screen still of Bebe Miller’s Rain (1989) performed by Miller in 1989 and Mason in 2018. (3) Gesel Mason re-creates a photo of Miller during her residency with the Rauschenberg Foundation in 2018. Photo: Nat Tileston. Accompanying photos of Gesel Mason are courtesy of the artist.

So, I did that. I welded. And this is where Josephine starts to show up. The other people at the residency were a little like, “I don’t know what Gesel’s doing, but [chuckles] whatever.” We went fishing. One of the people there was set on capturing a rabbit. And he did—with a natural trap. All kinds of ridiculousness. I made coconut oil, and I burned it. Everything’s there, so I cracked a coconut. Something about self-sustenance was coming up: “I want to know how to do this.”

Gardening, turning compost, I mean everything. And with some of the other artists, I would say, I just want to see what you do. There was a sense of play. I was just following my intuition. If I wanted to go to the studio, I went to the studio. If I didn’t, I didn’t. If I wanted to walk on the beach, I walked on the beach. And I kept at bay the part that goes, “What are you doing? Are you taking advantage of this opportunity? Are you?” I just kept putting that away.

One day we went to a thrift store and there was this blue dress. A Grecian baby blue dress with rhinestones around the collar, size 16, chiffon; it was just so ridiculous. I thought “This dress is amazing. But I don’t have any use for this dress. I’m not getting this dress.”

I thought about that dress for a whole week. And because they didn’t really let us off the island very often, you had to plan if you wanted to go into town. Because I had started doing these photos I needed some of the costumes. I was using what I had, but I thought I needed a little something else. I went back and the dress was still there. And I was like, “I don’t know what it is, but I’m getting this dress.”

There was some carryover from another residency at Ragdale, where the group I was with went thrift store shopping, and I said, “Everybody, get what you want, get what makes you feel good.” I’m normally very practical with my clothes. With costumes I will go all out, but I won’t ever buy stuff for myself. I’m like, I just need some pants. We all bought these outfits and did a photoshoot. We were on their land, so again, this idea of sustenance. There we were—me, my mom, a poet, two hip hop artists. We just played; it felt like our land. I created a character at Ragdale who ended up with a name, too: Jasmine. But she didn’t end up as Jasmine until after Josephine.

(1) “Jasmine.” Photo: Jovan Landry. (2) Ragdale residency. Photo: Jovan Landry.

At Rauschenberg, I decided I wanted to do a photoshoot in this dress. We had support, people who were there to help us realize whatever we wanted to do, so I got to think bigger. I asked one of the staff, Josh [Coe], to do a photoshoot with me. He basically followed me around for a day, and that’s when Josephine was created. I said, “I don’t know who this is, but I think her name is Josephine.” He said, “Yeah, I like that.”

She just kept evolving and growing. I asked another staff member who was also documenting our processes, Leila, to videotape me. I wanted to create dance-for-camera shots. The beach goes right up to the forest, so I was in the forest and on the beach. I started improvising in the forest, and then I improvised on the sand. And that took me into the ocean. I rolled into the ocean in this dress. And embodying that character that way, I felt like this is what following my intuition and listening to my body led me to. I went to the post office in that dress. I got in the hot tub in that dress. I gardened in that dress. I got on a bike. Because Josephine doesn’t care. Josephine was out of time. Josephine would garden in that dress. I wouldn’t, but Josephine totally would.

That was a whole day, the photoshoot and the video. I went back full of sand and just got in the shower in the dress and started crying. I asked myself, “I’m not sad; what’s happening to my face? What’s this coming out of my eyes?” But I realized that what I was feeling was free.

And that made me cry even more. I thought, maybe this is the answer to the questions, “Who would you be, what would you do, if you had nothing to worry about? What would you make? How would you be in a community with others?” It felt like an undoing. But it required all that time. Josephine didn’t happen ‘til later, maybe the fourth week.

I was also learning to create cyanotype prints. Basically, you paint developing fluid and liquid on a piece of paper, you expose it, and whatever is exposed becomes blue, creating silhouettes. Rauschenberg used this process. I decided that I wanted to share these, the pictures, and everything I had, the shells I’d picked up, in a gallery space. I didn’t know what I was doing—we had a public showing, and I was making the thing up to the last second, because it was just coming to me as it was coming to me. I made a video of me rolling into the ocean. I made a video of me in the sand. I printed all of the photos at different sizes. I had my cyanotype prints, and I laid those on the ground. I found some paper, a foam-ish paper, and stuck it on the ceiling and hung it down, which became the foam of the ocean. And then there was the story—my roommate, the podcaster Eve Abrams, interviewed me. She interviewed Josephine.

“Josephine” installation by Gesel Mason. Footage shot by Leila Mesdaghi, edited by Gesel Mason. Sound design and narration by Eve Abrams.

Josephine seemed a little flighty. Eve wanted to know: How did you get to this land? Who are you? And some of those questions just weren’t so interesting to Josephine. But in her movement I noticed, she’s been through some stuff. But it doesn’t weigh her down. She had this very free spirit, but she’s got some depth.

I was interested in the fact that the place was called Captiva Island. It turns out it wasn’t about enslaved individuals. But I was curious about the slave trade around the Florida coast. I did some digging and found these slave narratives that were captured by the Federal Writers’ Project, which tried to capture some of these stories before these folks died. I looked up Florida, and there was a Josephine from Tampa, Florida, from 1937.

Josephine from Tampa, Florida, was not formerly enslaved, but she knew people who were. She told this story of the haints, the haunts, the spirits, and how when she was younger, she was “Rid by witches.” The person who captured her story captured it in her language, her voice, her dialect.

I didn’t think that I was Josephine. I wasn’t like: “I’m her.” But something felt conjured. In the story she says the happiest day of her life was her wedding day. And her wedding dress was blue, blue for true. Blue like the dress that called out to me at the thrift store. It still gives me goosebumps, actually.

It made me think about: What is beyond what we know and understand? What kind of other intelligence, intuition, expertise is there if we get out of the way? What can we access in our in our beings, in our creativity?

For the gallery showing, I decided that Josephine needed to make an appearance. I projected the videos on the big white walls. There was a recording of Eve reading key moments in the Florida slave trade, juxtaposed with her interview with me. So you’re hearing Josephine’s voice, and you’re hearing Eve reading this history. I put Josephine’s story up on the walls too, cut in pieces; it was the first time I’ve done anything like that. And it felt really empowering. It felt honest.

Sometimes as artists we’re in situations where you have to make something and it’s got to be good—or at least you feel like it’s got to be good—and that can really kill your creativity in ways that you don’t even necessarily know or understand. And to have that sort of unlock opened up for me what this could be. And then COVID happened.

I was already feeling unsure that Yes, And should be a performance in the traditional way. That’s something I’m pushing against—you get on stage and you want to sell tickets, you want it to sell out, and the critic is going to come. All of a sudden that felt really artificial. I’m trying to leave open how this project is supposed to exist, and COVID is giving me some permission. What if it’s not one event? What if it continues? What if I think of Yes, And as a methodology of undoing?

And in each location I go, I’m interested in working with the community. That’s different in every community. I want to find that center and center our voices and our questions and see what comes out of that instead of dictating what should happen. It makes it real slippery, and sometimes it’s hard to talk about because there isn’t a product. Instead, things emerge out of it. At Ragdale, we made a new hip hop song and I ended up using that song for a new piece at UT Austin. The song was called “Black Girl Magic.”

So these photos are part of the project. I think food is involved. I think there’s a kitchen. I think nature is a part of it, history, past, present, future, avatars, new imaginings about how we could show up in the future. But it’s all got to emanate from that center.

SC: If there’s not a product that’s the end of this, what drives you in this project?

GM: The community. The community, and the undoing. It’s when I see something come apart, and follow that line, and find something different. And to keep digging.

With these questions, childhood, Black girlhood, also came up, and that felt important. You see these beautiful young Black girls just being themselves, and then you see what happens. You see the rules come in—you’re too fast, you’re too sassy, you’re too loud, you’re too grown. These young girls are already expected to show up a certain way, and they get stripped of that childhood joy. The questions are in and of themselves keys that unlock a story, an image, a movement, a dance, an improvisation.

I’m creating methodologies and artifacts along the way, and I’m imagining a website that holds these. Because folks involved in the project have also said that knowing that somebody else is asking this question and has their back, knowing that somebody else is doing this work, gives them permission. That has been a huge word, permission. What do you need in order to have permission to follow that prompt? Somebody said, “Oh, if I knew other people were doing this, and they had my back? You couldn’t stop me.”

Something about it feels important for the community, the way people keep saying, I was grateful to know, even if I wasn’t there, that the space was there and I could come back whenever I wanted. So doing something is what feels important. That’s what keeps me curious and keeps me doing the work.

Photos: Josh Coe.

SC: What does Josephine allow you to be or to do?

GM: She feels like a conduit. Like I said, I would never walk around in a blue dress. There’s something bold about it. She was gardening, she got in the pool, she went fishing, all of that in the blue dress, right? She didn’t give a shit, and trying that on is pretty powerful. I think that’s where these avatars are coming from. Put on something you wouldn’t necessarily put on. Wear something you wouldn’t wear. Wear that lipstick. Give yourself . . . She gives permission, right?

This is similar to that work around the erotic. Once you taste it, once you know what it feels like, then maybe it’s something you can access again. It’s not just a concept; it becomes an embodied experience. And if you can hold on to that, maybe you can carve some other paths. It’s a type of permission that she gives.

I’m curious when and if she’s gonna show up again. I don’t know. Because she still feels very much here and present. There’s something about the way that she navigates time that feels important. I’m open to it and curious what else she has to share. I think she might have some thoughts about COVID. Or somebody else might come out of COVID. Like I said, I went back after Josephine and named the magenta character Jasmine. Jasmine was super playful, she felt younger than Josephine. I’m curious who or what might show up with enough space. I feel like this might be a sisterhood that I don’t know yet. And she may not show up. She may have done what she needed to do, but I’m curious.