Building Beauty

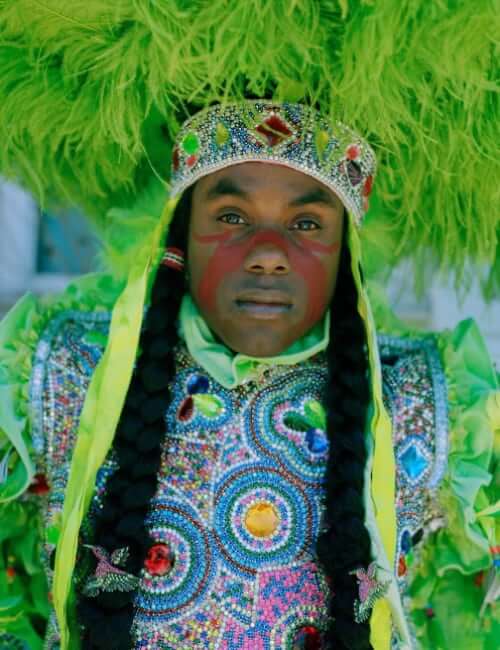

A reflection by Walter Sandifer III, Spy Boy Walter of the Beautiful Creole Apache

Adapted from an interview with Sara Carminati

• 10 minute read

“For me, being born into the Masking culture feels like God blessed me with the eye for building beauty.”

Here in the Masking culture of New Orleans, our expression of freedom comes from sewing and building suits made of thousands of rhinestones, beads, and feathers. Tribal members sew large and small stories and designs year-round to create their expressions of freedom for Mardi Gras Day, St. Joseph’s Night, and Super Sunday.

I was born into the culture. Luckily, my dad was doing it a few years before I was born, and he saw the power in being part of a tradition and learning the culture. He saw real meaning in it. Because people laid down their lives for our freedom. Masking is like going to church. The same way you go to church to source motivation for the week, that’s what Masking does. Masking is uplifting, it’s therapeutic, and it has a reason behind it.

There are three main parts to Masking culture.

The first part of Masking is understanding the people who came before you. Masking comes from Native Americans who were here in Louisiana, here in Mississippi, and from Africans and Haitians who came in on the Mississippi River. It came from the lifestyle that the Native Americans lived here on the river: how they farmed, how they sang songs, how they danced, how they commingled. And it came from the Haitians and the Africans: how they danced, how they lived, how they farmed, how they mingled with each other. The origins of this Masking culture are the Native American lifestyle and the African lifestyle. Our sewing style spirals down through the generations from the African craftwork of our ancestors. Our featherwork derives from our Native American ancestors who blessed us with the craft of feather dressing.

To really put what we’re doing into perspective—Where are you standing? Where in New Orleans are you located right now? Where you’re standing, where I’m standing, all this is Native American land. Anything that comes here on the Mississippi River is entering Native American land. To this day, we live on the river. Whether our people came from the Caribbean, or whether they came straight from Africa, wherever you were from, you had to earn some type of relationship with the people who were here before you. Life on the river.

So, the first part of Masking is understanding your background, whichever side you identify with, whether it be the African side of Masking or the Native American side. Knowing what kind of lifestyle the Americans lived, what kind of lifestyle the Africans lived, and why they had to live that way. Understanding who helped enrich the soil that we live on and giving thanks to the people who came before you.

The second part is surrounding yourself with people who can uplift you. Once you understand where you’re from, you want to put yourself in an environment with people who bring out the best in you and allow you to be comfortable to express yourself. Some people who mask like to sew pictures of the Native American lifestyle, some sew symbols from the African lifestyle. Some like to sew their religion or their family members. And you have people who like to just design. You want to put yourself around the people who will help you express yourself the way you want to.

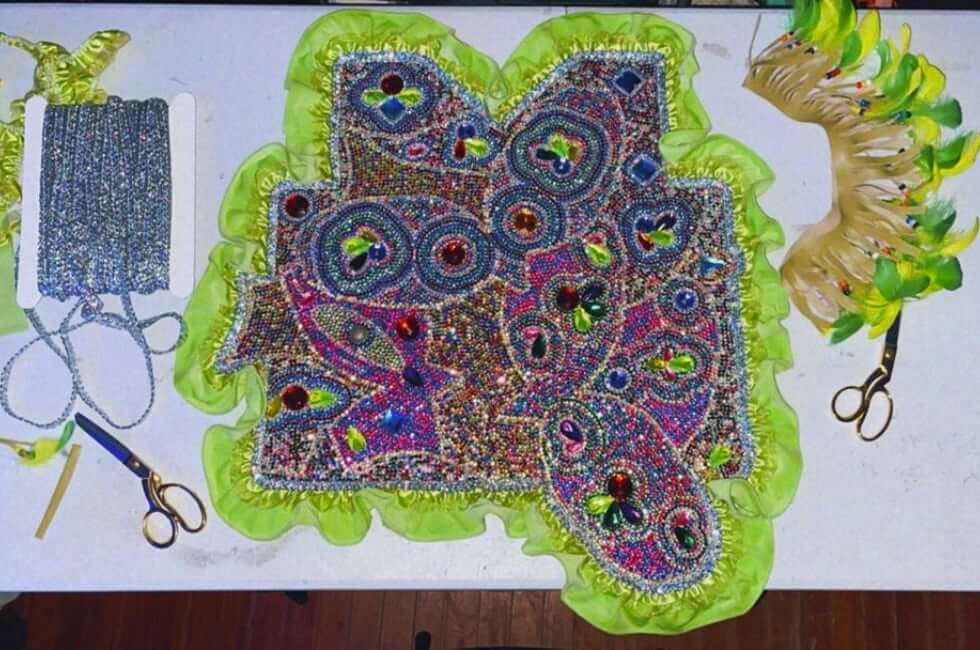

The third part of Masking is creating an idea for a suit. A suit is an art form that you wear. You create this art form from any combination of beads, rhinestones, sequins, canvas, glue, feathers, animal hide, bottle tops, buttons, ribbon, needle, thread, dental floss, wax, etc. Our suits normally take seven-plus months to create—finding new ideas, working to afford supplies, and spending long hours to sew and build the suits. It’s an artwork that you actually put on, and you craft it to fit only your body. Your glory isn’t given to anyone else—no one else can wear your suit. A suit is an art form expression that you create to fit yourself.

When I was a preteen, I was known in the nation for being the youngest to be putting his own suit together. I’ve been putting my suits together myself and taking pride in my work for some time. But I’m still an emerging artist to the world. I’m building right now. And I’m building strong.

When people see my suit, I want them to say, “Hold up. Look at his boots. I’ve never seen boots constructed like those. Hold up. Let me look at his war skirt. Let me look at the details. I’ve never seen anything like it. I’ve never seen it on the streets, as long as this culture’s been here. Wait. What does he have under that war skirt? Let me look at his shorts. Let me look at his vest, those designs, those patterns, I don’t know how he did it. He really cares about what he’s putting on his chest. Let me look at his stick, his protection, what he has in his hand. I’ve never seen anything like it. Hold up, let me look at his headpiece, let me look at his sun hat. He really put some work in.”

I created this hat. It didn’t come out the way I wanted it to, because when you create, you’ll always have things that you wish you had done better. But when I got outside, I felt great about this hat. It protects me from the sun, it’s light on my head, and it’s also full. And it felt good to know that I was the only Indian on the streets with that style of hat—the only one.

I joined this beautiful institution in New Orleans called Material Institute. I met this lady named Miss Norma who loves all kinds of different cultures from all over the world. When I showed her my suit she said, “I love this hat. It reminds me of something that they do in Cameroon.” I said, “No, I’m the only person in the world who’s made this hat.” She said, “Let me show you,” and pulled out a book, and in it was a Cameroonian tribe with a style of hat that was so similar to mine. I’d thought I was the only person in the world who’d created something like this, and in that moment, I realized that no matter where we are in the world we speak the same language, some way, somehow.

That moment with Miss Norma motivated me to continue to lock myself away and work for the expressions inside myself. I don’t try to borrow from other peoples’ designs. My suit comes from me. I use feathers in places they aren’t usually used and sew primarily rhinestones, in contrast to others. Don’t get me wrong, other people’s work is priceless. This world is filled with so many beautiful minds. It’s incredible what 6-year-olds can create, what 40-year-olds can create, what 20-year-olds can create. There is no limit no matter your age on the greatness of things you can create. I love all the beautiful art out in the world. And I want to be looked at that same way.

For me, being born into the Masking culture feels like God blessed me with the eye for building beauty. I was always taught to find my own identity through my expression in creating these elaborate designs. My lifestyle inspires my designs. My lifestyle of living in Holly Grove, living in New Orleans, and being from the 10th Ward of New Orleans, right on the river. When people see my suit, I want them to see my identity. I want people to see the hard work and dedication it takes to construct a suit, to sit down for hours a day and draw. I want people to see that I believed in myself, and I created this look from within. I’m motivated by my lifestyle and by working to be a great person. Being known as an established artist and culture bearer, somebody who does good for the community—that’s my motivation.

So, those are the three aspects of the culture: Understand where you’re from, put yourself around the right people, and then come up with your own ideas of expression.

Beyond these three aspects, there’s learning the dances and callings of the tradition of Masking. They must be passed down to you through someone, whether that be a family member or a friend who takes a liking to you. Most of the chants we sing and rhythms we play on tambourines, drums, and cowbells are carried down from generation to generation. The dancing comes from a mixture of African and Native American traditions. The drums are an African rhythm. A lot of people know it as Second Line rhythm, that old New Orleans, Caribbean feel that existed long before me and you. We’re just doing it in today’s time.

I live right here on the river, which is one of the most important water resources in America. There’s a war on water right now, and that’s what my next suit is about. Our people out in Michigan, in Mississippi, and there’s no telling how many other places, are going through a war with water in America that we don’t hear about. Our water is being polluted—it’s purposefully not being distributed to us in clean ways. The Mississippi River is not only a water resource; it helped us trade goods. With this suit, I’m giving thanks to water because without water we wouldn’t be alive, these houses wouldn’t be present, food wouldn’t be present.

For some reason, we humans just like to open shit up and throw it on the ground. I hate littering. It trashes up our environment, and then all this stuff goes into the water. When it rains, we wash this stuff down the basins and the basins take it out to the canals, the canals take it out to Lake Pontchartrain and the Mississippi River, and so on. I’m attaching my artwork to the water crisis and the environment. I want to design something that creates a talking point for the kids when they see me on Mardi Gras day. Every year there’s something new happening, and there is a moment to educate.

I create these suits because I’m in a war and people are in a war. People are fighting wars spiritually, emotionally, mentally, and physically—we all have things that we go through—so I’m fighting a war artistically. My art is therapeutic for the people who are fighting these mental, emotional, physical wars. It’s a resting space through the war. It gives people time to smile through the war, which is ironic because you don’t think of smiling through a war. For some people it heals them for that moment, and for some it’s something they will always have with them: “Man, I went to New Orleans and saw the Indians—they were singing and dancing and it was beautiful.” So, when they see me, I hope I make them happy, even if it’s just for five minutes of their year. I want my people to see me and feel better about themselves. I do it for them.

I taught for a year and a half in the ReNEW Therapeutic Program, working with students who had a more difficult time in regular classroom environments than the average kid. As its name says, it’s a therapeutic program. And what they loved most was the drumming side of the culture: beating on the drums and hearing the music, when you can be loud and it’s comfortable to be loud—it’s therapeutic to express yourself like that. I’ve also taught sewing at the International School of Louisiana, teaching the kids how to create what we create. There are specific qualifications to be involved in Masking, but creating art is worldwide. With what I can teach you how to create, who knows what a person may go on to create?

Masking was meant to serve the city of New Orleans and Louisiana. It was meant to last a long time: it was created to last in our neighborhoods for hundreds of years. It educates, it supplies financial freedom, and it uplifts New Orleans as a whole. It represents the bravery and truthfulness of who we are as human beings from Southern Louisiana. Masking is still serving its purpose. Masking still exists in the neighborhoods because it was created for a good purpose, and when things are created for good purposes, they usually last longer than those created for bad purposes.

It’s a very humbling experience to teach the younger generations. It makes me grateful that I was exposed to tradition and culture as a baby, because I don’t feel lost. As a grown man, I don’t feel lost. I feel like I have a sense of where I come from. I understand that my people were meant to be great, that my people fought for a greater future for me. We’re building the next generation to have pride about what we do here in New Orleans. We build for our younger generations to say, “Oh, we have greatness right here in our city. It’s right here next door to us.”

About Spy Boy Walter

Spy Boy Walter Sandifer III of the Beautiful Creole Apache is a second-generation Masking Indian born into the Creole Wild West tribe in 1996. His father, Walter Sandifer Jr., also known as Big Chief Beautiful, masked as a Spy Boy for the Creole Wild West for over 20 years and introduced Walter to the sewing techniques when he was 11 years old. He has been turning heads and dropping jaws with his unique art sense and singing skills ever since. Spy Boy Walter has performed onstage at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival numerous times, holds beading classes for youth, and teaches Masking drumming rhythms in local schools to preserve the unique culture and tradition of New Orleans, Louisiana. He is a young entrepreneur, a family man, and the owner and operator of Tribal Pro Moving.